Derniers numéros

I | N° 1 | 2021

I | N° 2 | 2021

II | N° 3 | 2022

II | Nº 4 | 2022

III | Nº 5 | 2023

III | Nº 6 | 2023

IV | Nº 7 | 2024

IV | Nº 8 | 2024

V | Nº 9 | 2025

> Tous les numéros

Supplément au dossier « Aspects sémiotiques du changement »

|

Change : modulation and modularity. Simon Smith

Publié en ligne le 31 août 2025

|

|

|

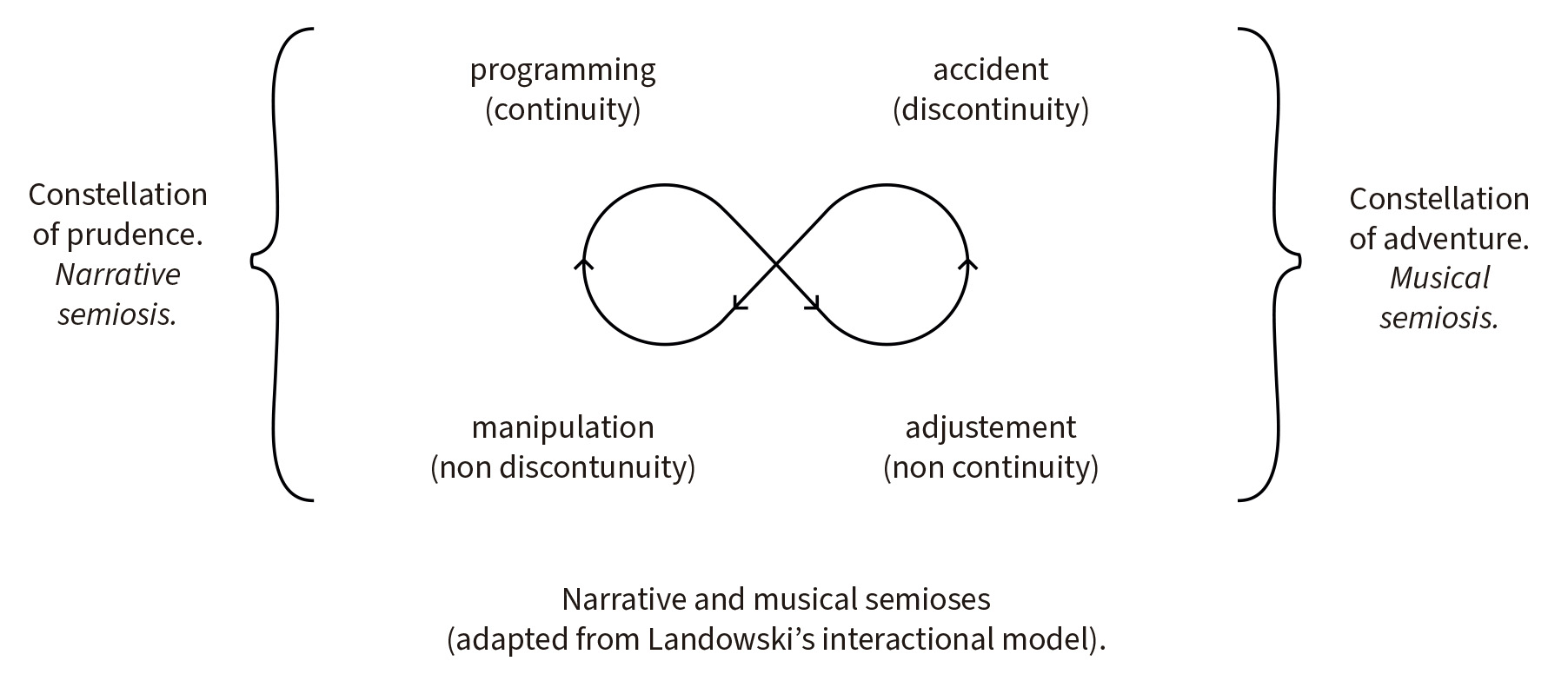

The aim of the following lines is to introduce the notion of musical semiosis as a counterpart to what I shall call “narrative” semiosis. I do not, however, situate this work within musical semiotics1. Instead, its chief theoretical grounding is socio-semiotics, more precisely the semiotics of sentient experience pioneered by E. Landowski. The model he elaborated extends the scope of classical Greimasian narrative grammar by insisting that within intersubjective interaction meaning may emerge from the simple, ongoing, dynamic co-presence of two sensitive beings according to a logic of “union”, without any transmission of objects (which was formerly viewed as a necessary condition according to the standard logic of “junction”)2. This new semiotic model adds the regime of accident, based on chance, and that of adjustment, based on sensitivity, to those of manipulation (based on intentionality and classically privileged) and of programming (based on regularity). Combining these four regimes of meaning and interaction, it distinguishes two sensemaking pathways that interconnect them3. Under the heading “constellation of prudence”, the first pathway, which connects manipulation and programming, sticks to the principles of classical narrative semiosis. The other one, connecting adjustment and accident under the heading “constellation of adventure”, provides the elements of another form of semiosis — a musical semiosis.

Each pathway starts from a regime characterised by an absence of meaning that actors are striving to fill : either the insignificance of the programming regime (the reproduction of continuity according to laws or programmes) or the non-sense of the regime of accident (the absurdity of pure, random discontinuity). These two pathways presume, in effect, that we give and make interactive sense and generate inducements to action either by disordering things and their relations (negating continuity) or by (re)creating order among them (negating discontinuity). |

* This work was supported by the NPO “Systemic Risk Institute” under Grant LX22NPO5101, part of Programme EXCELES (Czech Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports), funded by the European Union’s NextGenerationEU programme. 1 See E. Tarasti, “Musical Semiotics : a Discipline, its History and Theories”, Recherches Sémiotiques / Semiotic Inquiry, 36, 3, 2016 ; id., “An Essay on Rhythm”, Acta Semiotica, II, 3, 2022. 2 E. Landowski, Passions sans nom, Paris, P.U.F., 2004 (“Jonction vs Union”, pp. 57-66). 3 Les interactions risquées, Limoges, Pulim, 2005, p. 72. |

|

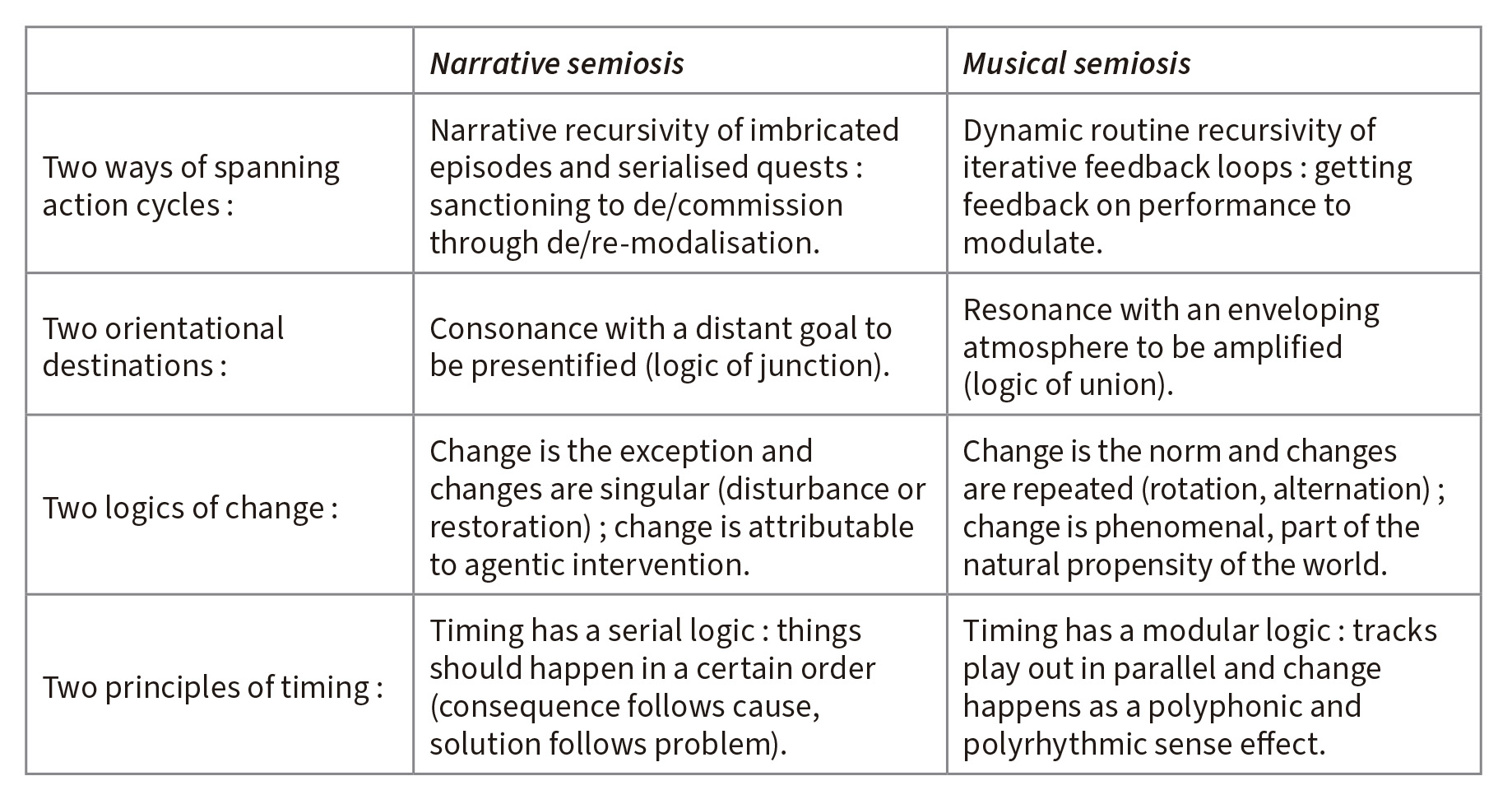

And each of them engages a specific world-view. I use this hyphenated form4 to denote what Greimas called une vision du monde : “a vision of the world implied both by significations and their conditions”5. If a world-view is a “syntactical game” (ibid.), “a reading grid of a structural kind (…), a generally-applicable principle according to which the world organises itself before our eyes”6, it applies perfectly to the distinction I draw between narrative and musical perspectives. Each perspective is a screen, lens or filter that makes the world appear as a “petit spectacle”7 with a characteristic actantial structure and a determined logic of interaction — and, I would add, a temporal architecture. The world takes form and makes sense as one kind of “spectacle” if we run our ideas, thoughts and feelings through narratives and another kind if we run them through music. The interesting specificity of the interactional model is that it articulates them to one another in a unified, coherent and dynamic system. Taking a lead from Juan Miranda Medina’s adaptation of this model8 — an adaptation which incorporates the musical notions of rhythm and modulation — I use the term musical semiosis to describe Landowski’s second sensemaking pathway, that of “adventure” founded on sensitivity and/or chance. Of course, the problematic of musical semiosis can be applied to understand how music itself affects us, but it can also be used more extensively, based on the assumption that people “listen” to the world as music9 and use this capacity as a sensemaking tool. Music was already one example (along with dance and rhyming poetry) evoked by Landowski to illustrate adjustment, but the connection is further elaborated by Miranda, who adopts, as a synonym for adjustment, the musical term modulation, a term also already used, as opposed to modalisation, by Landowski10 : To go on [durer] is always to modulate one’s own being, as stars, foliage or water do, on a plastic level, by means of their shimmering [scintillement].11 Adjustment consists in entering into harmony with things through their modulations, allowing oneself to be set in motion by them. Modulation can be defined as a process involving repetition combined with modification : an exterior element is introduced, which consistently alters a rhythm to yield a different rhythmic pattern12. Like rhyming poetry, modulation re-presentifies a previous micro-moment in a manner that makes what came before and what might come after ingress into an ongoing event and recursively affect its perception. Every modulation produces a change of perspective and atmosphere — a re-hearing. In a play on words, we could say that a pattern modulates where repetition meets répétition, which in French also means rehearsal. We perceive rhythmic patterns differently when elements get added or subtracted (like when a new instrument joins in a groove), and after a series of modulations we begin to imagine potential additions and subtractions. Miranda’s objective was to answer the question : “What happens after sanction ?”13. For sanctions do not necessarily decommission further action. This is what happens in the fairytales analysed by Propp, whose protagonists “live happily ever after”. But life is an ongoing series of tests, organised in “feedback loops”14 or “recursively related action cycles”15. Distinguishing between different types of sanction is key to understanding how action cycles are looped (or interrupted) by presentifying expectations relative to the next action cycle. Those that decommission (like in fairytales) consecrate action as a singular event. Those that commission generate new tasks which someone claims are the consequential implications of those just accomplished. Whereas Miranda attempts to build his insights from music theory onto the narrative schema, I draw a distinction : while narrative semiosis culminates with a sanctioning test which is generally oriented towards decommissioning (although it may, in some cases, commission a new cycle), musical semiosis culminates with “a comparison of the goal against the perceived performance” and a corresponding modulation16. Modulation also differs from what happens in stories when a hero fails and tries again. In narratives the goal, and hence also the way we measure success or progress, is fixed at the start of the process by whatever loss or disruption that initiated the quest. The hero, having failed a first time, might try a different tactic to achieve the same goal (that is to say the initially expected “conjunction”, according to narrative standard grammar), but there is always a convergent, goal-oriented processuality to narrative semiosis. From a narrative world-view, not only is change the exception to the rule (change is caused by an intervention that disturbs a state of affairs which would otherwise continue) ; so too, paradoxically, is repetition, for if change is exceptional, every change is unique. Afterwards, affairs will again “continue” — either in the original state (if change was successfully resisted) or in a new, but structurally identical state — until another intervention occurs. This is how a logic of junction conceives of duration and change17. On the contrary, according to the so-called logic of union, it is no longer tenable to assume that states of affairs last indefinitely in the absence of intervention. Instead, the assumption is that things are always in flux, becoming-other, moving and adjusting18. Hence, in what I call musical semiosis, “trying again” has a different connotation, one which is not given by reference to any desired end-state, any more than it could be given by reference to an initial state, since a state is just a snapshot of an evolving process at an arbitrary point in time ; just “a cut in the sonic flux”19. In musical semiosis, it is not only the tactic which needs to change when we “try again” : the goal20 is a moving target since the ongoing co-presence of two elements (a group and the music they are practising, a fan with a new album) will in itself cause a continual reevaluation of direction and destination. The goal is in fact a disappearing target, since the sense of direction presentified as music modulates is rapidly obsolete. It cannot last long beyond the moment when a feeling is potentialised as one “lands” in an atmosphere21, since how an atmosphere feels depends on the “angle of arrival”22. Put slightly differently, what music does — the sense we make of and the sense we make through music — depends greatly on sequentiality, at every level : the same chord will have different atmospheric effects depending on which chord it follows ; the same piece of music will make us feel differently depending on the nature of both the soundscape and the whole affective landscape (all the conditions that affect our mood and our receptivity) into which it penetrates. The term I therefore prefer for the orientation of musical semiosis is resonance. The dictionary definition of resonance is the vibration produced when a system is stimulated by sounds that adjust their frequency around (not at) the natural frequency of the system. It emphasises the constant variation implied by the logic of union, close to the principle of “regeneration by rotation” in classical Chinese culture where, as in music, tension and release call and regulate each other in a never-ending relay23. Helmut Rosa has likened resonance to the experience of listening again to a favourite piece of music and hearing it differently24. The point of reference for resonant sensemaking is an ephemeral, enveloping, present atmosphere, not the fixed, distant (i.e. absent) goal with which one strives for consonance in the logic of junction. Unlike the “states” of narrative semiotics, atmospheres cannot last. But they may linger, impregnated as they are “by past memories and future anticipations”25, and we all know ways of lingering in them (which often involve music in one way or another). Atmospheres are processual, so they can be prolonged and amplified by resonating with them. But, unlike states, they remain in constant metamorphic motion. The movement, ongoingness or onflow of a musical process (or any process “thought musically”) billows around an axis like a rising air current, and hence at any one time could be divergent or convergent26. This is why I insist that, while music can produce strong feelings of goal-orientation (particularly in the Western tonal tradition, where the pull of the tonic is a key compositional principle), a musical logic of change is not intrinsically goal-oriented. The audible sense one often has that a piece of music is heading towards a finale is a “downstream” choice that depends on how a composer constructs the music’s temporal architecture or how listeners attend to music (music theorists distinguish between “future-oriented attending” and “analytic attending” where the focus is on “local detail (…) over relatively short time periods”27). The more fundamental “upstream” choice, which I argue is intrinsic to a musical world-view, is an orientation towards (something like) the logic of union, with its key assumption that the rhythms — the “music-like temporal patterns” — of other interactants need to be taken into account28. This relational competence is an art of “anticipations and lags”29, of micromoving to maintain balance30 and of exercising the patience necessary to wait for a situation to ripen — and then act31. In other words, participants are condemned to be always only “getting used to” the dynamics of the process they are jointly participating in, as they go through it again and again. Writing about habit formation in Passions sans nom, Landowski explains that repetition (and répétition) constitutes a valuable and dynamic way of knowing the world : as habits form, “the accumulation of precedents modifies the value of each new occurrence”, which is why “far from depriving the object of its novelty, [habit] renews it from within as the very effect of adjustment between two living forces”32. In this sense, a semiotics of sentient experience is always also a semiotics of repeat performance, since its principle of interaction — a dispositional generosity (disponibilité) — depends on repeated listening and responding. Listening in this way (listening-responding) recalls Pierre Schaeffer’s “reduced” listening (i.e. listening to an object for its own sake). Reduced listening is only possible after unlearning the ability to use listening as a means of reading and decoding33 — unlearning what socio-semioticians might call “manipulative” listening, listening as a sentient competence “instrumentalised” for purposes of distinction34. Tellingly, Schaeffer made use of repetition in his auditory experiments to facilitate reduced listening, because he found that listening repeatedly to the same short sounds was the perfect “deconditioning” technique. By preventing the sounds from “pointing” to events or significations, repetition helped break conventional ways of perceiving the world and break in novel ones35. This im-mediate style of listening, a concrete manifestation of a semiotic experience nurtured by repeat performance, belongs to the repertoire of archetypal gestures associated with adjustment as a logic of action, in opposition to the “reading” gesture associated with narrative manipulation36. Where a “reader” of the world makes distinctions, a “listener” to the world (paying it a “symphonic attention”) hears everything at once37. Where a “reader” of the world hears (and is guided or interested by) stable significations, a “listener” to the world hears (and responds or adjusts to) shifting modulations38. To complete the proposed model of musical semiosis, I need to introduce a term that shares a lexical root with modulation : modularity. Also familiar in (especially electronic) music, it refers to the divisibility of a composite entity into “modules” which are the building blocks of polyphonic and polyrhythmic structures when overlain as multiple parts or “tracks” in a composition or its performance. Modules are typically switched on and off, or faded in and out, and in many musical genres modulation is closely linked to modularity : if the next repetition adds, takes away or alters the balance between modules, the modification of the sense effect stems from the piece’s changing modularity. But modularity also has unintended sense effects, since when multiple parts or tracks are overlain and play out “in parallel”, change is an immanent property of the dynamic polyphony and polyrhythmia between tracks. This represents a challenge to the way change is conceived when we follow a narrative sequence, or indeed listen to a single melodic sequence. There, change has a serial logic, in the sense that our sense of timing (our expectations about how things should develop, at what rate, when phases should begin and end, etc.) is guided by an assumption that one thing follows another. A modular logic overturns that assumption. To obtain a sense of timing we need to pay attention to the overlaps, interferences and synergies between several distinct sequential structures. I want to suggest that this requires similar competences to those found in the regime of adjustment. I draw here on the work of management scholar Stuart Albert, who argues that many timing problems in contemporary organisational life stem from our inability to abandon a logocentric bias that prevents us thinking in terms of modularity (my term, not his) : when we speak, we say one word after another (…) When we reason, we demand that our conclusions follow logically from what came before it. In short, we are serial creatures in a massively parallel world. As a result, we are continually “blindsided” by events that seem to come, to use a baseball analogy, “out of left field”. But a large part of the problem is that we have gotten the location of left field wrong. It is not left, but up. Many things are happening at the same time, and we can’t keep track of them.39 To manage these timing problems, Albert suggests a simple analytical method : give all “nouns” their own track. Whatever might have its own developmental sequence, its own rate of change, its own rhythm or punctuation, and so on gets its own track. Each of these has the potential to affect what is going on in your own situation.40 His analogy is with the different melodies on each horizontal line of a music score which, when recorded, become tracks on a mixing desk. Each melody is a sequence with serial constraints (things must happen in a certain order), like the succession of narrative states to which Greimas gives the name “syntagmatic junction”41. But multiple melodies can be playing at the same time, in parallel. The separate melodies are not different perspectives on the same events : there is no “paradigmatic junction” between them. They just intersect, reflecting how situations in which we find ourselves consist of innumerable “moving parts”, some of them powered by narrative programmes, but not ones that are joined by an underlying polemical structure. Events that take place on one track can interfere with events on another, but even if they do — even if the events on one track delay the completion of the events on another, for example — they can all eventually play out to a satisfying resolution. Or just keep on playing. In summary, we can contrast narrative and musical semiosis on four axes : the way they span action cycles, their orientation towards goals or atmospheres, their logic of change and their timing principles, as shown in the following table.

The theoretical and methodological propositions briefly sketched in this article are, to a large extent, just another version of the socio-semiotic interactional approach. What distinguishes them is only the musical inflection I have given to the pursuit of sentient experience. I argued that thinking musically means taking seriously the sense effects produced by repeat performance, which can become an important methodological technique as it opens interpretive gaps between repetitions and locates the observer in a cyclical rhythm of becoming. To quote a common musicians’ saying, the researcher or the subject performing musical semiosis is forever beginning again, trying to call forth those peculiar sense effects that can happen when we do things, like a group of musicians in rehearsal, one more time with feeling. Thinking about change from a musical world-view is also aided by noticing how musical patterns not only modulate as they repeat, but are often arranged in modules — tracks playing out in parallel — and the timing of modules (their inter-duration, we might say) has implications for how we experience change, since it undermines the serial logic of narrative semiosis. But, as I underlined from the start, musical semiosis is not relevant only for music. It concerns the forms of change in any domain. For instance, modulation — the metamorphic motion of resonating atmospheres — and modularity — the polyphonic musical score of multiple processes — have particular relevance for making sense of the passages between states (or atmospheres) of emergency and the “new normals” that follow, as when the Covid pandemic “ended”. In a forthcoming study, analysing this episode permits me to show how the above concepts help explain why and how an eclectic range of actors rejected the seemingly natural narrative conclusion that we can sanction the post-crisis delivery of an end-state by “moving on and forgetting”42. |

4 Without the hyphen, 5 A.J. Greimas, Sémantique structurale, Paris, Larousse, 1966, p. 117. 6 E. Landowski, “Une sémiotique à refaire ?”, Galaxia, 26, 2013, p. 31. 7 Sémantique structurale, op. cit., p. 117. 8 J.F. Miranda Medina, “From Continuity to Rhythm”, Acta Semiotica, II, 3, 2022. 9 Cf. E. Landowski, “Du sens musical de l’image”, Passions sans nom, op. cit., pp. 183-186 ; P.Aa. Brandt, “La petite machine de la musique”, Acta Semiotica, II, 3, 2022 ; R. Bocquillon, Sound Formations : Towards a Sociological Thinking-With Sounds, Bielefeld, transcript Verlag, 2022 ; L. Tatit, “Musicalisation de la sémiotique”, Actes Sémiotiques, 122, 2019 ; V. Estay Stange, Sens et musicalité, Paris, Garnier, 2014 ; P. Schaeffer, Traité des objets musicaux, Paris, Seuil, 1966. 10 Cf. Passions sans nom, op. cit., p. 46. 11 Ibid., p. 19 (our transl.). 12 “From Continuity to Rhythm”, art. cit., p. 93. 13 Cf. “From Continuity to Rhythm II. Adjustment and Entrainment”, Acta Semiotica, II, 4, 2022, p. 215. 14 Ibid., pp. 215, 224-5. 15 S. Smith, “What we meant by that was ‘let’s do this’. The interpretive metatext as pending account”, Actes Sémiotiques, 126, 2022. 16 “From Continuity to Rhythm II”, art. cit., p. 215. 17 Cf. E. Landowski, “Pourquoi le changement ?”, Acta Semiotica, III, 6, 2023, pp. 30-31. 18 Ibid., p. 31. 19 Sound Formations, op. cit., p. 170. 20 The term “goal” has little sense here, but I use it to respect Miranda’s definition of modulation (comparison of goal against performance to inform a modified repetition). 21 Cf. C. Preece et al., “Landing in affective atmospheres”, Marketing Theory, 22, 3, 2022. 22 Cf. S. Ahmed, The promise of happiness, Durham NC, Duke University Press, 2010. 23 Cf. F. Jullien, Nourrir sa vie. A l’écart du bonheur, Paris, Seuil, 2005. 24 C. Pépin and H. Rosa, “Comment entrer en résonance ?”, France Inter, 3 January 2024. See also H. Rosa, Resonance : A Sociology of Our Relationship to the World (2016), Cambridge, Polity, 2019. 25 C. Steadman and J. Coffin, “Consuming atmospheres. A journey through the past, present, and future of atmospheres in marketing”, in C. Steadman and J. Coffin (eds.), Consuming Atmospheres. Designing, Experiencing, and Researching Atmospheres in Consumption Spaces, Abingdon, Routledge, 2024, p. 8. 26 The spiral is perhaps the best spatial metaphor for this kind of processuality. Cf. E. Landowski, “Régimes d’espace”, Actes Sémiotiques, 113, 2010. 27 M.R. Jones, “Attending to musical events”, in M. R. Jones and S. Holleran (eds.), Cognitive bases of musical communication, Washington, American Psychological Association, 1992, p. 93. 28 As Jacques Fontanille wrote in his foreword to Les interactions risquées (op. cit.) : “The true value of the semiotics of interactions comes from the placement of the other, and of our interaction with the other, at the heart of the construction of meaning, right where tensive semiotics falls short, since it fails to go beyond (...) our sentient and cognitive relations with the world in general” (p. 4, our transl.). 29 Passions sans nom, op. cit., p. 176. 30 E. Manning, “Wondering the World Directly — or, How Movement Outruns the Subject”, Body & Society, 20, 2014, p. 171. 31 R. Chia, “Reflections : In Praise of Silent Transformation. Allowing Change Through ‘Letting Happen’”, Journal of Change Management, 14, 1, 2014 ; M. van Vuuren and B. Brummans, “Festina lente : Organizational Patience as Future-making Practice”, presented at European Group for Organizational Studies Colloquium, Cagliari, 6-8 July 2023. 32 Passions sans nom, op. cit., p. 157 (our transl.). 33 Traité des objets musicaux, op. cit., pp. 268, 342. 34 E. Landowski, “Le modèle interactionnel, version 2024”, Acta Semiotica, IV, 7, 2024, p. 122. 35 Traité des objets musicaux, op. cit., p. 478. 36 “Le modèle interactionnel...”, art. cit., p. 116. 37 Traité des objets musicaux, op. cit., pp. 332-3. 38 On this distinction applied to watching a film, see E. Landowski, “Unità del senso, pluralità di regimi”, in G. Marrone et al. (eds.), Narrazione ed esperienza, Rome, Meltemi, 2007. 39 S. Albert, When. The Art of Perfect Timing, San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 2013, pp. 20, 199-200. 40 Ibid., p. 205. 41 A.J. Greimas, Du sens II. Essais sémiotiques, Paris, Seuil, 1983, p. 34. 42 Cf. S. Smith, Switching Semiotic Styles during Health Emergencies : the Metachoices of Pandemic |

Bibliography Ahmed, Sara, The promise of happiness, Durham NC, Duke University Press, 2010. Albert, Stuart, When. The Art of Perfect Timing, San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 2013. Bocquillon, Rémy, Sound Formations : Towards a Sociological Thinking-With Sounds, Bielefeld, transcript Verlag, 2022. Brandt, Per Aage, “La petite machine de la musique”, Acta Semiotica, II, 3, 2022. Chia, Robert, “Reflections : In Praise of Silent Transformation – Allowing Change Through ‘Letting Happen’”, Journal of Change Management, 14, 1, 2014. Estay Stange, Verónica, Sens et musicalité, Paris, Classiques Garnier, 2014. Greimas, Algirdas J., Sémantique structurale. Recherche de méthode, Paris, Larousse, 1966. — Du sens II. Essais sémiotiques, Paris, Seuil, 1983. Jones, Mari Reiss, “Attending to musical events”, in M. R. Jones and S. Holleran (eds.), Cognitive bases of musical communication, Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 1992. Jullien, François, Nourrir sa vie. A l’écart du bonheur, Paris, Seuil, 2005. Landowski, Eric, Passions sans nom, Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 2004. — Les interactions risquées, Limoges, Presses Universitaires de Limoges, 2005. — “Unità del senso, pluralità di regimi”, in G. Marrone et al. (eds.), Narrazione ed esperienza, Rome, Meltemi, 2007. — “Régimes d’espace”, Actes Sémiotiques, 113, 2010. — “Une sémiotique à refaire ?”, Galáxia, 26, 2013. — “Pourquoi le changement ?”, Acta Semiotica, III, 6, 2023. — “Le modèle interactionnel, version 2024”, Acta Semiotica, IV, 7, 2024. Manning, Erin, “Wondering the World Directly – or, How Movement Outruns the Subject”, Body & Society, 20, 3-4, 2014. Miranda Medina, Juan Felipe, “From Continuity to Rhythm”, Acta Semiotica, II, 3, 2022. — “From Continuity to Rhythm II. Adjustment and Entrainment”, Acta Semiotica, II, 4, 2022. Pépin, Charles, and Hartmut Rosa, “Comment entrer en résonance?”, France Inter, 3 January 2024, https://www.radiofrance.fr/franceinter/podcasts/sous-le-soleil-de-platon/sous-le-soleil-de-platon-du-mercredi-03-janvier-2024-3111530 Preece, Chloe, Victoria Rodner and Pilar Rojas-Gaviria, “Landing in affective atmospheres”, Marketing Theory, 22, 3, 2022. Rosa, Hartmut, Resonance. A Sociology of Our Relationship to the World (2016), Cambridge, Polity, 2019. Schaeffer, Pierre, Traité des objets musicaux, Paris, Seuil, 1966. Smith, Simon, “What we meant by that was ‘let’s do this’. The interpretive metatext as pending account”, Actes Sémiotiques, 126, 2022. — Switching Semiotic Styles during Health Emergencies : the Metachoices of Pandemic Communication, London, Routledge, forthcoming (2025). Steadman, Chloe, and Jack Coffin, “Consuming atmospheres. A journey through the past, present, and future of atmospheres in marketing”, in ids. (eds.), Consuming Atmospheres. Designing, Experiencing, and Researching Atmospheres in Consumption Spaces, Abingdon, Routledge, 2024. Tarasti, Eero, “Musical Semiotics : a Discipline, its History and Theories, Past and Present”, Recherches Sémiotiques / Semiotic Inquiry, 36, 3, 2016. — “An Essay on Rhythm”, Acta Semiotica, II, 3, 2022. Tatit, Luiz, “Musicalisation de la sémiotique”, Actes Sémiotiques, 122, 2019. Vuuren, Mark van —, and Boris Brummans, “Festina lente : Organizational Patience as Future-making Practice”, presented at European Group for Organizational Studies Colloquium, Cagliari, 6-8 July 2023. |

|

______________ * This work was supported by the NPO “Systemic Risk Institute” under Grant LX22NPO5101, part of Programme EXCELES (Czech Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports), funded by the European Union’s NextGenerationEU programme. 1 See E. Tarasti, “Musical Semiotics : a Discipline, its History and Theories”, Recherches Sémiotiques / Semiotic Inquiry, 36, 3, 2016 ; id., “An Essay on Rhythm”, Acta Semiotica, II, 3, 2022. 2 E. Landowski, Passions sans nom, Paris, P.U.F., 2004 (“Jonction vs Union”, pp. 57-66). 3 Les interactions risquées, Limoges, Pulim, 2005, p. 72. 4 Without the hyphen, worldview has an unwanted politico-ideological sense. 5 A.J. Greimas, Sémantique structurale, Paris, Larousse, 1966, p. 117. 6 E. Landowski, “Une sémiotique à refaire ?”, Galaxia, 26, 2013, p. 31. 7 Sémantique structurale, op. cit., p. 117. 8 J.F. Miranda Medina, “From Continuity to Rhythm”, Acta Semiotica, II, 3, 2022. 9 Cf. E. Landowski, “Du sens musical de l’image”, Passions sans nom, op. cit., pp. 183-186 ; P.Aa. Brandt, “La petite machine de la musique”, Acta Semiotica, II, 3, 2022 ; R. Bocquillon, Sound Formations : Towards a Sociological Thinking-With Sounds, Bielefeld, transcript Verlag, 2022 ; L. Tatit, “Musicalisation de la sémiotique”, Actes Sémiotiques, 122, 2019 ; V. Estay Stange, Sens et musicalité, Paris, Garnier, 2014 ; P. Schaeffer, Traité des objets musicaux, Paris, Seuil, 1966. 10 Cf. Passions sans nom, op. cit., p. 46. 11 Ibid., p. 19 (our transl.). 12 “From Continuity to Rhythm”, art. cit., p. 93. 13 Cf. “From Continuity to Rhythm II. Adjustment and Entrainment”, Acta Semiotica, II, 4, 2022, p. 215. 14 Ibid., pp. 215, 224-5. 15 S. Smith, “What we meant by that was ‘let’s do this’. The interpretive metatext as pending account”, Actes Sémiotiques, 126, 2022. 16 “From Continuity to Rhythm II”, art. cit., p. 215. 17 Cf. E. Landowski, “Pourquoi le changement ?”, Acta Semiotica, III, 6, 2023, pp. 30-31. 18 Ibid., p. 31. 19 Sound Formations, op. cit., p. 170. 20 The term “goal” has little sense here, but I use it to respect Miranda’s definition of modulation (comparison of goal against performance to inform a modified repetition). 21 Cf. C. Preece et al., “Landing in affective atmospheres”, Marketing Theory, 22, 3, 2022. 22 Cf. S. Ahmed, The promise of happiness, Durham NC, Duke University Press, 2010. 23 Cf. F. Jullien, Nourrir sa vie. A l’écart du bonheur, Paris, Seuil, 2005. 24 C. Pépin and H. Rosa, “Comment entrer en résonance ?”, France Inter, 3 January 2024. See also H. Rosa, Resonance : A Sociology of Our Relationship to the World (2016), Cambridge, Polity, 2019. 25 C. Steadman and J. Coffin, “Consuming atmospheres. A journey through the past, present, and future of atmospheres in marketing”, in C. Steadman and J. Coffin (eds.), Consuming Atmospheres. Designing, Experiencing, and Researching Atmospheres in Consumption Spaces, Abingdon, Routledge, 2024, p. 8. 26 The spiral is perhaps the best spatial metaphor for this kind of processuality. Cf. E. Landowski, “Régimes d’espace”, Actes Sémiotiques, 113, 2010. 27 M.R. Jones, “Attending to musical events”, in M. R. Jones and S. Holleran (eds.), Cognitive bases of musical communication, Washington, American Psychological Association, 1992, p. 93. 28 As Jacques Fontanille wrote in his foreword to Les interactions risquées (op. cit.) : “The true value of the semiotics of interactions comes from the placement of the other, and of our interaction with the other, at the heart of the construction of meaning, right where tensive semiotics falls short, since it fails to go beyond (...) our sentient and cognitive relations with the world in general” (p. 4, our transl.). 29 Passions sans nom, op. cit., p. 176. 30 E. Manning, “Wondering the World Directly — or, How Movement Outruns the Subject”, Body & Society, 20, 2014, p. 171. 31 R. Chia, “Reflections : In Praise of Silent Transformation. Allowing Change Through ‘Letting Happen’”, Journal of Change Management, 14, 1, 2014 ; M. van Vuuren and B. Brummans, “Festina lente : Organizational Patience as Future-making Practice”, presented at European Group for Organizational Studies Colloquium, Cagliari, 6-8 July 2023. 32 Passions sans nom, op. cit., p. 157 (our transl.). 33 Traité des objets musicaux, op. cit., pp. 268, 342. 34 E. Landowski, “Le modèle interactionnel, version 2024”, Acta Semiotica, IV, 7, 2024, p. 122. 35 Traité des objets musicaux, op. cit., p. 478. 36 “Le modèle interactionnel...”, art. cit., p. 116. 37 Traité des objets musicaux, op. cit., pp. 332-3. 38 On this distinction applied to watching a film, see E. Landowski, “Unità del senso, pluralità di regimi”, in G. Marrone et al. (eds.), Narrazione ed esperienza, Rome, Meltemi, 2007. 39 S. Albert, When. The Art of Perfect Timing, San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 2013, pp. 20, 199-200. 40 Ibid., p. 205. 41 A.J. Greimas, Du sens II. Essais sémiotiques, Paris, Seuil, 1983, p. 34. 42 Cf. S. Smith, Switching Semiotic Styles during Health Emergencies : the Metachoices of Pandemic Communication, London, Routledge, forthcoming (2025). Résumé : Cet article donne à la socio-sémiotique une inflexion musicale. En partant du principe que le modèle des régimes de sens et d’interaction (tout comme le carré sémiotique) n’est pas une grille taxinomique mais un modèle de pratiques sociales situées qui lient et combinent plusieurs styles sémiotiques, j’envisage ses deux parcours typiques — l’un articulé autour de la manipulation, l’autre autour de l’ajustement — comme, respectivement, une sémiosis narrative et une sémiosis musicale. Ces deux sémiosis se démarquent à la fois par la manière dont elles relient les cycles d’action, par le fait que l’une tend vers un but alors que l’autre résonne avec une atmosphère, enfin par leur logique de changement ainsi que leur principe de timing respectifs. Une sémiosis musicale implique une configuration des événements en cours à la fois modulaire (modules se déroulant en parallèle, augmentant ou diminuant en sonorité) et modulante (perception d’un « problème » comme une chose en constante modulation, avec un rythme cyclique auquel la « solution » doit s’ajuster). Moyennant cette inflexion musicale, la sémiotique de l’expérience sensible est aussi une sémiotique de la performance répétée, durant laquelle se présentifient sentiments et attentes de changement pendant que nous avançons, à travers les répétitions modifiées, traversant les sillons parallèles. Resumo : Este artigo dá à sociossemiótica uma inflexão musical. Partindo do princípio que o modelo dos regimes de sentido e interação não é uma grade taxinômica mas uma síntaxe de práticas sociais em situação, que ligam e combinam estilos semióticos, considero os percursos articulados, um em termos de manipulação, o outro de ajustamento, como, respetivamente, uma semiosis narrativa e uma semiosis musical. Elas se distinguem a pelo modo como ligam os ciclos de ação, pelo fato que uma tende rumo um objetivo enquanto a outra ecoe uma atmosfera, assim que pela logica de mudança e seus princípios de timing. Uma semiosis musical implica uma configuração dos eventos tanto modular (modulos desarolando-se em paralelo, aumentando ou diminuindo em sonoridade) e modulante (percepção de um “problema” como uma coisa em constante modulação, com um ritmo cíclico ao qual a “solução” deve se ajustar). Com esta inflexão musical, a semiótica da experiência sensível é também uma semiótica da performance repetida, durante a qual se presentificam sentimentos e esperas de mudança ao passo que avançamos, mediante repetições modificadas, atravessando linhas paralelas. Abstract : This article gives a musical inflection to Landowski’s socio-semiotics. Starting from the premise that the regimes of interaction model (like the semiotic square itself) is not a classificatory grid but a dynamic model of situated social practices that traverse and combine semiotic styles, I imagine its two typical sensemaking pathways — one articulated around manipulation, the other around adjustment — as respectively narrative and musical semioses, which we can contrast on four axes : the way they span action cycles, their orientation towards goals or resonance with atmospheres, their logic of change and their timing principles. A musical semiosis means both a modular configuration of ongoingness (modules playing in parallel, fading up or down at moments of transition) and a modulating configuration of ongoingness (a perception of any “problem” as a modulating pattern with a cyclical rhythm, which our “solution” needs to adjust to). Given a musical inflection, a semiotics of sentient experience is also a semiotics of repeat performance, where feelings and expectations of change presentify as we move on, through modified repetitions, criss-crossing parallel tracks. Mots clefs : changement, modularité, modulation, répétition, résonance, rythme, sémiosis musicale, sémiosis narrative, timing. Auteurs cités : Stuart Albert, Rémy Bocquillon, Algirdas J. Greimas, François Jullien, Eric Landowski, Juan Felipe Miranda Medina, Chloe Preece, Hartmut Rosa. Plan : |

|

Pour citer ce document, choisir le format de citation : APA / ABNT / Vancouver |

|

Recebido em 29/07/2024. / Aceito em 10/10/2024. |