Derniers numéros

I | N° 1 | 2021

I | N° 2 | 2021

II | N° 3 | 2022

II | Nº 4 | 2022

III | Nº 5 | 2023

III | Nº 6 | 2023

IV | Nº 7 | 2024

IV | Nº 8 | 2024

V | Nº 9 | 2025

> Tous les numéros

Forum-dossier : Quelques paradoxes du « post- » consumérisme

|

Regimes of meaning and forms João Batista Ciaco Publié en ligne le 22 décembre 2021

|

|

|

Introduction : absolutely nothing ! In the short story that, in the Portuguese translation, lends the title of the book — Absolutamente nada e outras histórias (Absolutely nothing and other stories) —, Robert Walser introduces us to a woman who goes into town to buy herself and her husband something good for dinner1. But since her head is elsewhere, the woman carefully considers what she could buy that is both special and delicious for herself and her husband, but she cannot decide. She had no lack of good will or good intentions, but with her mind elsewhere she could only browse what to buy and, because of such a difficult choice, she did not buy anything2. When she gets home, her husband asks her what she has bought for dinner, and she says that she hasn’t bought anything at all. So, they ate absolutely nothing and were very satisfied, as it was extraordinarily delicious. And they contented themselves with absolutely nothing, although it is likely that many other things would please them more than absolutely nothing. |

1 R. Walser, Selected Stories, New York, Farrar, Straus, Giroux (eds), 1982. Tr. port. Absolutamente nada e outras histórias, São Paulo, Editora 34, 2014, pp. 71-73. 2 This reminds the behavior of the undecided thoughtful subject (“le pensif velléitaire”), identified as the one who “wonders to such an extent about his motivations and reasons to act, about what he would like to do, what he should or could do that, in the end, he never really does anything” (our translation). E. Landowski, Interações arriscadas, São Paulo, Estação das Letras e Cores, 2014, p. 43. |

|

Although this tale of the German-speaking Swiss was written at the beginning of the 20th century, therefore before the consolidation of marketing as a guiding mechanism for capitalist companies and even before the full structuring of the mass market, it already presents consumption as a practice that follows modern life almost structurally. It is true that, in Walser’s narratives, social customs, human dreams and relationships are relegated to a smaller category, to an almost unimportance, but the purchasing process is presented by him as a complex exercise, which demands a competence whose modal structure of wanting and having to get something good for dinner is conditioned to a type of knowledge that requires full dedication and exclusive attention — and that does not allow the train of thought to vanish in a direction other than absolute devotion to the act of consuming. |

|

|

As Greimas pointed out, if the act is a “make be”, competence is exactly “the thing that makes be”, that one thing that allows the act to be carried out, that is, all the preliminaries and assumptions that make the action possible3. The modal competences of the making-believe, as well as the semantics that legitimise them, make it possible to perform the act, even without realising the purchase, with the subjects believing that they are absolutely satisfied with absolutely nothing. We can thus infer that the concept of consuming organises, in Walser’s very short tale, at least three distinct narrative programs : that of the desire and planning by the woman as she wants to buy something good for her husband’s dinner, the other, of the very act of buying in the face of difficult choices among so many possibilities and, finally, the consummation of what is, or is not, acquired, embodied by the dinner and by the complete satiation with absolutely nothing. |

3 A.J. Greimas e J. Courtés, Dicionário de Semiótica, São Paulo, Cultrix (without datation), p. 62. |

|

Consumption, as we well know, is an act of everyday life that can even be considered ordinary. On the other hand, it also refers to complex phenomena that institute great challenges, both for professionals trying to understand and analyse them, such as sociologists, anthropologists, economists and semioticians, as well as for marketing professionals, who seek to manage it in order to operate their mercantile goals on it, as well as the consumers themselves, who use consumption for many other purposes than just that of satisfying their needs. |

|

|

Comprising several narrative programs and providing so many incitements, consumption is an ambiguous concept, being sometimes understood as manipulation and use, at other times as acquisition and purchase, still as experience and, occasionally, even as exhaustion, depletion, erasure, or disappearance4. Positive and negative significations are interwoven in the daily practices of relating to our needs, our desires, our social behaviors and even with our processes of identification and presence in the world. The fact is that consumption presents itself as one of the most striking and inseparable characteristics of contemporary society, as post-modern sociologists have shown so well. |

4 Cf. entry “consumir” (to consume) in Grande Dicionário Houaiss da Língua Portuguesa, online version, https://houaiss.uol.com.br/corporativo/apps/uol_www/v5-4/html/index.php#6, 02/09/2021. |

|

Concomitantly with the overvaluation of consumption in the post-modern daily life, we can also paradoxically identify that contemporary society experiences an opposite movement towards a certain “detachment” from things, which leads, on the one hand, to the disposability of consumer objects and, on the other hand, to the uninterrupted renewal of products and the very act of consuming. In fact, in the post-modern consumption process, consumers seem to use products much more as means of communication, that is, they are much more focused on how the product and its consumption are perceived by others than effectively on its functionality5. |

5 Cf. Y. Acar, “Post Consumption”, in H. Babacan and B.C. Tanritanir (eds.), Current Researches in Humanities and Social Sciences, Montenegro, Ivpe Cetinje, 2020, pp. 310-325. |

|

If these dynamics promote a certain desemanticisation of consumption objects in themselves, it can be assumed that, for consumers, what is valued is a given search for the new, to look like other, while what is actually craved is almost only a virtuality of consummation, without its necessary fulfillment. The desire for the new, for the novelty, is often stronger than that carried out in its material or immaterial consumption or, in another way, the need and desire to acquire or own something seems to be much more fruitful for the post-modern consumer than the object to be effectively consumed6. |

6 Cf. J.B. Ciaco, A inovação em discursos publicitários : comunicação, semiótica e marketing. São Paulo, Estação das Letras e Cores, 2013. |

|

1. The consumer, marketing, and consumption practices The essence of the marketing role is the promotion of consumption. Philip Kotler presents it as a “social process through which people and groups of people get what they need and want from creating, offering and freely exchanging valuable products and services with other people”7.The understanding of what is necessary and desired, even if on an individual basis, is only achieved through marketing, obviously, through social, cultural and even moral mechanisms that, for this purpose, organise criteria and rhetoric to explain, justify and legitimise what we consume and how we do it8. The mechanisms that allow justifying individual and collective choices of what and how to consume, being able to tell the basic need from the superfluous, the necessary from the futile, the fair from the immoral, the sustainable from the unsafe, erect social behavior practices in the face of consumption that allow us to better apprehend the forms of identification and presence of individuals as subjects of consumption. |

7 P. Kotler, Administração de marketing : a edição do novo milênio, São Paulo, Prentice Hall, 2000, p. 30 (our translation). 8 Some of these criteria were even organised into psychosocial theories, such as Abraham Maslow’s Theory of the Hierarchy of Needs, widely used in administration and marketing, in which the author ranks five categories of human needs in a pyramid, ranging from the most basic to those of self-fulfillment, in which an individual only feels the desire to satisfy the need for a higher level if the previous one has already been satisfied. Cf. A teoria de Maslow, P. Kotler, op.cit, p. 194-195. |

|

The world of consumption and marketing itself have been experiencing profound changes. Marketing reorganises its strategies and practices, turning further to the construction of brand values and purposes, to its insertion in the dynamics imposed by the convergence of participatory media and to the expansion of the look beyond the relationships based on the act of consuming. Some call this stage marketing 4.0, others post-marketing, or even post-consumption marketing. However, the most plural characteristic of this new marketing process is given by such an intense and definitive assimilation of digital technology in all processes and strategies that it goes unnoticed, unrevealed, most of the time. This digital ubiquity in marketing practices, which is so excessive it becomes absorbed, so ubiquitous it becomes diluted, brings about this new moment that can be named post-digital marketing. |

|

|

On the other hand, the post-modern consumers can be seen, in Giampaolo Fabris’s presentation, as more autonomous, critical, competent, much more informed, demanding, selective subjects, attentive to their needs and rigorous about their choices9. Just saying that it is a new consumer built in the rites of post-modernity is an incautious and almost banal construction, since consumption is a social and historical production, as a provisioning system, which enables not only the acquisition of objects, but, above all, to institute a system of practices that form the very structure of social roles. But what then would this contemporary subject of consumption be ? One may speak about the hyper-consumer, the turbo-consumer, the non-consumer, the post-modern consumer, the post-consumer, among many other terminologies. |

9 See G. Fabris, Il nuovo consumatore : verso il postmoderno, Milan, FrancoAngeli, 2003. |

|

Historian Eric Hobsbawn warns us that sometimes, when we face what the past has not prepared us to face, we try to look for words to name the unknown, even when we cannot define it or, possibly, understand it. This is the case of the preposition “after”, used in the Latinate form post : “the world... became post-industrial, post-imperial, post-modern, post-structuralist, post-Gutenberg, or whatever. Like funerals, these prefixes took official recognition of death without implying any consensus, or indeed certainty, about the nature of life after death”10. It is therefore necessary, even imperative, to try to seek a better understanding of this structuring subject of contemporary consumption, in order to allow us to scrutinise its status in life practices motivated by post-digital marketing strategies. |

10 E. Hobsbawn, The Age of Extremes : 1914-1991, London, Hachette UK, 2020, p. 288. |

|

A first step that seems to help us in this quest, in this challenge, is to understand that the proximity — intimacy, even — that occurs between the world of consumption and that of post-modernity in which it is inserted occurs through the sharing of the values of individualism, the reappraisal of the body, the relentless pursuit of happiness and pleasure, as well as all the immaterial elements that consumption makes it possible to achieve11. It is relevant to think of consumption objects (goods, services and the very act of consuming) in these terms, as objects of value along the way Greimas conceives of them in his narrative grammar — as places of investment of values with which the subjects put themselves in conjunction or disjunction12. The “junction”, in this way, presents itself as a relationship that determines the state and situation of the subject in front of the object. In other terms, (con)junction allows the subjects to access the values invested in the objects. |

11 Cf. A. Semprini, A Marca Pós-Moderna. Poder e Fragilidade da Marca na Sociedade Contemporânea, São Paulo, Estação das Letras e Cores, 2006, pp. 60-70. 12 Cf. A.J. Greimas and J. Courtés, op.cit., pp. 312-313, entry objeto (object, our translation). |

|

To adopt practices and rites of consumption allows the consumer full access to the values that “being together” may bring, whether in the order of the subject’s states in relation to the world and themselves (since, after all, “I am what I consume”, as marketing spreads out to all corners so well), or in the order of doing, that is of the transformations on the world, which the mediation of objects enables to perform. Being disjoined from the value-objects of consumption results in narrative paths to overcome the shortage of the desired values. Therefore, if consumption can be understood as a search and occupation of the subjects individually, consumerism expands in the direction of being understood as a social attribute, a “propulsive and operative force of society, a force that coordinates the systemic reproduction, social integration and stratification (...) at the same time playing an important role in the processes of individual and group self-identification, as well as in the selection and execution of individual life policies”13. |

13 Z. Bauman, Vida para Consumo : a transformação das pessoas em mercadoria, Rio de Janeiro, Zahar, 2008, p. 41 (our translation). |

|

On the other hand, if the junction helps us to understand the circulation of values in the hyper-consumption society, more recent movements point to another direction in which sustainability, concerns about the environment, about the origin of products, about the forms of production, about the use of natural resources and disposability create new dynamics between subjects and between them and the world of consumption. Other routines of reuse and recycling occupy more and more space and delimitate, if not other forms of consumption, at least practices of consuming differently. Furthermore, the very act of not consuming seems to also allow a relevant meaning for other social actors, who start adopting non-consumerist practices, if not directly anti-consumerism, which determine their ways of interacting with and for others. Thus, concomitantly with the apprehension of consumer objects as objects-value of post-modern society, another dynamic appears which stresses the importance of acting in the face of consequences and attitudes that are deemed “too consumerist”, causing a shift in the apprehension of consumption from its values to its effects and thereby in the forms of interaction among the subjects of consumption. The degree of importance, of necessity, given to “acting based on consumption” and which requires an absolute urgency — as ecologists, environmental activists and anti-consumerists want — or a relative urgency, as the most incautious consumers may wish, shows us that there is another dynamic that is founded on the apprehension of consumption based on the face-to-face interaction of the subjects in copresence. Consumption then becomes meaningful not anymore as a material reality that carries the values of the post-modern world, but because of its sensitive qualities that motivate interactions between subjects. This new orientation is commanded by some underlying principles which are semiotically distinct from those which rule the logic of “junction”. These other principles are those which operate in what the sociosemioticians term the logic of union14. While in the logic of junction the understanding of the world depends on the cognitive apprehension of the objects of consumption as a network of signifiers to be deciphered, in the logic of union the subjects let themselves to be “impregnated by the sensitive qualities inherent to the things themselves”15. |

14 About the concepts of union and junction, cf. E. Landowski, “Jonction versus Union”, Passions sans nom, Paris, P.U.F., 2004, pp. 57-69. 15 E. Landowski, “Sociossemiótica : uma teoria geral do sentido”, Galáxia, 27, 2014, p. 13 (our translation). |

|

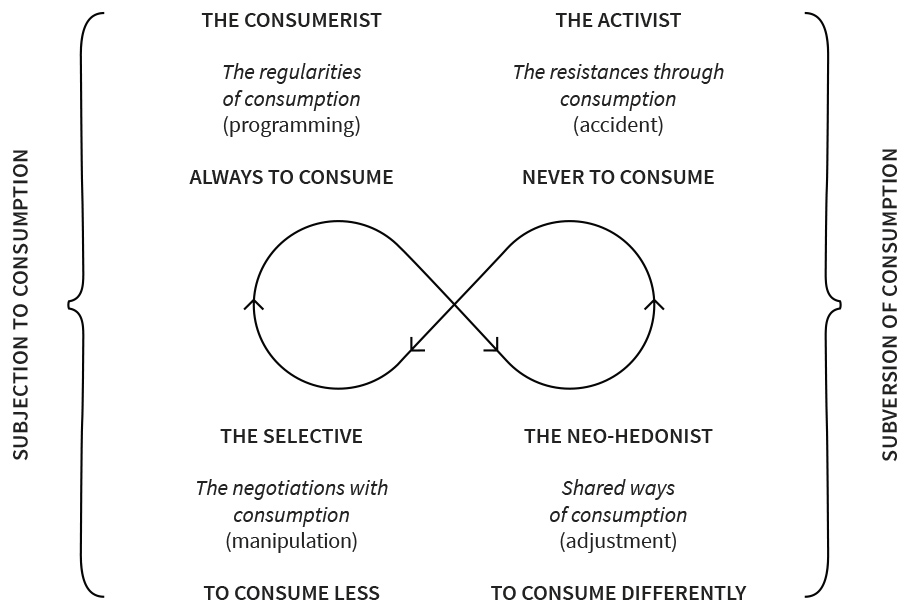

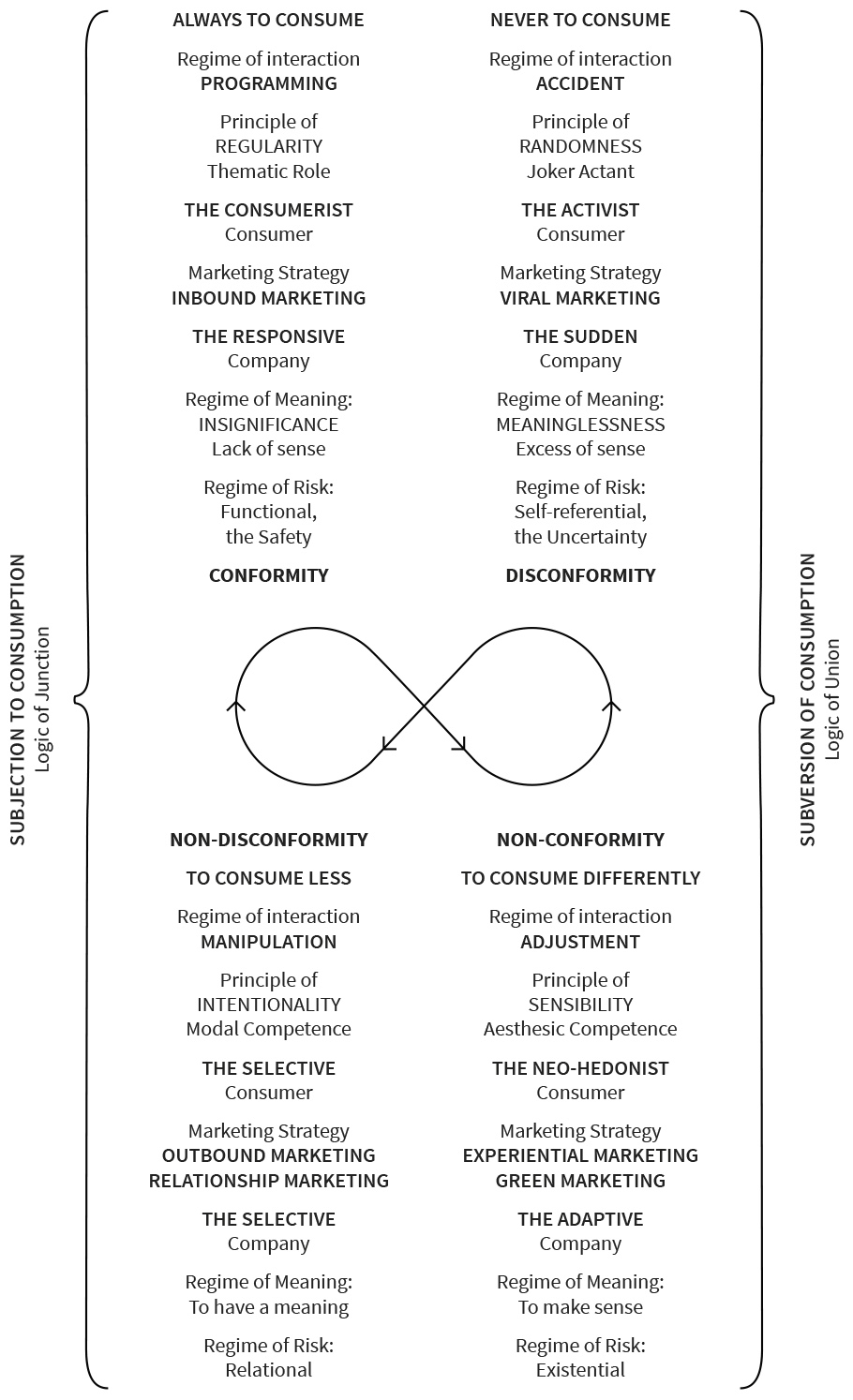

2. Lifestyles, ways of consumption It would not be an exaggeration to infer that contemporary consumption, hyperbolic and omnipresent, becomes a kind of morality of the contemporary world, as it organises a certain resignification of human relations from the momentary satisfaction of needs created individually and socially, in a continuum marked by the insatiability in which a satisfied need almost automatically generates another, in a cycle in which the act of consuming becomes the desire for consumption itself. We shall call this practice consumerism. In an attempt to better identify the status of this “post”-consumer, it is necessary in the first place to specify the founding, basic and organising relationship of the interactions and practices of this “apostle of consumption”. This relationship seems to be built from the eagerness of the subjects to subjugate themselves (or not) to the propositions of consumption, that is, in their willingness whether to embrace the dynamics of consumerism or to reject its provocations, viewed as hyper-consumption. Therefore, the minimal semantic operation to understand the condition of this consumer in the post-digital world seems to be drawn from the opposition of conformity versus disconformity to the rites and practices of consumption. To conform to the dynamics of consumption is to surrender to the programs that consumerism organises, letting oneself be seduced by the promises of a greater well-being, of a programmed personal fulfillment, of being the master of immediate time and emotional comfort that the world of consumption promises to fulfill. On the other hand, failing to conform to the practices of consumerism is, initially, not understanding them as bearers of crystallized values, holders of previous meanings of individual and collective achievement, but, on the contrary, letting to be penetrated by the sensitive qualities they can provide, constructed and reconstructed in the very act of interaction. |

|

|

2.1. The consumerist and the regularity of consumption From the opposition conformity vs disconformity, we can identify a first regime regarding the situation of full submission of the subjects to the rites of hyper-consumption. Unlike consumption, which is basically a characteristic of human beings as individuals, consumerism, as we have seen, even if operated individually, is an external attribute, socially conditioned. Consequently, the deeply individual capacity of wanting is alienated from individuals and reified in an external force that moves the social and the collective. This does not mean, however, that there is a disposition to the social aspect based on consumerist practices. On the contrary, this extreme consumption is aimed at a search for “pleasure for oneself”, that is, consumption aimed at intimate enjoyment, towards the qualities of the object, towards the quest for the always new, towards autonomy and individual happiness as the purpose of life. Pleasure is directly associated with the acquisition and consumption of goods and these voracious consumers, programmed to respond to all calls, we name them consumerists. The most visible values in consumerist life practices, in fact, their supreme values, are those of an inexhaustible pleasure, an instantaneous happiness, indefinitely renewed through consumption. The consumerist, in this way, is programmed to seek pleasure through consumption. The operating condition of this regime is the constancy and regularity of actions and reactions, behaviors and their determinants : the actions and practices imposed by companies, brands and the consumer market correspond to programmed responses of the consumerist subject through the rites and habits of consumption. In a word, the principle of this regime of interaction, the “programming”, is regularity, which assigns to the interactants the thematic roles that semantically delimit their spheres of action. The principle of regularity establishes a very deterministic way of understanding the world. In relation to the voracious search for the immediate pleasure that determines the consumerist subject’s actions, emerges a social organisation of consumption that can only prosper if it manages to perpetuate the non-satisfaction of the desires generated by itself. As an economic dynamic — and even as an economy of the senses — consumer products are devalued and depreciated soon after they have been promoted to the universe of desire. Without this repeated frustration, without the iteration of interrupted enjoyment, the demand for consumption would soon exhaust in itself. Therefore, the consumerist dynamic needs to be based on excess and waste. In this way, we can say that the regime of meaning associated with this programmatic regime of interaction is that of insignificance, since the search for pleasure through consumption, instead of being ever achieved in the act of consumption, is an eternally postponed, virtualized pleasure. Thus, ad infinitum consumption programs are established, aiming to satisfy desires that the very dynamics of the dispositive makes unachievable. |

|

|

2.2. The activist and the resisted consumption In an opposite direction, we find consumers who are frontally opposed to hyper-consumption, rejecting the imposition of obtaining satisfaction, pleasure, and happiness only through the dynamics of consumption. More than that, they propose some criticism of the consumerist spirit, organising forms of interaction that encourage the breaking of submission to the established order. They operate, therefore, in disconformity with the logic of consumption. We call this “post”-consumption subject an activist. The activists, in fact, cannot readily apprehend any value that consumption may condense. They do not even lend a negative value to it, condition that distances us from a logic of junction. By not being able to locate readily apprehensible values in consumption (operating by the logic of union, in this way), they allow themselves to be impregnated by its sensitive qualities, to question it, challenge it, confront it, deny it, and eventually forget about it. The activists thus challenge the (narrative and life) programs that consumption imposes on them. Thus, the activists can demand changes in society and in the forms of interaction between brands, companies, and the subjects of consumption. These consumers aim, in this way, to express their contentment, disappointments and unease with life issues (whether of an economic or social order) through political attitudes that have consumption practices as a vector, as a catalyst. We can identify some of this activist consumer’s ways of operating. These behaviors imply motivations that range from resistance and boycott to certain forms of consumption, based on environmental, social, economic, or cultural issues and carried out by the desire of a healthier, more responsible and more collective life, to what we can call anarchist activism against the very economic system that sustains hyper-consumption. Activists act to pressure the system for the purpose of altering consumption practices deemed inappropriate or unreasonable and emphasise the need to raise collective consciousness and, through it, change the culture and ideology of consumption. Evidently, a life without consumption and a lifestyle without consuming, although occasionally desired in very specific situations and groups, is poorly practical and achievable, which can make activist programs sometimes chaotic or ultimately senseless. Such a demand of changes in society is obviously not a recent movement. However, what makes this moment of activism different is its possible practices based on the dynamics of the post-digital world. Testimonies of people against companies and brands for different reasons are everywhere on social media and digital platforms, ranging from individual dissatisfaction to accusations about production processes (the use of forced or child labor, use of raw material of dubious origin, lack of attention to the disposal of products after consumption, among many others), and even on the inappropriate uses of advertising and communication (due to the objectification of the female body and the lack of representation of social diversities). A particular type of this activism is what marketing designates as market activism, when a critique of consumerism emerges, attacking a company or brand for its negative social, environmental, or human impact. One of its visible forms is culture jamming, a practice that re-operates the very communication process of these companies in an ironic and even sarcastic way, trying to discredit the brand and, by extension, the market capitalism. This post-consumer digital culture is known as NetActivism. Through it, the figures of the lover (passionate consumers, advocates, and disseminators) and the hater (critics and saboteurs) gain evidence, people who take a stance politically and in networks (even as activists) in the face of new dynamics and challenges in the world of consumption16. |

16 Cf. I. Domingues and A.P. Miranda, Consumo de Ativismo, São Paulo, Estação das Letras e Cores, 2018, pp. 57-71. |

|

The risks involved in this type of regime consist, in general, in the possibility, or probability, of not achieving adhesion or visibility, being only restricted to those who promote them. In case they achieve effective reach and social impact, it may be not enough to lead companies (and society) to reorganise their consumption and life practices. For activism, as for all activities in life, there is a gradation of risks both in the success of an implemented program and in its failure. If it fails, it is because it is nothing more than “good ideas, but of little applicability”, as pragmatists would put it. Or, it might be just “unreasonable ideas, which do not deserve attention”, as the skeptics would say. Or even it might be judged “too dangerous” and needing to be stopped. In any case, the activists are in danger of presenting themselves as ill-considered, even foolish. What mobilises the activists’ drive then emerges as the negative of the category whose positive term is programming, namely the regime of the accident, which is based on the principle of randomness. For the activist, there are also risks in achieving success. Not those of the full implementation of the proposed programs, but those that show themselves after their successful completion, which can make the activists find themselves as “fighters without a cause” who, after doing so much, becomes inert, meaningless. And there is also the extreme risk that a resistance action provides an exact opposite result from the one intended. Some culture jamming actions, for example, when protesting against a brand, bring that brand an increased notoriety within certain audiences and its sales, contrary to expectations, increase due to better visibility. |

|

|

The activist, in this way, cannot have the role of organisers of the possible programs based on their practices of resistance to consumption, since they depend on so many unplanned factors, as well as a good deal of chance. Therefore, they only have one role, which is that of the joker actant : “as the joker or the trump card in certain card games, their role is to have no role at all, or rather, to be able to fulfill them all”17. And this demodalized actor seems to play its role in a catalytic way by motivating actions and reactions around them (just like chemical catalysts), accelerating and enhancing the transformation processes without, however, consuming themselves. |

17 Interações arriscadas, op.cit., p. 79 (our translation). |

|

2.3. The selective and the negotiated consumption We can also identify in the interactions of the post-digital world those who are not subject to consumerism, although they do not distance themselves from the consumption dynamics. These subjects do not defend the rupture with excessive consumption, but they also do not assimilate it, since the consumerist lifestyle generates, in their view, extreme individual stress, irresolute and endless desires, frustration by the incessant search for individual pleasure, unhappiness and thus the lack of well-being. These subjects seek to organise themselves for a lower, selected, simplified consumption that enables a better quality of life, establishing interactions of the order of non-disconformity with consumption rites. These are selective consumers. They do not fail to perceive value in consumption, in consuming, as their life practices are organised by the drive of remaining conjoint to it. But they do not accept all the programs and rules that the contemporary world of consumption establishes, preferring to negotiate the values that most satisfy them, that best identify them and that, in a convenient way, make-them subjects of their life practices. Selective consumers seek paths that oppose materialistic and high-consumption lifestyles, aiming for an “easier, more practical”, more meaningful life. In other words, they consume less, and better, in their belief. They choose goods and forms of consumption for personal reasons (products with less sodium, lactose-free or gluten-free, adherence to veganism, a more expensive but longer-lasting brand, for example) or collective ones (cosmetics companies that do not test on animals, or do not use plastic in their packages). If the selective consumers seek to give meaning to their life practices by negotiating the values that motivate them the most — because they convey more meaning — they also are open to changes in the rites and practices of consumption, as is the case with activist consumers, although in a very different manner. While activists try to impose change through denial, resistance, non-consumption, selective ones prefer to negotiate reduction and screening strategies of what to consume. In this type of interaction, interactants operate in the regime of manipulation, founded on the intentionality of the subjects. The competence of these subjects is basically based on cognitive elements. To manipulate the other is to make them want-to-do. But for this to happen, it is first necessary to make them aware of the advantages entailed by their expected acceptance of such or such a proposal. Movements such as One day without car, Six items or less or Buy nothing week are examples of programs that car companies, consumer goods and even retailers are willing to implement and negotiate to keep their consumers close and, especially, ensuring that these selective consumers, even if consuming less on specific occasions, do not cease to be seduced by the values that these companies insist on reifying. Another practice linked to selective consumption programs concerns a certain stance against the ideological manipulation of big brands. The anti-loyalty movement (or No Logo movement, reverberated by Naomi Klein18), that proclaims no loyalty to brands, is a growing strategy in the consumer market and it demands immediate reactions from companies and brands. |

18 N. Klein, Sem Logo : a tirania das marcas em um planeta vendido, Rio de Janeiro, Record, 2004. |

|

2.4. The neo-hedonist and the shared consumption In connection with a fourth regime of interaction, we can identify, in the post-digital world, those who are against consumerist practices and “exaggerated” consumption but do not go as far as directing their anger towards the consumption establishment, as anarchist activists do. They prefer to approach how to heal the wounds, the pains and even the voids that individuals are trying to fulfill with hyper-consumption. These rather critical consumers do not believe that resisting consumption is the best alternative, nor do they consider that manipulating companies and the market to reduce consumption is the most fruitful path. |

|

|

One of the characteristics of post-modern times, as already postulated, is the pursuit of pleasure and the achievement of “experiences” through consumption19. Pleasure, the principle of hedonism, becomes the condition for the subjects of post-modernity to achieve happiness and this is supposed to be achieved through the acquisition and consumption of goods and services. Hedonistic consumption, by definition, is closely related to consumerist practices. However, this eternal search for ephemeral pleasure and happiness based on consumption seems contradictory. On the one hand, it is necessary to consume more to open up to the world in the constant search for new experiences and in an attempt to satisfy an insatiable quest for pleasure, while happiness vanishes even before it is accomplished. But at the same time, it is necessary to consume less to deal with the social, environmental and economic problems that the consumption dynamics impose on society, in order to contribute to an individual and collective quality of life, and to a more responsible existence. This dichotomy, which for Lipovetsky establishes one of the great paradoxes of the society of hyper-consumption — what he calls paradoxical happiness20 — brings about a new subject of consumption, which we will call neo-hedonist. |

19 For a critical perspective about this point, see, in the present issue, A. Perusset, “L’expérience au cœur du marketing postmoderne”, Acta Semiotica, I, 2, 2021. 20 G. Lipovetsky, A felicidade paradoxal : ensaios sobre a sociedade do hiperconsumo, São Paulo, Companhia das Letras, 2007. |

|

Acting towards a non-conformity with hyperbolic consumption practices, such “post”-consumption subjects believe that there is no way to neutralise the dictates, rules and programs that are imposed on them simply by “pulling off the bandage to leave the wound exposed”, or by proclaiming : “Never consume again !”. It is a journey that is intertwined in a long tangle of emotional obstacles that requires a solidary approach that moves away from the persuasion between intelligences and can only walk towards a contagion between sensibilities. Unlike the selective consumer who seeks to consume less, electively, and to convince other people to reorganise their consumption practices (a strategy that is often answered by companies and brands in a reciprocal manipulation movement well-known in marketing programs), the neo-hedonists are not opposed to consumption by itself, but rather search alternatives to the existing forms and practices of the consumption system. They seek to consume in a different manner. These new ways of consuming lead to individual practices — such as product recycling, reuse and waste reduction — that transfuse into collective subjects, in a movement that involve the social forms of being together because they require a new personal and collective organisation. More than that, these practices entail new programs : separating garbage and trash requires a new spatial arrangement in homes and offices for selective collection ; not using plastic bags transforms the routine of going to the supermarket. Other practices related to the neo-hedonist propositions create more interactive and shared ways of consuming, such as car sharing, shared houses and offices, renting toys for children instead of purchasing them, bicycles and scooters hired by the hour to improve urban mobility, among many others. To eat what you plant, to use what you recycle, bringing production and consumption closer together and reducing waste pertains also to this way of consuming. What makes selective practices different from the neo-hedonists ones is that in the latter there is no political motivation as regards consumption. It operates at the level of daily life according to forms of practical “adjustments”. And while the activist’s central motivation is to dismantle the consumer system by resistance to consumerist practices and even fight against corporations, the neo-hedonist believes that change must come from an intimate, individual and personal level, because it supposes the reciprocity of intersubjective adjustments. And what allows them to adjust to the other is their aesthesic competence, which gives them the ability to feel in harmony with the other, reciprocally. The universe of neo-hedonist consumption, precisely because of the aesthesic competence of the subjects, allowed for the emergence of important economic and social movements of wide scope, such as the circular economy, the conscious consumption and the creative economy. These distinctions between consumption modes may be schematised by the following diagram.

|

|

|

3. Marketing strategies, meaning strategies At a general level, strategy presents itself as a methodology of human action to achieve a specific objective. In the marketing domains, strategies aim at organising the available resources so that the market purposes are achieved and the results maximised. It is, in other words, a process of decision and action (an intention) through which the company identifies its target (the subjects with whom it will operate), defining its resource allocation (its competences) and its priorities and achievement processes (the action itself). In this operational view of the company’s strategic action, we turn to actions that bring brands closer to their consumers with the ultimate purpose of sustaining consumption, both present (sale) and future (brand loyalty). But, at the same time, another field of possibilities is established in the competitive dynamics of the market for companies and brands to introduce themselves to each other and, in this field of interaction, convey their wills and actions to competitors, on the one hand, or conceal them, on the other hand. Furthermore, they may simulate certain intentions to make the others act and react. Thus, it is possible to show how, within each of the interaction regimes we have already referred to, marketing strategies operate to better achieve their market objectives. But it is also essential to understand the competitive mechanisms that are intertwined between companies in each of these regimes, foreseeing the meanings that emerge from the market and competitors’ actions. |

|

|

3.1. Automation and digital algorithms Marketing operates to understand consumerist “post”-consumers beyond their individual desires, seeking regularities based on their behaviors and on all levels of their interaction with the brand. Once the consumerists devote themselves to the principles of consumption, willing to comply with all the programs offered to them, a marketing dynamic may be instituted to program all these interactions between them and the brands. The new information technologies incorporated by marketing start allowing deep processes of segmentation of these consumers by sociodemographic and psychographic data, geolocation, digital and social behavior, income, among many others, which enable to stop regarding consumers as unpredictable beings and instead, to group, mold, departmentalise, and watch them to exhaustion. This marketing automation strategy based on the regime of programming is known as Inbound Marketing (or Attraction Marketing). Founded on the principles of content creation, optimisation of online search systems (SEO, Search Engine Optimisation) and social media strategies, Inbound Marketing uses algorithms that monitor in detail the behaviour of consumers in the digital and social world, so that generalisations can be elaborated and, based on them, programs to reach exactly each of these “bare consumers”. The “marketing funnel” is a model that represents the audience’s journey from the moment the consumer has the first contact with the company or brand (on the internet, on social networks, at the point of sale, etc.) until the moment of purchase, repurchase and the building of loyalty ; the construction of personas, modeling of fictional characters that virtually express the exact behavior of real consumers and the programmatic media, a strategy aimed at programming communication so that it reaches the customer with the exact content, in the most appropriate media and at the precise moment for the consumers to be attracted to the brand’s digital and social properties. Due to the rigid control of unlimited programming, the risks of implementing inbound marketing actions are many : consumers who do not allow themselves to be operated by the excessive or insufficient force of a specific programming ; greed in corporate action that frightens the consumer ; algorithms that are too generic and incapable of convincing ; media platforms programmed so oppressively that they embarrass the brand and the company. In any case, in this exhaustively controlled environment, governed by competitive dynamics of the numerical order, the quantitative and the measurable, in which the objective is resolutely to reduce the risks of the operation and the business, only companies that are able to program their interactions in the market, detailing their competitive actions and their responses for a controlled action can effectively operate. We name responsive those companies that manage to operate in the regime of programming and under the aegis of inbound marketing, as they are strategically always ready to react with constancy and little flexibility in an environment that they fully know and control. |

|

|

3.2. Between probability and randomness In the opposite direction — that of the regime of accident — and from the perspective of marketing strategies, the initiatives, actions and reactions of the activist consumer appear as a mathematical probability given a priori. In other words, companies and brands usually try to foresee the possibilities of boycott, protest or resistance actions and build their crisis management programs to face such situations. Extensive documentation of the riskiest topics is built, manuals with answers that were written and rewritten to exhaustion, carefully revised communications for the different audiences and thorough detailed programs are prepared. When detaching the activism actions from the sphere of randomness to that of mathematical probability, one migrates to the programming regime and, effectively, this is what the marketing departments are responsible for doing : good action and reaction programs and good crisis management practices. In spite of that, when any activist demonstration takes place, or when randomness produces an accident that disturbs the established order, the company does not cease to be surprised in a sudden, unpredictable way. In such case, and however programmed it may be, the “meaning” can only be that of a sheer non-sense which imposes itself so unilaterally that the only gesture that is possible to answer it is of the order of exclamation. Certainly, management and crisis programs can handle, if the mathematical probabilities are confirmed, the “expected accidents” for which the responses are programmed to mobilize the moods and desires of the most incisive activists. But these, far from being effective marketing strategies, are momentary and occasional actions that seek to reduce the company's risks in loosely controlled environments. However, the most common marketing strategy implemented by brands, also operating in the regime of accident, is called “viral” marketing. If activism happens so intensely in the digital environment through the actions of NetActivism, as already discussed, in the presence of haters and lovers who propagate negative and positive content from brands and companies, viral marketing is a marketing aspect aimed at ensuring that certain content is shared, commented on, and viewed from the dynamics created by the actions of the consumers themselves. It is, thus, a strategy that encourages the engagement of the company’s audiences so that they can pass it on, go viral, spread the messages and communications that were created. Heir to what in the offline world was called “word of mouth” and adjusted to social and digital platforms, the main characteristic of viral marketing is to make people, by individual and independent decision, act as propagators of the brand messages. Certainly, a high-risk operation, since the adherence to sharing has no guarantee of occurring, as well as there is no formula, or schedule, to ensure the success of the initiative. Evidently, some resources are used by marketing to increase the probability of success, such as the eventual hiring of people with a strong presence on the networks — digital influencers, as they are known —, which help to encourage the circulation, sharing and engagement of messages. There is a certain stratification of viral marketing activities. There are the spontaneous messages, which sprout up from routine interactions between brands and their consumers, which can draw attention due to some peculiarity or surprise, because they are fun (as is the case with memes) or because of the high relevance of the information. There are also messages programmed to spread positive elements of the company, which operate as an online communication campaign circulated by “lovers”. Another viral marketing initiative concerns campaigns created to confront boycott initiatives or “haters” taking sides, whose purpose is to neutralize attacks by mobilizing lovers and brand defenders, operating on the same battlefront chosen by activists. There is yet another important viral marketing initiative called “content overlay”. When the company is surprised by any accident that generates great social mobilisation, whether by chance or motivated by an activist approach, and also when the programmed responses are not enough to stop the negative impacts, the brand creates a “new fact”, a high-impact subject that manages to override the negative one and therefore try to shift the public’s eye to another direction that is less harmful to the company’s reputation. |

|

|

Since there is no way to program the fruition and acceptance of the proposed communicative game, as there is no guarantee against “pure luck”, the risk of the viral marketing strategy falls on the brand itself, which is why this type of risk is qualified, according to Landowski, as a “self-referential” risk21. On the other hand, companies that operate under the regime of accident, which need to give up a more rigid marketing planning, only counting on the chance of achieving surprising results in the face of the unexpected and whose strategies are punctual and short-lived, can be called “sudden” companies. To try to control high risks, or at least to try to calculate their chances of success, these companies need to be ready to quickly change the strategic direction of their decisions and communications, surprising the market with new products or services when activist forces cannot be minimized or controlled. |

21 Interações arriscadas, op.cit., p. 99 |

|

In the regime of manipulation, in which selective subjects negotiate ways to consume less and in more significant ways, not avidly surrendering to the pleasures of hyper-consumption, on the one hand, but not willing to abandon them, on the other hand, marketing needs a strategy based on persuasion, seduction, temptation and eventually intimidation to strategically manipulate these agents of consumption. This is a well-known marketing arrangement, and which is now called Outbound Marketing or, more simply, Traditional Marketing. Unlike inbound marketing, which stratifies and personalizes communicative content, convincing the customer to reach out to the company and the brand (in person or online), outbound marketing reaches the selective consumer through a more general, totalizing and uniting communication, via offline mass media (television, radio, newspapers, sponsorships, events, etc.) and even online (websites’ homepages, for example). With the evolution of digital and social media and, especially, with the sophistication of search tools such as Google, brands that manage to work assertively with their optimization tools (SEO) end up with good visibility in these search engines and are found by their customers. Therefore, the need for companies to seek out their customers, to reach out to them through traditional advertising, is eventually minimised, in addition to the fact that the operation cost of outbound marketing is much higher and provides less effectiveness in measuring the results. Outbound marketing, in this way, eventually loses its relevance within the general post-digital marketing strategies, although it is still widely used by companies, mainly by big brands. An important first step for outbound marketing strategies is the recognition of selective consumers as subjects endowed with will and intention, and then try to convince them of the “value of the value” of their products. If the manipulation succeeds, by any of its mechanisms, and if consumption occurs (acquisition or use), then a second necessary step for this type of strategy is the search for loyalty of this selective consumer. If the purpose of strategic manipulation is the fulfillment of consumption, seen as a punctual act and negotiated at each interaction, loyalty is a manipulation of lasting scope, by which it is no longer necessary to act point by point, consumption by consumption, desire to desire. A lasting intentionality is established, through which new and successive acts of consuming are developed without the need for a new strategic negotiation. But for this long-term negotiated will to be achieved, it must be frequently remembered, valued, nurtured, as they say in marketing jargon, which is why companies build their relationship rules whose purpose is to organise future interactions that will enable the maintenance of the loyalty programs. This strategy that accompanies outbound marketing is called Relationship Marketing and, based on a set of pre-designed operations, it often ends up shifting to another regime, that of programming, as it starts to be implemented. The competitive market scenario, in which several brands try to manipulate these selective consumers, is usually quite competitive and with large offers of products and services. Normally, for brands that operate in the regime of manipulation, not all competitive attacks justify a reaction, leading them to recognise the strengths and weaknesses of their commercial opponents against their competitive advantages, as well as to identify the dispositions and moods of the selective subjects. Due to the strategic choice of when and how to act in the face of market vicissitudes, these companies are called “selective”. |

|

|

3.4. Reputation and brand purpose Finally, as we turn our attention to the regime of adjustment, we realise that marketing gradually understands the importance of neo-hedonistic values, developing and implementing products and advertisements that use them as “alternatives to inconsequential consumption”. We can even think, almost naively, that companies and brands started to establish ways to adjust themselves to the feelings of these consumers and, from the adjustment and sharing of ethical and sustainable values, brands developed greener and more ecological products. On the other hand, we cannot forget that marketing has always known how to appropriate dominant discourses and practices — and even emerging ones — as a manipulative strategy of adoption and consent to bolster its sales and consumption longevity goals. At the most and if that can be said, there could be, in the case of neo-hedonistic consumers, a manipulation by adjustment, in the marketing strategies of companies and brands in this regime of meaning. Among these initiatives, some marketing strategies stand out. Experiential marketing relies on the emotions experienced by customers at all points of contact with the brand, based on responses built in the act of interaction, to convince, engage and, finally, retain their consumers. The interactions of consumers with brands start to be closely observed to understand how these neo-hedonistic consumers experience them and what emotional stimuli are generated in these experiences, preparing the company to respond as best it can in the coming interactions. Green marketing, also known as environmental marketing or eco-marketing, is a marketing strategy that is structured on the benefits — or the absence of harm — that can be introduced into products, in the means of production and in the general purposes of a brand so that it adjusts to the environmental, social, and ethical demands that neo-hedonistic consumers propose. In addition to encouraging the construction of an ethical brand purpose, which occurs through the implementation of an “ecologically correct, economically viable, socially fair and culturally accepted approach”, it is essential that the brand effectively implements an attitude of real transformation that adjusts to the expectations and experiences of its consumers. Just the realisation of an ecological discourse that is not sustained as a brand attitude, however, can be quite negative for the company and for its relationship with neo-hedonists and even with the market in general. This negative practice, known as greenwashing, consists of promoting advertising and communication campaigns about the company’s environmentally correct stance without the effective support of business decisions. We cannot forget the social marketing strategies which, even though they are not a recent practice, correspond to the set of initiatives carried out by a company with social purposes, detaching them from marketing activities, that is, from the need of consuming — at least in that moment. Social marketing is a strategy that associates the brand with a relevant cause for its consumers, in order to connect the company to values that promote mutual benefits for society and for the company. Without initially aiming for commercial results, social marketing strategies help to build the company’s reputation and purpose as a way to bring it closer to its consumers, trying to adjust to the concerns and anxieties that intertwine among its audiences in the market. By seeking to adjust, the company aims for a lasting and meaningful relationship with these consumers, a relationship that, at some point, must be converted into consumption and, perhaps, in loyalty. In the competitive market situation, companies that normally operate in the regime of adjustment, which, as we know, should not be a definitive or lasting position, prefer first to understand the general movements of competitors and then adjust to those that best suit their strategic potentialities, to its products, to its services. These are called “adaptive” companies, which prefer to live in the market taking advantage of their ability to feel the competitive movements and the dispositions and expectations of their consumers, in order to define their ways of operating. |

|

|

From all these observations, we come across the following diagram, which aims to map the regimes of interaction and meaning in the “post”-consumption world22. |

22 Adapted from Landowski’s interactional model. Cf. Interações arriscadas, op. cit., p. 80. |

|

However, the statute of “post”-consumers, as well as the strategic and competitive positions of companies and brands in their post-digital marketing, cannot simply be seen as formal and monolithic configurations, as utilitarian and permanent syntaxes. On the contrary, it is in the movement, in the progression from one regime to the other that the meanings of marketing strategies and living the world of consumption are built. Because they are neither static nor consolidated, the marketing practices that rule the brands’ actions in each one of the interaction regimes, when experienced by the subjects of consumption in everyday interactions (between brands, companies, consumers and the market) allow that their potentialities, their insufficiencies and their limits are apprehended and mastered. It is this domination, enhanced by practice and associated with the permanent search for meaning in pregnant relationships, that leads to the development of dynamics that are interwoven among so many movements that the regimes of interaction make possible.

|

|

References Acar, Yusuf, “Post Consumption”, in H. Babacan and B.C. Tanritanir (eds.), Current Researches in Humanities and Social Sciences, Montenegro, Ivpe Cetinje, 2020, p. 310-325. Bauman, Zygmunt, Consuming Life, Cambridge, Polity Press, 2007. Tr. port. Vida para Consumo : a transformação das pessoas em mercadoria, Rio de Janeiro, Zahar, 2008. Ciaco, João Batista, A inovação em discursos publicitários : comunicação, semiótica e marketing, São Paulo, Estação das Letras e Cores, 2013. Domingues, Izabela and Miranda, Ana Paula de, Consumo de Ativismo, São Paulo, Estação das Letras e Cores, 2018. Fabris, Giampaolo, Il nuovo consumatore : verso il postmoderno, Milan, FrancoAngeli, 2003. Greimas, Algirdas J. and Joseph Courtés, Sémiotique.Dictionnaire raisonné de la théorie du langage, Paris, Hachette, 1979. Tr. port. Dicionário de Semiótica, São Paulo, Cultrix (without datation). Hobsbawn, Eric, The Age of Extremes : 1914-1991, London, Hachette UK, 2020. Klein, Naomi, No logo : taking aim at the brand name bullies, Toronto, Knopf, 2000. Tr. Port. Sem Logo : a tirania das marcas em um planeta vendido, Rio de Janeiro, Record, 2004. Kotler, Philip, Marketing management : millennium edition, New Jersey, Prentice Hall, 2000. Tr. port. Administração de marketing : a edição do novo milênio, São Paulo, Prentice Hall, 2000. Landowski, Eric, Passions sans nom, Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 2004. — Les interactions risquées, Limoges, Pulim, 2005. Tr. port. Interações arriscadas, São Paulo, Estação das Letras e Cores, 2014. — “Sociossemiótica : uma teoria geral do sentido”, Galáxia, 27, 2014, p. 10-20. Lipovetsky, Gilles, Le bonheur paradoxal : essai sur la société d’hyperconsommation, Paris, Gallimard, 2006. Tr. port. A Felicidade Paradoxal : ensaios sobre a sociedade do hiperconsumo, São Paulo, Companhia das Letras, 2007. Perusset, Alain, “L’expérience au cœur du marketing postmoderne”, Acta Semiotica, I, 2, 2021. Semprini, Andrea, La marca postmoderna : potere e fragilità della marca nelle società contemporanee, Milan, Franco Angeli, 2006. Tr. port. A marca pós-moderna : poder e fragilidade da marca na sociedade contemporânea, São Paulo, Estação das Letras e Cores, 2006. Walser, Robert, Selected Stories, New York, Farrar, Straus, Giroux (eds), 1982. Tr. port. Absolutamente nada e outras histórias, São Paulo, Editora 34, 2014. |

|

1 R. Walser, Selected Stories, New York, Farrar, Straus, Giroux (eds), 1982. Tr. port. Absolutamente nada e outras histórias, São Paulo, Editora 34, 2014, pp. 71-73. 2 This reminds the behavior of the undecided thoughtful subject (“le pensif velléitaire”), identified as the one who “wonders to such an extent about his motivations and reasons to act, about what he would like to do, what he should or could do that, in the end, he never really does anything” (our translation). E. Landowski, Interações arriscadas, São Paulo, Estação das Letras e Cores, 2014, p. 43. 3 A.J. Greimas e J. Courtés, Dicionário de Semiótica, São Paulo, Cultrix (without datation), p. 62 4 Cf. entry “consumir” (to consume) in Grande Dicionário Houaiss da Língua Portuguesa, online version, https://houaiss.uol.com.br/corporativo/apps/uol_www/v5-4/html/index.php#6, 02/09/2021. 5 Cf. Y. Acar, “Post Consumption”, in H. Babacan and B.C. Tanritanir (eds.), Current Researches in Humanities and Social Sciences, Montenegro, Ivpe Cetinje, 2020, pp. 310-325. 6 Cf. J.B. Ciaco, A inovação em discursos publicitários : comunicação, semiótica e marketing. São Paulo, Estação das Letras e Cores, 2013. 7 P. Kotler, Administração de marketing : a edição do novo milênio, São Paulo, Prentice Hall, 2000, p. 30 (our translation). 8 Some of these criteria were even organised into psychosocial theories, such as Abraham Maslow’s Theory of the Hierarchy of Needs, widely used in administration and marketing, in which the author ranks five categories of human needs in a pyramid, ranging from the most basic to those of self-fulfillment, in which an individual only feels the desire to satisfy the need for a higher level if the previous one has already been satisfied. Cf. A teoria de Maslow, P. Kotler, op.cit, p. 194-195. 9 See G. Fabris, Il nuovo consumatore : verso il postmoderno, Milan, FrancoAngeli, 2003 10 E. Hobsbawn, The Age of Extremes : 1914-1991, London, Hachette UK, 2020, p. 288 11 Cf. A. Semprini, A Marca Pós-Moderna. Poder e Fragilidade da Marca na Sociedade Contemporânea, São Paulo, Estação das Letras e Cores, 2006, pp. 60-70. 12 Cf. A.J. Greimas and J. Courtés, op.cit., pp. 312-313, entry objeto (object, our translation). 13 Z. Bauman, Vida para Consumo : a transformação das pessoas em mercadoria, Rio de Janeiro, Zahar, 2008, p. 41 (our translation). 14 About the concepts of union and junction, cf. E. Landowski, “Jonction versus Union”, Passions sans nom, Paris, P.U.F., 2004, pp. 57-69. 15 E. Landowski, “Sociossemiótica : uma teoria geral do sentido”, Galáxia, 27, 2014, p. 13 (our translation) 16 Cf. I. Domingues and A.P. Miranda, Consumo de Ativismo, São Paulo, Estação das Letras e Cores, 2018, pp. 57-71. 17 Interações arriscadas, op.cit., p. 79 (our translation). 18 N. Klein, Sem Logo : a tirania das marcas em um planeta vendido, Rio de Janeiro, Record, 2004. 19 For a critical perspective about this point, see, in the present issue, A. Perusset, “L’expérience au cœur du marketing postmoderne”, Acta Semiotica, I, 2, 2021. 20 G. Lipovetsky, A felicidade paradoxal : ensaios sobre a sociedade do hiperconsumo, São Paulo, Companhia das Letras, 2007. 21 Interações arriscadas, op.cit., p. 99. 22 Adapted from Landowski’s interactional model. Cf. Interações arriscadas, op. cit., p. 80. |

|

______________ Mots clefs : consumerism, consumption, marketing strategy, post-consumption, post-digital marketing, regimes of interaction. Auteurs cités : Yusuf Acar, Zygmunt Bauman, João Batista Ciaco, Izabela Domingues, Giampaolo Fabris, Algirdas J. Greimas, Eric Hobsbawn, Naomi Klein, Philip Kotler, Eric Landowski, Gilles Lipovetsky, Ana Paula de Miranda, Alain Perusset, Andrea Semprini. Plan : Introduction : absolutely nothing ! 1. The consumer, marketing, and consumption practices 2. Lifestyles, ways of consumption 2.1. The consumerist and the regularity of consumption 2.2. The activist and the resisted consumption 2.3. The selective and the negotiated consumption 4.4. The neo-hedonist and the shared consumption 3. Marketing strategies, strategies of meaning 3.1. Automation and digital algorithms 3.2. Between probability and randomness |

|

Pour citer ce document, choisir le format de citation : APA / ABNT / Vancouver |

|

Recebido em 06/10/2021. / Aceito em 22/11/2021. |