Derniers numéros

I | N° 1 | 2021

I | N° 2 | 2021

II | N° 3 | 2022

II | Nº 4 | 2022

III | Nº 5 | 2023

III | Nº 6 | 2023

IV | Nº 7 | 2024

IV | Nº 8 | 2024

V | Nº 9 | 2025

> Tous les numéros

Miscellanées : Une sémiotique en mouvement

|

Recalcitrant Interactions : Tatsuma Padoan Publié en ligne le 22 décembre 2021

|

|

|

Much like the fieldwork done by an ethnologist, for the semiotician this work on the text is supposed to be a return, free of preconceived notions, to sources. This comparison can be developed further : much in the same way as a stranger who, settling in a community that is recognizably different, would bring with him an entire store of duly organized knowledge accompanied by a somewhat hypocritical sympathy founded on difference, so the relation of analyst to the text is never innocent, and the naivety of the questions asked is often feigned. This was the beginning of the dialectic process of fieldwork. I say dialectic because neither the subject nor the object remain static. |

1 A.J. Greimas, Maupassant. La sémiotique du texte : exercices pratiques, Paris, Seuil, 1976 ; Eng. trans. Maupassant : The Semiotics of Texts, Amsterdam, Benjamins, 1988, p. xxiii. 2 P. Rabinow, Reflections on Fieldwork in Morocco, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1977, p. 39. |

|

In the first excerpt above, quoted from the “Foreword” of his book-length semiotic analysis of Maupassant’s Two Friends, Algirdas J. Greimas strikingly compares semioticians’ work on texts to the ethnographic work done by anthropologists. Similar to anthropologists and their fieldwork, semioticians may be led to experience their work on texts as a simple and sincere return to original sources. According to Greimas though, this comparison between semiotic analysis and ethnographic work may be further developed, and it can be even inverted respect to its premises. Like the anthropologists who, having moved to a community of “others”, would carry — with a sympathetic but also hypocritical attitude (based on the idea of cultural difference) — a whole “body of accumulated and sifted knowledge”3, semioticians’ relation to their text is never innocent, and the ingenuousness of their questions is rather fictitious. However, the “Foreword” also continues saying that, from time to time, we may be fortunate enough to be rewarded for our efforts, out of proportion to the poor discoveries usually made, when certain facts unexpectedly emerge, which are able to shake our certainties, forcing us to question our ready-made explanations. “This path, strewn with obstacles”, says Greimas, “is perhaps that of all scientific practice”4. In the reflections which I will here present, I wish to continue the comparison suggested by Greimas, between semiotic work on texts and anthropological fieldwork, by pursuing some of its postulates to their ultimate consequences5. It is in fact interesting to notice how the Lithuanian semiotician ends up mentioning some of the typical problems concerning fieldwork, namely (1) diversity or otherness of its object of inquiry, (2) positioning of the researcher in the field (characterised by empathy or hypocrisy, naivety or fiction ?), (3) difference between anthropological and native knowledge, and finally (4) discovery of ethnographic data which may deeply shake our certainties and our models. I will try to explore these problems, hoping that they might help us rethinking, or better, refining the semiotic method. My idea is in fact that semiotics may already have a few instruments able to tackle this kind of questions, and that such instruments may be further sharpened and improved through our analytical work, notwithstanding the form of textuality (ethnographic, literary, or other) we are dealing with6. During my discussion, I will refer to the problem of “textual resistance”, namely the idea that the more semiotic texts are stimulating, the more they force us to reconfigure our own analytical tools. I will rethink this problem in slightly provocatory terms — but certainly fit to describe ethnographic work — using the concept of “recalcitrant subjects”. I will borrow this concept from Isabelle Stengers and Bruno Latour7, according to whom we should turn our attention to objects which are less “domesticated” and more “recalcitrant”. Objects that are able to raise new questions, forcing us to reorganise our instruments and theoretical perspectives. In order to explore these issues, I will draw on my ethnographic fieldwork — conducted over a period of about twenty-four months, and distributed across twelve years (starting from 2008) — within the shugen mountain ascetic group Tsukasako in Katsuragi, central Japan, which is part of the syncretic Shinto-Buddhist tradition called Shugendo, or “The way to master/acquire (Jp. osameru) ascetic powers (Jp. gen)”8. This group, affiliated to the Shingon Buddhist temple Tenporinji on top of Mt Kongo or “Diamond Peak” (1125 m), has been active since 2005. The main purpose of the group is the revival of shugen ascetic practices connected to a particular pilgrimage route — the twenty-eight Lotus Sutra mounds in Katsuragi (Katsuragi nij?hasshuku kyozuka) — which unfolds through almost 120 km across the ancient Katsuragi mountain range9. I will analyse the relational and phenomenological aspects of my ethnographic experience with these Japanese mountain ascetics through the lens of semiotics, using the regimes of interaction formulated by Eric Landowski. Finally, I will try to show how, far from being based on forms of communality and reciprocity without differentiation, ethnography and sociality always involve heterogeneous human and nonhuman actors, and may only emerge from interactions and transactions that are inherently recalcitrant.

1. Two contrastive positions ? I would like to start my discussion from a critical examination of different ways in which the conditions of possibility of doing ethnography in anthropology and social sciences may be conceptualised through semiotics. As defined by Greimas, every scientific discourse constitutes itself as a veridictory doing — an action aspiring to the production of some form of truth — whose object is the construction of a certain referent, and whose aim is to taxonomically organise what it intends to explore10. In anthropology the “referent”, namely a certain culture or society — the object to be re-constructed — is produced through a reorganisation of the semantic microuniverse acquired in the field. A reorganisation made through the perceptive and cognitive categories of the ethnographer. However, there are at least two different ways in which semiotics can look at the conditions, possibility, and limits of ethnographic practice. The first way, closer to phenomenology, may be exemplified by the approach of Jean-Claude Coquet11. In his work on the enunciating instances, Coquet, following Benveniste, draws on the famous essay written by Malinowski for the volume edited by Odgen e Richards The Meaning of Meaning12. This essay, entitled “The Problem of Meaning in Primitive Language”, explored a series of issues, from the definition of language as “mode of action” to the notion of meaning as “active force”, against a philosophical idea of language as mirror-like reflection of thought. It was in this work that Malinowski described for the first time the concept of phatic communion, which was later included by Jakobson in his six communicative functions13. In defining language, and more specifically the practice of gossip among Trobrianders, not as vehicle of information, but as the place where social bonds are constituted, Malinowski wrote : “There is in all human beings the well-known tendency to congregate, to be together, to enjoy each other’s company”14. Coquet interprets this passage in terms of a communion and affective proximity which also invests participant observers in relation to the social group they are studying. Ethnographers would then have the task to convey this experience of physis to the readers of their ethnographies, through the logos of anthropological discourse15. Such reflections place us in front of one of the most difficult anthropological tasks, namely the process of translation, from the field experience to the written ethnography16. The problem of translation, which does not only concern anthropology but every scientific project including the semiotic one, is seen from a quite different perspective by Juri Lotman, whose approach I consider representative of the second way in which semiotics can look at the possibility of ethnographic practice. In an enlightening essay on historical methods, translated in the volume Universe of the Mind, Lotman points out that nowadays in human and natural sciences, from nuclear physics to linguistics, it would be unthinkable to look at scientists as external observers of the objects under study, merely extracting from them some form of absolute objective knowledge17. Every scientific discourse sees the researchers as part of the world they describe. Nevertheless, this does not imply that observing subjects and observed objects play identical roles. Quite the opposite. Lotman thus warns us against the philosophical position proposed by Collingwood, who describes the role of the historian in terms of a subject that should identify himself with the historical figures he is studying. According to Collingwood the historian should re-actualise through his own imagination, the experience of a Roman emperor like Theodosius, and then try to understand the motivations behind his actions18. Such an identification, according to Lotman, starts from Collingwood’s misleading assumption — extreme example of post-Cartesian common sense in which truth shines at the centre “bright as the sun” — that the world of the twentieth-century Englishman was the same as that of Theodosius, and that a bit of imagination and intuition sufficed to fill the historical and cultural gap. To this idea, Lotman opposes a semiotic approach which aims at exposing, rather than concealing, the differences between the two worlds, by describing them in terms of translation from one cultural language to another19. This does not mean totally abstracting researchers from their work, something truly impossible, but on the contrary it implies a recognition of their own presence, involvement, and differential relation to their field of inquiry, being fully aware of how such presence might affect their description20. Together, these two positions — Lotman’s emphasis on the gap between researcher and field, and Coquet’s remarks on the phatic and affective communion between the two levels — could both be considered as accurate descriptions of the role of the ethnographer in the field, although relying on seemingly contrasting ideas. As with the two ways of seeing ethnographic and semiotic work, described by Greimas in our opening quote — either as empathy or hypocrisy, as naivety or simulation — Coquet and Lotman postulate, respectively, the possibility and impossibility of establishing a common experiential ground between researchers and their objects of inquiry. While for Coquet such possibility would be the natural outcome of participant observation — and the translation of this experience to the reader (ad quem) after fieldwork would be the challenge — for Lotman the problem of translation is immediately posed (ab quo) already in the field, since it highlights a gap between researchers and informants. But perhaps the problem of translation could be tackled in another way, allowing us to reconsider these two different positions as perspectives that are not necessarily mutually exclusive. |

3 See E.E. Evans-Pritchard, Witchcraft, Oracles, and Magic Among the Azande, Oxford, Clarendon Press, [1937] 1976, p. 241. It is quite striking that in the same year of publication of Greimas’s Maupassant (1976), Evans-Pritchard added, as an appendix to the reedition of his work on Azande, a careful reflection on ethnographic practice (first published three years earlier on the Journal of the Anthropological Society of Oxford), in which he expressed the same problematic ambivalence of the anthropologist in the field, defined for this reason as a double marginal man (Ibid., p. 243). 4 A.J. Greimas, Maupassant, op. cit., p. xxiii. 5 Acknowledgements : I wish to thank Marilena Frisone for reading and commenting on this work, and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science for providing a grant for this study in 2017-18, during a ten-month fieldwork project based at Osaka University, Anthropology Department (JSPS grant PE16043). 6 In light of frequent misunderstandings about the concept of cultural text in social sciences (see e.g. P. Stoller, Sensuous Scholarship, Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1997), we need to recall here that the semiotic notion of text in Paris School is an analytical construct, referring to any configuration of meaning understood as a mechanism of signification and a process of communication, whose plane of expression may be visual, auditory, olfactory, tactile, verbal, syncretic/multimodal etc. The notion of semiotic text is thus not modelled after the idea of written linguistic texts, and is not based on the concept of cognitive representation (P. Fabbri, La svolta semiotica, Rome and Bari, Laterza, 2005 ; G. Marrone, The Invention of the Text, Milan, Mimesis, 2014). On the contrary, the notion of semiotic text might be more correctly defined as antirepresentational, multimodal and dynamic, insofar as it cuts across any (modern Protestant) representational divide between a supposed interior language and the external world. Semiotic textuality might thus recall more closely the Latin concept of textus “texture, woven fabric, cloth, framework, web”, rather than the idea of written work (T. Padoan, “On the Semiotics of Space in the Study of Religions : Theoretical Perspectives and Methodological Challenges”, in T.-A. Poder and J. Van Boom (eds.), Sign, Method, and the Sacred : New Directions in Semiotic Methodologies for the Study of Religion, Berlin and Boston, De Gruyter, 2021, pp. 193-94). It is nonetheless interesting to notice how current critiques of the concepts of text and discourse, anchored as they are to the idea of “written text” and “mental representation”, often need to cast off or downplay the semiotic dimension of affect, body, action, materiality, etc. (cf. B. Massumi, Parables for the Virtual, Durham, Duke UP, 2002). Such critiques thus end up reinforcing the modern divides they wish to overcome, by entirely removing the domain of discourse, language and communication from their own field of inquiry (the “external social world”), and by thrusting it into the “interiority of human mind”. 7 I. Stengers, “Le dix-huit brumaire du progrès scientifique”, Ethnopsy / Les mondes contemporains de la guérison, 5, 2002, <http://www.ethnopsychiatrie.net/actu/brumaire.htm> (last accessed August 29, 2021) ; B. Latour, “Des sujets récalcitrants”, in his Chroniques d’un amateur de sciences, Paris, École des mines, 2006, pp. 187-189 ; B. Latour, “When Things Strike Back”, British Journal of Sociology, 51, 1, 2002, pp. 107-123. 8 On Shugendo, see the works by Miyake Hitoshi (Shugendo : Essays on the Structure of Japanese Folk Religion, Ann Arbor, The University of Michigan, 2001), Allan Grapard (Mountain Mandalas, London, Bloomsbury, 2016), and the edited volumes B. Faure, M. Moerman and G. Sekimori (eds.), Shugendo : The History and Culture of a Japanese Religion, special issue of Cahiers d’Extrême-Asie, vol. 18, 2009, and A. Castiglioni, F. Rambelli and C. Roth (eds.), Defining Shugendo : Critical Studies on Japanese Mountain Religion, London, Bloomsbury, 2020. In Japanese, see the two volumes by Miyake Hitoshi, Shugendo girei no kenky?, Tokyo, Shunj?sha, 1999, and Shugendo shiso no kenky?, Tokyo, Shunj?sha, 1999. 9 On mountain asceticism in Katsuragi, see T. Padoan, “On the Semiotics of Space in the Study of Religions”, op. cit., pp. 197-209. 10 Cf. A.J. Greimas, Sémiotique et sciences sociales, Paris, Seuil, 1976 ; Eng. trans. The Social Sciences : A Semiotic View, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1990, pp. 15-28. See also A.J. Greimas and E. Landowski, “Les parcours du savoir”, in id. (eds.), Introduction à l’analyse du discours en sciences sociales, Paris, Hachette, 1979 ; Eng. trans. “The Pathways of Knowledge”, in A.J. Greimas, The Social Sciences, op. cit., pp. 37-58. 11 See J.-Cl. Coquet, “Les instances énonçantes”, in Phusis et logos. Une phénoménologie du langage, Vincennes, PUV, 2007 ; It. trans. “Le istanze enuncianti”, in Le istanze enuncianti, Milano, Mondadori, 2008. 12 Cfr. B. Malinowski, “The Problem of Meaning in Primitive Language”, in C.K. Odgen, I.A. Richards (eds.), The Meaning of Meaning, London, K. Paul, Trench, Trubner and Co., 1923 ; now in B. Malinowski, Magic, Science and Religion and Other Essays, Glencoe, The Free Press, 1948. 13 These are, we recall here, the emotive, referential, poetic, phatic, metalingual and conative functions, respectively associated with addresser, context, message, contact, code and addressee (R. Jakobson, “Metalanguage as a Linguistic Problem” [1956], in id., The Framework of Language, Ann Arbor, Michigan Slavic Publications, 1980, p. 81). This formulation, presented by Jakobson in 1956 during his inaugural address as president of the Linguistic Society of America, preceded his more famous essay “Closing Statements : Linguistics and Poetics” (published in T.A. Sebeok (ed.), Style in Language, Cambridge MA, MIT Press, 1960 ; Fr. trans. “Linguistique et poétique”, in R. Jakobson, Essais de linguistique générale, Paris, Minuit, 1963) to which scholars generally refer. 14 See B. Malinowski, “The Problem of Meaning in Primitive Language”, op. cit., p. 248. 15 J.-Cl. Coquet, “Les instances énonçantes”, op. cit., pp. 70-71. 16 Cf. T. Asad, “The Concept of Cultural Translation in British Anthropology”, in J. Clifford and G. Marcus, (eds.), Writing Culture : The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1986, pp. 141-164 ; W. Hanks, “The Space of Translation”, HAU : Journal of Ethnographic Theory, 4, 2, 2014, pp. 17-39. 17 J.M. Lotman, Universe of the Mind, London, I.B. Tauris, 1990. 18 See R.G. Collingwood, The Idea of History, Oxford, Oxford UP, 1986. 19 On the topic of translation from a Lotmanian perspective, see F. Sedda, Tradurre la tradizione. Sardegna, su ballu, i corpi, la cultura, Milan, Mimesis, 2019. 20 J.M. Lotman, Universe of the Mind, op. cit., p. 271. The necessity (and heuristic advantages) of such a recognition is also underlined in post-Greimassian semiotics : see E. Landowski, “Politiques de la sémiotique”, Rivista Italiana di Filosofia del Linguaggio, 13, 2, 2019, p. 11. |

|

2. Perspectival reversals and equivocations When I first started my ethnographic research, I had assumed that the object of my inquiry would be the ritual activities of Japanese ascetics (gyoja or shugenja, also called yamabushi, literally “those who prostrate / take refuge in the mountains”) in the Katsuragi mountains, and that the leading and sanctioning authorities, or Sender actants (Destinateurs) of this inquiry, could only be of strictly academic nature. Such expectation was short-lived, since I understood very soon that the ascetics themselves were carving a specific role for me within their group. One of the problems immediately experienced during fieldwork is that the situation in the field considerably differs from the one usually described in ethnographic manuals21. Notably, the idea of an ethnographic observer, very much present in written ethnographies, ends up being systematically questioned in the field. For example, I was once invited by the ascetic practitioners to participate in a business meeting with representatives of local transport companies. On that occasion they were trying to strike a deal, in order to establish a special bus service for pilgrims who wanted to reach the temple on Mt Kongo from one of the nearby stations. The bus service should have included special Buddhist sutra chanting, and detailed information on their ascetic tradition, besides a reduced ticket fee. My role at the meeting was then framed by the practitioners as that of a foreign scholar who had travelled from Europe to study their specific ascetic tradition, and whose very presence confirmed and enhanced the remarkable value and prestige of their religious practice. |

21 For a classical linear and “top-down” conception of ethnography presented in popular sociological works, cf. M. Hammersley and P. Atkinson, Ethnography : Principles in Practice, London, Routledge, 2007 ; R.M. Emerson, R.I. Fretz and L.L. Shaw, Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes, Chicago, The University of Chicago Press, 2011. For an anthropological critique of this kind of ethnographic approach, see instead J. Spradley, Participant Observation, New York, Harcourt, 1980, pp. 27-29. |

|

If translation can be understood, according to Viveiros de Castro, as a form of “controlled equivocation”, this legitimising role, which I was often invited to play, in some way exposed a first equivocation, namely my initial assumption that I was the one analysing their form of life, and that the ascetics were the object of my investigation22. It was frequently the opposite : the ethnographic work showed how source and direction of agency were constantly reversed. Often, I was the one who was factitively manipulated, the one tested by the group through a series of roles which members of the ascetic community had placed me in23. Such actantial roles ranged from positions of authority — for which I was invoked as Sender (Destinateur), in order to legitimise their specific agenda and instrumental programmes of action24 — to humbler positions within the temple — for which I was reassigned as Helper actant (Adjuvant) in weekly cleaning and in the ongoing maintenance of the place. The latter position of “monastic aid”, in which I frequently found myself, could be actantially assimilated, on the plane of seeming (i.e. from the point of view of what seems to be) to the role of modal helper25. But on the plane of being, this was the role of a performing subject who continued, as the practitioners often told me, a process of apprenticeship that went beyond what was considered, strictly speaking, ascetic ritual activity. Although since the beginning of my fieldwork I felt accepted by the community, on a few occasions, especially in the first period, I also had the impression of being strategically invoked for my status of foreign researcher. This seemed to be confirmed by the numerous circumstances in which I was warmly encouraged to publish, present and translate their world into the academic world, in order to circulate and magnify the image of their group, against other competing ascetic communities. But I soon realised that our relation was going to change according to an ongoing intersubjective process of fiduciary construction26. In fact, my position within the group, and the form of subjectivity offered to me, did considerably change over time, in the same way as my thematic role of “researcher” was also subject to modifications. My historical knowledge of the pilgrimage was often appreciated by members, and it was associated with a form of academic authority. “Can you see it ? Padoan-san knows about it”, “He will meet important scholars, he will talk to them about us”. Somehow, the practitioners started to consider me as their academic alter-ego. Since this was a relatively recent group, they considered themselves as ascetic apprentices. At the same time, members of the group considered me as a young scholar, who proceeded in his life and career in the same way as they were proceeding along the path of ascetic apprenticeship. From their own point of view, the more my anthropological research appeared in the academic community, the more the activities of the Tsukasako would gain visibility both within and without the academic environment. Vice versa, practitioners also thought that the more they became skilled in their practices establishing themselves more firmly within the context of mountain asceticism in Japan, the more my research would become significant. We proceeded across parallel paths, which mirrored each other in a mimetic and somatic way. As Paul Rabinow pointed out in his reflexive analysis of fieldwork in Morocco, ethnographer and informant are often mutually brought to reflect on their own lifeworlds, to objectify and externalise their cultural and social experiences27. From a semiotic point of view, they are doing so by shifting out and observing themselves, thus occupying the two actantial positions of subject and object at the same time28. But in this way, they are also trying to create an in-between space between the two cultural worlds, and a special form of communication. Using the words of Rabinow, fieldwork thus becomes “a process of intersubjective construction of liminal modes of communication”29. |

22 Cf. E. Viveiros de Castro, “Perspectival Anthropology and the Method of Controlled Equivocation”, Tipití : Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America, 2, 1, 2004, pp. 3-22. 23 For a similar amusing case, in which an anthropologist in a Moroccan village is constantly acted upon by his informants, who systematically place him in the role of a driver, using his car to reach the next city almost on a daily basis, cf. P. Rabinow, Reflections on Fieldwork in Morocco, op. cit., pp. 112-115. I wish to thank Eric Landowski for drawing my attention to some interesting common isotopies between mine and Rabinow’s experience. 24 Cf. A.J. Greimas and J. Courtés, Sémiotique. Dictionnaire raisonné de la théorie du langage, Paris, Hachette, 1979 ; Eng. trans. Semiotics and Language : An Analytical Dictionary, Bloomington, Indiana UP, 1982, pp. 245-246. 25 On the modal helper actant, see Ibid., p. 141. Concerning the interplay between “seeming” and “being”, we recall what Greimas and Courtés say about veridictory modalities : “The category of veridiction is constituted [...] by the correlation of two schemas : the seeming / non-seeming schema is called manifestation, the being / non-being schema is called immanence. The ‘truth game’ is played out between these two dimensions of existence. To infer from manifestation the existence of immanence is to make a pronouncement concerning the being of being” (Ibid., p. 369). 26 On the notion of trust, cf. E. Landowski, La société réfléchie, Paris, Seuil, 1989 ; It. trans. La società riflessa, Rome, Meltemi, 2003, pp. 199-214 ; H. Garfinkel, “A Conception of, and Experiments with, ‘Trust’ as a Condition of Stable Concerted Actions”, in O.J. Harvey (ed.), Motivation and Social Interaction, New York, Ronald Press, 1963 ; E.E. Evans-Pritchard, Witchcraft, Oracles, and Magic Among the Azande, op. cit., p. 247. 27 P. Rabinow, Reflections on Fieldwork in Morocco, op. cit., p. 152. 28 A.J. Greimas and J. Courtés, Sémiotique. Dictionnaire…, op. cit., p. 351. 29 P. Rabinow, Reflections on Fieldwork in Morocco, op. cit., p. 155. |

|

Or maybe this was just one more ethnographic equivocation ? The last turning point occurred more recently, when I visited again the same field for a period of about ten months, from March 2017 to January 2018. As soon as I arrived, I could attend the long-awaited official ceremony of initiation (yamabushi tokudo girei), for which the apprentices had been preparing themselves for many years. Immediately, even if I had been participating in the group’s activities for an extended period, I was this time offered a more restricted role within the group, in a position of exclusion, which prevented me from accessing the sacred space of the ritual (which I could only observe from outside), or from performing some mudr? ritual gestures and mantric formulas that only initiates could recite. On top of this, a new highly skilled practitioner had arrived in the group, namely a Buddhist monk who, as an ordained member of the monastic community, second only to the leader, enjoyed a much higher status than mine. The form of academic authority which I had been previously assigned became at this point, in the eyes of the expert monk recently arrived in the community, a possible threat to the religious authority embodied by him and the leader. In a quite systematic way, the new member started to weaken the position of academic Sender which the other believers had placed me in, by ignoring, objecting or dismissing what I was saying, by casting doubts on the legitimacy of my presence within the group, or setting limits to my acquisition of competence in terms of what I “was able” to do, or “knew how” to do. I had wrongly assumed that, after a long period of time spent in the same field, trust would no longer be an issue, but all of a sudden I felt as if I were back to square one : negotiation of trust had to start over again. |

|

|

It is thus rather evident that the process of fiduciary construction, namely the enunciative contract at the roots of every communicative strategy30, is profoundly shaped by the informants, and constantly negotiated by the researcher. This aspect affects the whole research : in place of a semiotic and ethnographic object, constructed by the analyst, what emerges here is, using Isabelle Stengers and Bruno Latour’s words, a “recalcitrant object” which offers resistance31. Or, to be more precise, a full-fledged recalcitrant subject, who does not fulfil our expectations of being observed and analysed, but who instead observes and evaluates us. We thus face a reversal of perspectives. We could in fact describe the two perspectives of the researcher and of the ethnographic subjects as two opposing programmes of action, as an opposition between gazes crossing each other, mutually constructing their own object32. We meet recalcitrant subjects who pursue their own objectives, by framing the researcher within their own programmes of action as Helper actant, or as an authority with the function of Sender actant. Other times, ethnographic subjects may become themselves Senders, and assign to the ethnographer a series of thematic roles and figurative paths. In my own ethnography, these shifted from the role of “academic promoter” to the “foreign ascetic” accepted within the community, and to that of the non-initiated “intruder”, i.e. an anti-subject delegated by an outside academic power, potentially undermining the religious authority inside the group. |

30 On the role of fiduciary contracts in establishing intersubjective structures, cf. A.J. Greimas and J. Courtés, Sémiotique. Dictionnaire…, op. cit., pp. 59-60. 31 Cf. I. Stengers, “Le dix-huit brumaire...”, art. cit. ; B. Latour, “Des sujets recalcitrants”, op. cit. 32 For a detailed analysis of such “optical games”, see E. Landowski, La société réfléchie, op. cit., pp. 113-136. |

|

It is for all these reasons that the emic/etic dichotomy, once used in anthropological theory, always dissolves itself during the ethnographic activity, revealing all its inadequacy as soon as what we called “recalcitrant subjects” start to observe, scrutinise, analyse and evaluate our actions, excluding or including us as they like. All this reinforces the notion that the boundaries of the ethnographic text are each time reshaped by dynamics of “contract” and “conflict”, and that the best way to study our ethnographic subjects is through a process of apprenticeship, under the guidance of the actors and cultural texts themselves, learning to see, as the Malinowskian saying goes, from the native’s point of view33. But if we want to take seriously the actors we are working with34, in order to describe the sense of their actions, we might need to take a step further. |

33 B. Malinowski, Argonauts of the Western Pacific, London, Routledge, [1922] 2002, p. 19 ; cf. C. Geertz, Local Knowledge, New York, Basic Books, 1983. 34 Cf. B. Latour, Pandora’s Hope, Cambridge MA, Harvard UP, 1999, p. 306. |

|

In his programme of redefinition of social sciences, Latour invites to take into consideration objections and resistances presented by social “subjects”, in the same way as physicists, biologists and geologists are already forced to do it for their natural “objects” — hence his suggestion to treat the former ones as “recalcitrant objects”35. However, from the short ethnographic account provided above, it is evident how actors in field, in their interaction with researchers, may play roles better described as “subjects”. The latter statement holds true also in the case of nonhuman actors, particularly when considered from a syntactic and actantial point of view. On this point, we could say that semioticians, art theorists, anthropologists and sociologists have already been studying for some time a series of nonhuman actors — from art works to religious idols, from products of consumption to technologies — as something more than inert “objects” without active roles36. Within this frame of analysis, such entities, as soon as they start playing the role of competent interactants, may be considered as full-fledged syntactic subjects who can intervene and act on other objects or, even, other subjects37. If we thus want to further investigate the problem of recalcitrance, we will also need to ask what happens when those experiencing resistance from other beings, bodies, and entities — ranging from deities and forces who exceed human power, to elements of the everyday material scene — are the informants themselves. In other words, how is the recalcitrance of human and nonhuman actors lived by the ethnographic subjects themselves, in the flow of their everyday interactions ? To explore this issue, it will be useful to refer again to my ethnographic field. During my fieldwork with the ascetics from Katsuragi mountain area, I often noticed how most of the space crossed and lived by them, and particularly the temple area, was invested with prescriptions and interdictions of various sorts. Certain actions, for example, had to be performed in front of a statue representing the esoteric Buddhist deity Fudo Myoo (Skt. Acalan?tha vidy?r?ja) during a fire ritual (Jp. goma, Skt. homa), performed either in the temple hall, or outside. Such actions included the chanting of a series of ritual formulas or mantras from Shingon esoteric tradition, together with other Buddhist prayers — more specifically the Heart Wisdom Sutra (Jp. Hannya shingyo, Skt. Prajñ?p?ramit?h?daya s?tra), a scripture commonly recited in different Buddhist schools in Japan. Those ascetics who had already received initiation were also required to perform specific ritual gestures (mudr?) and whisper powerful mantras in a ritual called goshinbo (“rite of bodily protection”), before and after the ceremony itself. Other participants, including me, “were not able to perform” such prescribed actions, due to lack of ritual competence. In a similar way, during the ritual, the space around the sacred fire was interdicted to non-initiates. This place, located in the inner temple hall, faces the main icon of Hoki bosatsu (Skt. Dharmodgata bodhisattva), considered to be the living material presence of this tutelary numen inside the temple. |

35 Cf. B. Latour, Reassembling the Social, Oxford, Oxford UP, 2005, p. 125 ; id., “When Things Strike Back”, op. cit. 36 Cf. J.-M. Floch, Identités visuelles, Paris, PUF, 1995 ; Eng. trans. Visual Identities, London and New York, Continuum, 2000 ; E. Landowski, “Avoir prise, donner prise”, Actes Sémiotiques, 112, 2009 ; It. trans. “Avere presa, dare presa”, Lexia, 3-4, 2009, pp. 139-202 ; E. Landowski and G. Marrone (eds.), La società degli oggetti, Rome, Meltemi, 2002 ; A. Mattozzi (ed.), Il senso degli oggetti tecnici, Rome, Meltemi, 2006 ; D. Freedberg, The Power of Images, Chicago, The University of Chicago Press, 1989 ; A. Gell, Art and Agency : An Anthropological Theory, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1998 ; M. Augé, Le dieu objet, Paris, Flammarion, 1988 ; It. trans. Il dio oggetto, Milan, Mimesis, 2016 ; A. Appadurai (ed.), The Social Life of Things : Commodities in Cultural Perspective, Cambridge, Cambridge UP, 1986 ; A. Henare, M. Holbraad and S. Wastell (eds.), Thinking through Things, London, Routledge, 2007 ; B. Latour, Reassembling the Social, op. cit. 37Cf. M. Hammad, Lire l’espace, comprendre l’architecture, Limoges, PULIM, 2006 ; It. trans. Leggere lo spazio, comprendere l’architettura, Rome, Meltemi, 2003, p. 115. E. Landowski, “Avoir prise, donner prise”, op. cit. |

|

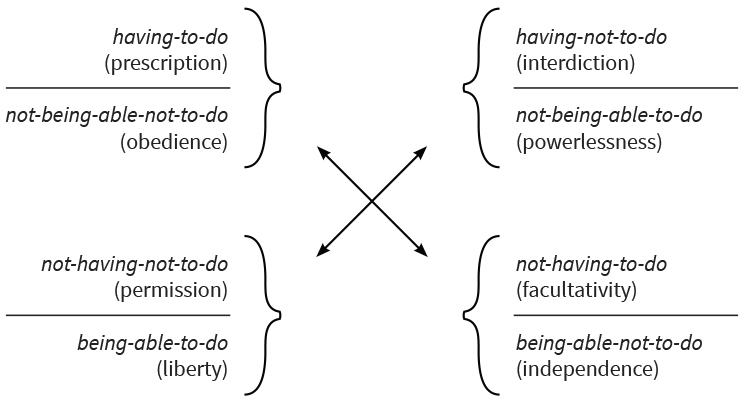

In other words, the ritual scene was strongly modalised from a deontic point of view, as participants, spaces and times of the ritual were overdetermined by a series of “having to do” (prescription) and “having not to do” (interdiction) (fig. 1). These prescriptive and interdicting programmes of action were in turn linked to various degrees of limitation of competence, and thus to what members of the group “were not able to do” (powerlessness of the non-initiated subjects) or “were not able not to do” (obedience of the initiated subjects). This occurred even if both initiated and non-initiated members of the Tsukasako shared a better “knowing how to do”, concerning the ritual tradition, compared to external believers who only visited the temple during major festivals.

Figure 1. Modal structures of obligation (“having to do”) and power (“being able to do”)38. Deontic prescriptions and interdictions were however occasionally accompanied by possible modal negotiations when, under special circumstances, practitioners were allowed to ignore some of them. For example, in the tsukiichikai (“monthly assembly”) — a pilgrimage to sacred places of Mt Kongo, where the temple is located — less experienced practitioners were permitted to guide the group during ritual performances, under the supervision of elder ascetics, while the leader was not attending. In this case, the ritual discourse itself, by opening spaces for the “legitimate peripheral participation” of less expert members, produces an interactive frame of apprenticeship, in which such members can acquire competence, while gradually being included into the group identity39. |

38 A.J. Greimas and J. Courtés, Sémiotique. Dictionnaire…, op. cit., p. 247. 39 Cf. J. Lave and E. Wenger, Situated Learning, Cambridge, Cambridge UP, 1991. |

|

Over numerous sessions of the tsukiichikai, I could see that some elder members “were able not to follow” all the spots of the pilgrimage (assuming the modality of independence), cutting the trail through the forest to skip the hardest parts of the climb. Some other times, the apprentices who made mistakes in choosing the pilgrimage path to follow, or in chanting the ritual sequence of mantras, “did not have to repeat” the pilgrimage or the procedure (on the modal plane of facultativity). In other circumstances we could even “turn a blind eye” to particular prohibitions (and thus a modal permission based on a “not having not to do” something). This happened when an exception was made for me to film the inner hall of the temple during the fire ritual — over the New Year celebrations a few years ago (fig. 2) — or when we “were allowed to see” (liberty) some secret Buddhist icons (hibutsu) usually exposed only during special festivals (called kaicho, or “opening of the curtain”), as a reward for having cleaned and repaired an old ritual building where those were installed40. On several other occasions a rigorous network of injunctions was instead in force.

Figure 2. Filming the fire ritual : the inner temple hall, from interdiction to permission. Courtesy of Tatsuma Padoan. A significant aspect of the practice is that, notwithstanding whether rules could be negotiated or not, their source, that is their Sender actant, was the deity itself, or the leader and elder members as its delegates. Actions like crossing an interdicted space, taking pictures without permission, looking at secret buddhas, or even cleaning sacred effigies with impure cloths and water, were considered as highly disrespectful (shitsurei) against the deity Hoki bosatsu and other “living icons”. Like in the rest of Buddhist traditions in Asia — as documented by ample literature on the topic — such icons are in fact considered as active and concrete sacred presences inside the space of the temple41. |

40 Cf. F. Rambelli, “Secret Buddhas : The Limits of Buddhist Representation”, Monumenta Nipponica, 57, 3, 2002, pp. 271-307 41 Cf. G. Schopen, Bones, Stones, and Buddhist Monks, Honolulu, University of Hawai‘i Press, 1997 ; R. Gombrich, “The Consecration of a Buddhist Image”, The Journal of Asian Studies, 26, 1, 1966, pp. 23-36 ; R. Sharf and E.H. Sharf (eds.), Living Images : Japanese Buddhist Icons in Context, Stanford, Stanford UP, 2001 ; B. Faure, “The Buddhist Icon and the Modern Gaze”, Critical Inquiry, 24, 3, 1998, pp. 768-813. |

|

There is another crucial dimension of the relation between researcher and ethnographic subjects which we have not discussed yet : the role played by the body in the construction of subjectivities. The ascetic practice carried out by the group, which I followed during my participant observation, determines a radical reconfiguration of everyday life, thanks to the intervention of the body. Long walks through difficult and scarcely frequented mountain trails, often fasting or with minimum supplies, while donning the white clothes and equipment of yamabushi ascetics characterised by complex symbolic correspondences ; exhausting night vigils and extended hours spent while singing mantras and Buddhist chants ; fearsome ordeals by fire, walking barefoot on burning coals (hiwatari), with flames reaching up to the knees, etc. All these practices constitute the core of ascetic activity, and they are part of a path of apprenticeship towards the construction of new selves and new worlds. Recalling Coquet’s remarks above, on the phenomenological problem of translating somatic and affective proximity from the ethnographic field to the anthropological discourse, we may wonder : to what extent can ethnographers describe and communicate these modes of experience, so deeply seated within their own body ? André Leroi-Gourhan has pointed out that the suspension of everyday bodily values and rhythms, occurring in religious discourse — e.g. the inversion of day and night-time, fasting, sexual abstinence, variations of temperature — may be used to enact processes of resemantisation and production of new symbolic discourses42. The body and its sensory equipment appear as “a marvellous apparatus for transforming sensations into symbols”43. The networks of symbols thus produced would then introduce a reflexivity in rhythms and values. It is through such networks that religious individuals emerge, reflexively mirroring themselves in symbols and thus constituting themselves as new subjects. Referring to religious traditions he defines as “mystic”, Leroi-Gourhan interestingly suggests that physiological and perceptive modifications may also bring about a symbolic reconstruction of the time and space experienced by practitioners44. A new subject would emerge from such a discourse, a subject characterised by a new role in society and in the universe of values through processes we might define as somatic, or more precisely aesthesic, rooted in perception45. In order to clarify this point, let me recall an ethnographic episode. |

42 Cf. A. Leroi-Gourhan, Le geste et la parole. La mémoire et les rythmes, Paris, Albin Michel, 1964 ; Eng. trans. Gesture and Speech, Cambridge MA, MIT Press, 1993. 43 Ibid., p. 281. 44 Ibid., p. 281-297. 45 I refer here to the notion of aesthesis introduced by Greimas into the semiotic metalanguage (cf. A.J. Greimas, De l’Imperfection, Périgueux, Fanlac, 1987 ; It. trans. Dell’imperfezione, Palermo, Sellerio, 2004) and then further developed by E. Landowski (cf. “A partir de De l’Imperfection”, Passions sans nom, Paris, PUF, 2005, ch. 2 ; more recently, id., “De l’Imperfection : un livre, deux lectures”, Actes Sémiotiques, 121, 2018). |

|

During our long pilgrimage walks, inside the forests across the Katsuragi mountain range, it often happened that, after a few hours of journeying through close-pressing trees, we would find ourselves in an open space. Here we would usually have a short rest. Sometimes we would find a small shrine or statue, in front of which practitioners would pray together. Some other times, however, a wonderful view of a valley, the abundant vegetation of the nearby peaks, or mountain cherry blossoms, could also unexpectedly open below us. On such occasions, we used to stop and contemplate the landscape together, certainly exhausted, and short of breath, but not short of admiration for the spectacular nature surrounding us from every side. The long mountain chain running almost seamlessly from the Wakayama coast in the south-west, up north to Osaka and Nara prefectures, is characterised by low slopes, rounded tops, thick vegetation, frequent watercourses, small waterfalls, and considerable fauna (birds, wild boars, badgers, weasels, rabbits, snakes, foxes, squirrels etc.). On one of these occasions, during the summer of 2017, after a difficult climb, when our energies were about to fade out, we finally reached a natural spring. Following the leader’s instructions, we used our tokin — small black caps worn on the forehead, embodying the five wisdoms of the cosmic buddha Dainichi nyorai — soaked with sweat dripping from our foreheads, to quench our thirst with the freshwater which was generously gushing out from the side of the mountain. After drinking, we all agreed that it really seemed the most delicious water we had ever tasted ! Rarely had I drunk such fresh and clean water, capable of swiftly providing strength and relief. We fully gathered the water with our bare hands, pouring it on our head and shoulders to refresh ourselves, soaking the towel bands (hachimaki) tied around our foreheads, filling our bottles, while a strange sense of excitement started to affect all participants. One of the ascetics noticed that the energising effect of the spring could be related to the mineral salts of our sweat that, drinking from the tokin, we had indeed mixed with the water ! However, this remark did not diminish the euphoric mood of that moment, which, once returned to the city, we did not hesitate to recall and comment upon, while sipping a pint of beer to celebrate the completion of the ascesis. At that point, the religious leader of the group explained that the sensation we felt could only arise after the long climb, a mode of ascetic practice that naturally led us to perceive differently, and fully appreciate, the beauty of the mountain. |

|

|

Such an aesthesic experience of communality — produced by the sensible pleasure we felt, the taste of water and the landscape view — discloses an entire semiotics of perception, in which affective qualities, perceived as immanent in the world, act on the subjects through the mediation of the body. But this could only happen after a somatic and social process of learning had occurred, consisting of intense apprenticeship and ascetic practice46. Recalling the words of Greimas from his book De l’Imperfection : The smell of carnation and the smell of rose are certainly, at once, recognisable as metonymies of the carnation and the rose : with regard to their mode of formation, they are not different from the visual Gestalten “read” by someone who knows a bit about flowers. Yet, hidden under these original designations, perfumed harmonies must unveil their coalescences and correspondences and, through dreadful, exalting fascinations, guide the subject toward new significations produced by intimate and absorbing conjunction with the sacred, carnal, and spiritual. […] Therefore, figuration is not a simple ornament of things : it is that screen of appearance whose virtue consists in disclosing itself, letting others glimpse at itself as a possibility of further sense, thanks to, or because of, its imperfection. The subject’s temperament hence regains the immanence of the sensible.47 The water, its taste, and the landscape perceived by the ascetics, then, while appearing as recognisable Gestalten of the world (i.e. as identifiable figures), simultaneously presented themselves as “imperfect” figures, i.e. open figures that are filled with further aesthesic and affective meanings arising precisely during the process of perception. It is for this reason that the water, its taste, and the landscape, could manifest themselves to the trained ascetics as elements which opened up further possibilities of signification. Water, for example, disclosed its refreshing property, its ability to generate pleasure and energising effects48. It produced a “collective aesthesis” — an intersubjectively shared way of perceiving and feeling — thus presenting itself as much more than mere water. So everybody in the group could notice the shift that occurred when these figures “disclosed” themselves, that is when they presented themselves as more than mere objects, revealing their nuanced properties and affecting the perceivers in various ways, to the point of inverting the initial relationship between subject and object altogether. During this process, defined by Greimas as aesthetic apprehension (saisie esthétique), when time seems to stop, the world overwhelms humans, merging with them49. The affinity with Maurice Merleau-Ponty, quoted by Greimas, is here rather evident, especially if we think about Merleau-Ponty’s notion of “intentional transgression” in Signs. This notion precisely refers to the process through which the ordinary relation we have with objects is reversed, and the latter ones are given the status of “subjects”50. This concept is further elaborated in Merleau-Ponty’s posthumous work The Visible and the Invisible in which, when describing the chiasm and intertwining relation between body and world (a relation that he calls “flesh of the world”), the philosopher even states that “the very voice of the things, the waves, and the forests”51 can itself be conceived as the language of a world that speaks to us. |

46 Cf. E. Landowski, “L’esthésie comme processus et comme apprentissage”, Passions sans nom, op. cit., pp. 153-158. 47 De l’Imperfection, op. cit., p. 58. Cf. C. Segre, “The Style of Greimas and Its Transformations”, New Literary History, 20, 3, 1989, pp. 679-692. 48 For another ethnographic case in China, in which tasting the water is considered as a far more dangerous activity for the fieldworker, related to trance and spirit possession, see J. DeBernardi, “Tasting the Water”, in D. Tedlock and B. Mannheim (eds.), The Dialogic Emergence of Culture, Urbana and Chicago, University of Illinois Press, pp. 179-197. 49 De l’Imperfection, op. cit., pp. 30, 45. On the notion of “aesthetic apprehension” (saisie), cf. also J. Geninasca, “Le regard esthétique”, La parole littéraire, Paris, PUF, 1997 ; E. Landowski, “La rencontre esthétique”, Passions sans nom, op. cit., chap. 5. 50 Cf. M. Merleau-Ponty, Signes, Paris, Gallimard, 1960 ; Eng. trans. Signs, Evanston, Ill., Northwestern UP, 1964, p. 94. 51 Cf. M. Merleau-Ponty, Le visible et l’invisible, Paris, Gallimard, 1964 ; Eng. trans. The Visible and the Invisible, Evanston, Ill., Northwestern UP, 1968, p. 155. |

|

In Alessandro Duranti’s recent book The Anthropology of Intentions, an in-depth re-examination of Husserl’s philosophy, we also find out that the German phenomenologist’s position — described in the unpublished works recently made available in his Nachlass, and consisting of a vast number of lecture notes and manuscripts saved from the Nazis after his death in 1939 — very closely resembled some of the ideas presented many years later by Merleau-Ponty52. In these scripts Edmund Husserl describes for example how the objects “out there” exert a specific affective pull on subjects, and how, during the mutual constitution of self and world, the fundamental role in the construction of Ego is in fact played by the Other53. |

52 Cf. A. Duranti, The Anthropology of Intentions, Cambridge, Cambridge UP, 2015. 53 Cf. E. Husserl, Analyses Concerning Passive and Active Synthesis : Lectures on Transcendental Logic, trans. A.J. Steinbock, Dordrecht, Kluwer, 2001, pp. 196-197 ; quoted in A. Duranti, The Anthropology of Intentions, op. cit., p. 29. |

|

The forms of ethnographic encounter I described in the previous chapters are by no means peculiar to the case I investigated. These modes of experience are instead commonly found in the field and in anthropological literature. A good example is provided by Rabinow’s work quoted above, in which the anthropologist tries to analyse the ethnographic process itself, through a detailed account of the interactions he had with his informants in Morocco while collecting data for his PhD dissertation54. Besides providing a narrative characterisation of his main informants, he reflexively describes how his own relationship with them changed over time, together with the evolving circumstances of his fieldwork. In doing so, he presents an account of his encounter with the ethnographic other, and of the production of anthropological knowledge through a mutually constructed ground of experience, involving both the informants and the researcher. |

54 P. Rabinow, Reflections on Fieldwork in Morocco, op. cit. |

|

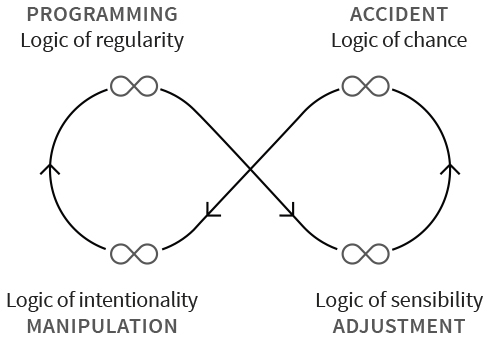

Some of the scenarios Rabinow describes are strikingly similar to the ones I analysed above. The villagers from Sidi Lahcen, strategically using his presence there to enhance their lineages and factions or persuading him to drive them daily to the main city Sefrou for their personal business, are described as acute observers. They continuously test the ethnographer and negotiate their relationship with him, either including or excluding him from their activities, cooperating with him or trying to exert a relation of power. The way informants situate his position in the field, and react to his own reactions, not only determines the ethnographer’s access to knowledge, but also reveals something about the nature of social interaction itself. Interestingly, Eric Landowski has attempted to analyse the scenarios described by Rabinow in his book, according to a model of semiotic regimes of interaction he proposed in other publications55. Landowski describes four regimes, each corresponding to a different logic of interaction (fig. 3).

Figure 3. Regimes of interaction56. These semiotic regimes are : programming, based on a logic of regularity ; manipulation, based on the logic of intentionality ; accident, based on a logic of chance ; and finally adjustment, based on sensibility. In the regime of programming, interactions between actors are stipulated according to certain patterns and courses of action expected or actualised, trying to reduce as much as possible the risk of uncertainty, but also producing a desemantisation of everyday life through routine. People and things are interpreted, controlled and approached according to plans, operations and expected outcomes, and such regularity of events is achieved through repetition, by following a certain script or playing fixed roles57. |

55 E. Landowski, “L’épreuve de l’autre”, Sign Systems Studies, 34, 2, 2006, pp. 317-338. 56 Adapted from E. Landowski, Les interactions risquées, Limoges, Pulim, 2005 ; It. trans. Rischiare nelle interazioni, Milan, FrancoAngeli, 2010, p. 92. 57 Ibid., pp. 17-22. |

|

A second regime, manipulation, characterises modes of interaction in which actants try to impose their own system of values on the others, through adulation, intimidation, deception, provocation, seduction, persuasion, promise, etc., in order to affect their courses of action. By acting as, or evoking, a certain Sender, an actor may use his or her authority, or offer a certain object, to convince their interlocutor to do something for them, or to accept a certain state of affairs. In the same way, a sorcerer can bend a deity to his own will, or trick a demon to chase him away, by performing magical ritual actions or powerful formulas, thus manipulating forms of nonhuman agency. Manipulation acts on the modal competence of the others, along the lines of intentionality, and using strategic forms of rationality which work in intersubjective and often mutual ways58. |

58 Ibid., pp. 22-27. |

|

The third regime, accident, focuses on chance as main rationale. Here interaction with the human or nonhuman other escapes from the predictability of the programming regime, and from the control of the manipulation regime. Relations and events are completely unexpected and beyond regulation, and the only thing we can do is to accept what happened, even if absurd, chaotic or above our comprehension. Contrary to the lessening of meaning provided by void repetition and obsessive planning, here meaning might be way too much to handle. Whether it is blind fortune or a terrible destiny which knocked on our door, we can however take the chance and entrust ourselves to the open possibility of the unknown. This regime might thus represent pure risk, but also a meaningful break from an empty routine59. |

59 Ibid., pp. 63-85. |

|

The final and fourth regime, adjustment, directly involves the body and sensibility of actors in mutual interaction. Like in a dance, in war, in love, when riding a horse, using a tool or engaging in some artistic activity, we often need to dynamically attune to the moves, the rhythm, pace, force, intensity, and material and bodily presence of an entity we do recognise as an interactant, even when its nature seems to be purely mechanic60. To draw from a classic anthropological work, such is the case of the car described by Lévi-Strauss in La Pensée sauvage : The American Indian who deciphers a trail by means of imperceptible clues, or the Australian who unhesitatingly identifies footprints left by a random member of his group (Meggitt) does not proceed any differently than ourselves do when we are driving a car and judge from a single glance, a slight shift in the direction of the wheels, a fluctuation of engine speed, or even from the supposed intention of a look, the moment to pass or avoid another vehicle. However incongruous it may seem, this comparison is rich in instruction ; for what sharpens our faculties, stimulates our perception, and gives assurance to our judgments is, on the one hand, that the means at our disposal and the risks that we run are incomparably augmented by the mechanical power of the engine, and, on the other hand, that the tension that results from feeling this embodied power is exercised in a series of dialogues with other drivers whose intentions, the same as our own, are translated into signs that we constantly strive to decipher because, precisely, these are signs, and call for intellectual effort. […] And it is in fact beyond them in that it entails a confrontation, not exactly between either men or natural laws, but between systems of natural forces humanized by the intentions of drivers, and men transformed into natural forces by the physical energy of which they are the mediators. […] The beings involved confront each other simultaneously as subjects and as objects, and, in the code they employ, a simple variation in the distance separating them has the force of a silent adjuration.61 The car described here is not perceived as an inert or passive object, but as an active force that confronts the driver and interacts with him or her, in a process of mutual adjustment. This process is based on perceptive qualities, sensibility, and the bodily feeling of forces and tensions which affect both the parties involved. Humans and the world do not only mirror each other through a reciprocity of perspectives, but they actually transform each other — the man into natural forces and the car into human extension — creating a tension that arises from “feeling this embodied power”. Such somatic tension has the effect of sharpening the sensory faculties, adjusting the interactants’ position to imperceptible clues, slight turns, fluctuations in movements, glances and looks, in other words to signs (or better moves62) embodied and interpreted by human and nonhuman actors. |

60 Ibid., pp. 47-62. 61 C. Lévi-Strauss, La Pensée sauvage, Paris, Plon, 1962 ; Eng. trans. Wild Thought : A New Translation of La Pensée sauvage, Chicago, The University of Chicago Press, 2021, p. 250-251. 62 According to Landowski, whereas a “sign” has a meaning that stems from some predefined code, permitting its “reading”, an embodied “move” makes sense, a sense which is to be immediately “grasped” among sensitive interactants, regardless of any precodified system. Cf. E. Landowski, “Structural, yet existential” (IV.2. Regimes of meaning in the interaction), in E. Tarasti (ed.), Transcending Signs, Berlin, Mouton-de Gruyter (forthcoming). Cf. a similar interpretation provided by Tim Ingold about the notion of clue, in T. Ingold, The Perception of the Environment, London, Routledge, 2000, pp. 20-22. However, see also Paolo Fabbri’s reinterpretation of signs as affective forces — “a thymic variation, a variation of tension and relaxation within the text” — or in a more Spinozian way, as “effects of actions on bodies, bodies acting on other bodies” (P. Fabbri, La svolta semiotica, op. cit., p. 97). |

|

If we now reconsider the ethnographic descriptions presented in the previous chapters, we can recognise different scenarios of interaction, possibly related to these semiotic regimes. To my eagerness to apply field research methods to the study of a community of ascetic practice, and to my initial ‘objective’ stance in approaching them — an attitude we could connect to the programming regime — the ascetics immediately responded with modes of interaction we could analyse in terms of manipulation. Making me play different actantial positions and thematic roles ; strategically using my status of foreign academic ; deflecting my intentionality towards the enhancement of their prestige : these were only some of the manipulations of my modal competence, which I had to renegotiate in the field. At the same time, the regimes of interaction above could be observed not only in the relation between ethnographer and practitioners, but also among the practitioners themselves, and in the relation between ascetics, ritual space, and deities. While ritual activity was often presented and learnt by practitioners in terms of repetition of actions, and regularity in following certain patterns and procedures (Jp. saho) — according to programmes of ceremonial action — the application of such programmes often involved an interaction with deities who acted upon the modal competence of the ascetics. The latter mode of interaction with nonhuman actors presented all the characteristics of a manipulation, which affected the courses of action of the practitioners through a modalisation of space. Access and ritual use of space were thus regulated by Hoki bosatsu and other deities through deontic interdictions, prescriptions, permissions, etc., according to the degree of power and knowledge shared by the ascetics. |

|

|

Moreover, the ritual training of the practitioners during the tsukiichikai sessions, as described above, included frequent oversights and unpredictable mistakes in the ritual procedure, thus often falling into a logic of chance63. This regime of accident was normally accepted by elder ascetics as part of the training itself. However, it was also counterbalanced by a bodily readjustment of the practitioners to the new situation. When events went off the script, the ascetic apprentices always tried to follow the ritual procedure, even in an imperfect way through progressive attuning, in order to get the ritual done. The latter regime of interaction, which we called adjustment, was governed by a logic of sensibility of the apprentice towards the other participants and the material environment. But it was also closely connected to the notion of mi ni tsukeru (“learning through the body”), which was often discussed by the practitioners as the best way to learn and master (Jp. osameru) ascetic powers (Jp. gen). Also the experience of tasting the water and perceiving the landscape described in the previous chapter, offers a good example of adjustment regime. The somatic training of the ascetic form of life produces a particular mode of experience based on perceptive qualities and bodily mediation of meaning. These affective and aesthesic dynamics are often presented by the ascetics as transcending both the individual and the human, insofar as they are intersubjectively shared between the group of ascetics, the landscape, as well as the deities and ancestors who inhabit it. In the case of the collective and affective experience I described, as with the relation between the car and the driver analysed by Lévi-Strauss, natural world and ascetics seem to inform each other, to mutually adjust according to a logic of sensibility. This mode of interaction is based on a particular way of perceiving the environment and the relation between humans, of “grasping” their “sense” (as opposed to hypothetically reading their meaning). The work on the bodies through fasting and walking in the forest, has in fact the effect of re-motivating bonds within the group and its connection to a semiotics of the natural world. An interesting aspect of these semiotic regimes is that, besides describing a passage from one mode of interaction to another, each of the regimes may contain all the other logics. This mechanism of recursivity is shown in figure 3 by the presence of the infinity symbol inside each of the four sections. Although a certain regime, like for example the one of accident, defines an overall trend emerging in that mode of interaction (based on chance), the other logics (sensibility, regularity, and intentionality) may be virtually present in the situation where such interaction occurs, and may be actualised by the actors involved, modulating the regime in different ways. The arrival of the highly skilled monk in the group may well have thwarted my expectations — when he limited my access to the field and downplayed my presence in the group as a researcher. However, such unpredictable event that we could associate with the regime of accident, was also characterised by a logic of intentionality, insofar as the monk was acting as a Sender for me and the members of the community. And although I had to negotiate again my presence in field, I was ultimately sympathetic to him, adopting a logic of sensibility towards his reasons, as this event opened the chance for me to reflexively analyse my own position in relation to the dynamics of authority within the group. However, perhaps one of the most striking elements of all these interactions, as they emerge from ethnographic experience, is their inner recalcitrance. We understood recalcitrance as a particular quality of the human and nonhuman actors we are working with, which brings us to question our own theoretical and methodological assumptions, and brings the ethnographic subjects themselves to rearrange their own systems of values and conventional sense of reality. This is certainly present in the regime of accident, whose logic of chance and unpredictability unsettles our expectations. The example of the monk, who suddenly forced me to renegotiate trust with the group, well illustrates this point. Moreover, recalcitrance may also be found in the manipulation and programming regimes, in which subjects try to alter each other’s values, intentionality and courses of action, or try to apply regularities to their behaviour, often finding resistance to this. My participation in business meetings, requested by the community of ascetics, or the difficulty in following the ritual format experienced by apprentices, respectively show the recalcitrant ability of the informants to divert the somehow manipulative intentionalities of the researcher, and the recalcitrance of ritual apprenticeship as programmed repetition, which aims at transforming the participant. But perhaps one of the modes of interaction which most epitomised recalcitrance was, in my fieldwork, the regime of adjustment. The bodily experience of pilgrimage, chanting, attending night vigils, fasting and walking on fire, intends in fact to deeply reconfigure the practitioners’ world, through the construction of new values and forms of subjectivity, based on harmonisation and reciprocal transformation between them and the sacred environment of local gods (kami) and buddhas. It was the recalcitrant character of my process of adjustment to ascetic practice, that forced me to reconsider the limits of my bodily resilience and endurance. Because of this, I started focusing on my own body as a living, experiential laboratory of semiotic analysis, for an understanding of the phenomenon called asceticism, and of ethnographic practice more in general. |

63 For a different interpretation of mistakes, slips of the tongue, and inexperience, based on the enunciation of an actant-body, see also J. Fontanille, Séma & soma. Les figures du corps, Paris, Maisonneuve et Larose, 2004 ; It. trans. Figure del corpo, Rome, Meltemi, 2004, pp. 45-124. |

|

What needed to be described in semiotic terms was thus the process of learning triggered by my own encounter with the field and the cultural texts. This process of apprenticeship unfolded through a series of translations situated at the microphysical level of experience, in the small adjustments through which I explored a particular form of life, the ascetic one64. These adjustments had the effect of considerably reducing the significance given to a form of subjectivity conceived a priori as human. The ascetic, in fact, renounces the self or, more precisely, he or she actually discovers that the self is a multitude65 , a network that connects rather than divides humans, gods, places and discourses of the natural world. |

64 On the semiotic notion of “form of life”, see C. Zilberberg, “Le jardin comme forme de vie”, Tropelias. Revista de Teoria de la Literatura Y Literatura Comparada, 7-8, 1996 ; It. trans. “Il giardino come forma di vita”, in Giardini e altri terreni sensibili, Rome, Aracne, 2019, pp. 39-64. 65 Cf. G. Simondon, L’individuation psychique et collective, Paris, Aubier, 1989 ; It. trans. L’individuazione psichica e collettiva, Roma, DeriveApprodi, 2001. |

|

6. Learning from recalcitrance 6.1. Translation as apprenticeship At the beginning of this article we discussed two contrasting positions, respectively presented by Coquet and Lotman, concerning the relation between researchers and their field of inquiry. These two points of view were connected to different semiotic understandings of how ethnographic work may be conducted in anthropology and social sciences. According to Coquet, one of the main tasks of the ethnographers would be to translate and convey the affective and bodily experience (physis) they shared with their ethnographic subjects on fieldwork, into the reflexive language (logos) of ethnographic writing66. But such a translation of physis into logos, or somatic experience into language, presupposes that, before this process of inscription occurs, a common experiential field should already be established between ethnographers and informants — an intersomatic phenomenological ground in which the same perceptions and emotions may be felt and shared among all the parties involved. |

66 However, we need to be careful before creating misleading hierarchies between fieldwork and deskwork (cf. B. Mannheim and D. Tedlock, “Introduction”, in D. Tedlock and B. Mannheim (eds.), The Dialogic Emergence of Culture, Urbana and Chicago, University of Illinois Press, pp. 2, 18). We might argue in fact that somatic physis and discursive logos are both present in fieldwork, intertwined together with different degrees of entanglement. |

|

Such a common experiential ground is instead questioned by Lotman. His perspective, as we already noted, intends to show how ethnographers and informants inevitably start from different planes of social and cultural reality, urging us to consider how the presence of the researcher in the field affects the investigation. Rather than obliterating differences between fieldworker and informants, Lotman invites us to expose them, analysing the gap between the parties involved in terms of a process of translation between cultural languages. Therefore, while, according to Coquet, the process of translation mainly occurs ad quem, i.e. afterwards between author and readers, according to Lotman it would already start ab quo, from the beginning of the fieldwork, between the scholar and the informants. The latter idea also characterised Rabinow’s account of his fieldwork in Morocco, in which the growing and shifting relations established between himself and his informants became the core of his investigation. As we have seen in my ethnographic account of Japanese mountain ascetics, such relations emerging in the field often involve power, authority, hierarchy and asymmetrical distribution of agency. |

|

|

We should however recall what Gilles Deleuze wrote in his book on Foucault : “Power-relations are the differential relations which determine particular features (affects)”67. In other words, differential relations involving power, authority and asymmetry do not necessarily prevent the construction of a common affective field. As we have seen in our analysis of aesthesis (modes of perception) and affect in ascetic experience, differential relations become the ground upon which such a field may be actualised. Differences with recalcitrant subjects of various kind and appearance, from demanding ascetics and belligerent monks, to deities sometimes uncompromising, sometimes permissive — without forgetting the relation with another form of otherness, the mountain itself and its particular sensory semiotics — all such differences are to be translated by ethnographers, through a process of learning. We might argue in fact that in ethnographic fieldwork, all differences are necessarily translated through our bodily experience, and that such a process of translation consists in a form of apprenticeship. It is no wonder that one of the great masters of ethnographic work, Edward E. Evans-Pritchard, had already recognised the fundamental role played by the process of learning in fieldwork (“you are their pupil, an infant to be taught and guided”68), and the huge impact this process has on the ethnographer’s subjectivity (“[anthropologists are] transformed by the people they are making a study of”69). The act of translating differential relations in the field may thus be conceptualised as a process of apprenticeship under the guidance of the ethnographic actors, learning to see from their point of view. The fact of being continuously acted upon by other ascetics, deities, and by the mountain environment, not only moved me from the position of an observer (and sanctioning Sender) to the one of the observed (and sanctioned Subject), but also produced another curious perspectival inversion. As argued by Marc Augé in his book on Oblivion, we could talk about a sort of methodological reversal, in which questions are no longer posed by the analyst, but by the ethnographic actors themselves70. How to analyse such a change of perspectives and agencies, which characterises the way we translate differences in the field by learning from our human and nonhuman informants, always trying to control equivocations which inevitably arise ? We tried to do so by looking at the shift of actantial positions played in the field, in different regimes of interaction with practitioners and deities — accidents, manipulations, programming, and adjustments — which triggered dynamics of inclusion and exclusion from the field itself. We thus conceived the field as a semiotic text whose boundaries are constantly negotiated by fieldworker and informants through these regimes, and through a process of fiduciary construction, i.e. the intersubjective construction of trust. But we also saw that an important role in this analysis was played by the recognition of spatial modalisations investing ritual actions, and generated by sacred deities. Deities were considered as the main source of interdictions and prescriptions for both ethnographer and practitioners, although facultativity and permission could also be negotiated and granted during a process of ritual apprenticeship which inevitably involved approximations, errors, and adjustments. |

67 G. Deleuze, Foucault, Paris, Minuit, 1986 ; Eng. trans. Foucault, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1988, p. 75. My reading of Deleuze considerably differs from Brian Massumi’s interpretation (in Parables for the Virtual, op. cit., pp. 23-45) and from other contemporary anthropological reflections which tend to divide “affect” from discourse (C. Hirschkind, The Ethical Soundscape, New York, Columbia UP, 2006 ; K. Stewart, Ordinary Affects, Durham, Duke UP, 2007 ; Y. Navaro-Yashin, The Make-Believe Space, Durham, Duke UP, 2012). Such views reinforce a modern Protestant ideology of separation between an interior language, now located in the cognitive paths of the mind, and an external world, associated with bodily perception, materiality and affect (cf. W. Keane, Protestant Moderns, Berkeley, University of California Press, 2007 ; R. Bauman and C. Briggs, Voices of Modernity, Cambridge, Cambridge UP, 2003). However, we might argue that Massumi’s notion of the autonomy of affect from discourse, does not come from Deleuze but from the projection of this semiotic ideology (or episteme) which has become particularly influential in Anglo-American scholarship. Rather than being pre-semiotic, for Deleuze and Guattari corporeality and affect are in fact part of a “presignifying semiotic” (G. Deleuze and F. Guattari, Mille plateaux, Paris, Minuit, 1980 ; Eng. trans. A Thousand Plateaus, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1988, p. 117), and “a semiotic chain is like a tuber agglomerating very diverse acts, not only linguistic, but also perceptive, mimetic, gestural, and cognitive […]. Language is, in Weinreich’s words, ‘an essentially heterogeneous reality’” (Ibid., p. 7). 68 E.E. Evans-Pritchard, Witchcraft, Oracles, and Magic Among the Azande, op. cit., pp. 253-254. 69 Ibid., p. 245. 70 Cf. M. Augé, Les formes de l’oubli, Paris, Payot, 1998 ; Eng. trans. Oblivion, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2004, p. 24. |

|