Derniers numéros

I | N° 1 | 2021

I | N° 2 | 2021

II | N° 3 | 2022

II | Nº 4 | 2022

III | Nº 5 | 2023

III | Nº 6 | 2023

IV | Nº 7 | 2024

IV | Nº 8 | 2024

V | Nº 9 | 2025

> Tous les numéros

Miscellanées : Une sémiotique en mouvement

|

Pragmatics and Semiotics Per Aage Brandt Publié en ligne le 22 décembre 2021

|

|

|

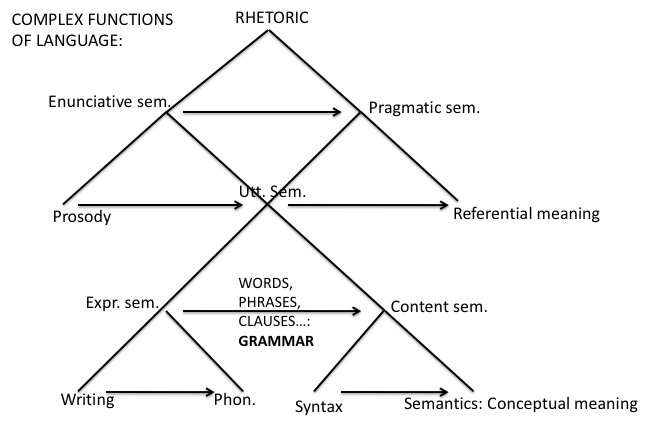

... the only way out is through the formulation of a general Pragmatics, as well as semiotics, may be described as a discipline studying meaning and language. A possible way of distinguishing these disciplines would be to let pragmatics be the study of expressed meaning in a context of pragma, while semiotics takes care of the internal syntax and semantics of expressed meaning, or in other words, to understand semiotics as the study of the immanent aspects of meaning, and pragmatics as the study of its transcendent aspects2. If meaning only had transcendent aspects, in this sense, pragmatics would be semiotics, and inversely. However, that view presupposes, as the French-Lithuanian semiotician A.J. Greimas says (in the quotation above), a general theory of language, and thus a theory of the general architecture of existing aspects of expressed meaning3. In this respect, our discussion necessarily involves linguistics. What would an immanent-transcendent model of the componential structure of language look like ? To answer this question would be to describe the relations between semiotics and pragmatics, and it would yield a view of a more comprehensive discipline that, so far, has no name. A semio-pragmatics ? We will venture to draft a version of such an answer by presenting a general model of language in its structure and in its use.

1. Modelling the relation between pragmatics and semiotics The first such model is based on the notion of semiosis. A semiosis is a “little machine”, some say a “coded” function, that makes an expression refer to something, its “content”4. As Louis Hjelmslev ((1943), 1993) and, after him, Roland Barthes (1985) suggested, expressions and contents can also each be entire semiosis5 ; so, one semiosis can be the expression of, that is, connote, another semiosis6. And it can be the content of another semiosis, as a text in a painting7. Language can be described as an inter-semiosic agglomeration of these little semiotic machines, an inter-semiosic architecture. This is what the model shows (fig. 1, below)8. Let us take a look at the composition of this inter-semiosic model of language. The most conspicuous of the involved semiosis is the one that makes phonetic strings, as expressions, refer to grammatical meanings, as their contents ; these strings can be morphemes, words, phrases, clauses, sentences, entire texts, in so far as they have phonetic properties. The lexical, grammatical, and discursive meanings are the meanings thus conveyed. Furthermore, phonetics is itself a semiosis since the involved bodily, substantial expressions (writing, gesture, phonation) mean the formal phonemes and syllables that are the linguistic expressions. And the syntactic meaning of the resulting linguistic expressions, that is, of the words, phrases, clauses, sentences, and trans-phrastic units, which all have conceptual meaning to contribute, is a linguistic semantics. Therefore, at the core of linguistic immanence, we have a general grammatical semiosis of two semiosis, the phonetic semiosis and the semantic semiosis. The bodily “input” (phonetics) is grammatically connected to a mental “output” (semantics) of this process, namely what we call conceptual meaning. Conceptual meaning exists in different formats, of course : from single concepts to entire stories or doctrines. However, this triple semiosis — phonetics-through-grammar-to-semantics — producing conceptual meaning has to be inserted in an equally complex transcendent superstructure in order to give rise to what we are especially interested in here, namely referential meaning, i.e. meaning as we experience and understand it in context. Conceptual meaning has to be converted to referential meaning, as semantics feeds into pragmatics. |

1 A.J. Greimas, “Pragmatics and Semiotics. Epistemological Observations”, in P. Perron and Collins, Paris School Semiotics, Amsterdam, Benjamins, 1989, p. 93. This was read as an introductory lecture to the International Symposium on Pragmatics and Semiotics held at the University of Perpignan the 17-19th November 1983. 2 An example : The concept of justice means different things in the (transcendent) context of revenge or retribution and in that of jurisdiction. In itself, immanently, it contains a schema of balance or equilibrium between “weights” of penalty and wrongdoing. 3 Meaning is expressed in many ways, and language is only one of them, although presumably predominant. The realm of available expressive activities in the human world is extensive. For example, there are certainly reasons for developing a pragmatics of music, as of the vast family of iconic media and symbolic gestures and objects (think of architecture). Nevertheless, it may be wise to start out by considering language in particular ; very few of the other forms would have evolved without it. 4 The function that ties a content to an expression, or a signified to a signifier, is an automatic mental mechanism, not a process of reasoning like the interpretation of a treatise of philosophy ; I use the diagrammatic format of a triangle for a semiosis so that the “coding” mechanism can occupy an angle. This “little machine” is a cognitive routine intimately related to the neural processes that make us think. We do not know yet what they are and how they causally work, but we can approach them by observing as closely as possible what they are achieving : the different forms of meaning-making that pervade the human world. 5 Cf . L. Hjelmslev, Prolegomena to a Theory of Language, Baltimore, Indiana University Publications, 1943. R. Barthes, L’Aventure sémiologique, Paris, Seuil, 1985. 6 The principle of semiosic recursion is presented in P.Aa. Bandt, “The Sign Cascade. A Basic Format of Semiotic Apperception”, in B. Fraser and K. Turner (eds.), Language in Life, and a Life in Language : Jacob Mey. A Festschrift, Bingley (UK), Emerald, 2009. A broader unfolding of this glossematic discovery may be found in P.Aa. Bandt, “From Linguistics to Semiotics : Hjelmslev's fortunate Error”, in A. Hénault (ed.), Le sens, le sensible, le réel. Essais de sémiotique appliquée, Paris, Sorbonne University Press, 2019, has. 7 Hjelmslev called this constellation a relation between a metalanguage and its object-language. The “meta-semiosis” that has an “object semiosis” in its content is rather the context of the embedded semiosis. This constellation is therefore of great interest to pragmatics as a study of contexts. 8 The model is explained in the chapter “The Role of Semio-Syntax”, in P.Aa. Brandt, The Music of Meaning. Essays in Cognitive Semiotics, Newcastle upon Tyne, Cambridge Scholars, 2019. |

|

In order to understand this wider framework, we first need to introduce the semiotic component of enunciation (from Benveniste9). Enunciation is a semiosis, whose “little machine” lets certain expressions indicate states and attitudes of speaker's and hearer's subjectivity, social identity, and condition. The simplest manifestations of enunciation in language are the systems of personal pronouns and the deictic forms (demonstratives, shifter adverbs, etc.) that languages use. The dimension we call prosody superimposes enunciational meanings onto the immanent linguistic semiosis. These meanings include speaking from a higher or lower status than the hearer’s ; speaker and hearer knowing or not knowing each other ; gender and gender difference ; generational difference ; and (personal or social) emotional tonality. The enunciational semiosis overdetermines all utterances uttered, and the result is then transposed into situational meaning through a specific pragmatic component that takes the personalised utterances as appropriate signifiers and the specific situation as signified. This pragmatic component is a semiosis, in the sense that it makes the personalised utterances mean their situational context, contribute actively and intentionally to making the context specific and, in this respect, meaningful. Contexts become meaningless if we do not “intend” them by letting our language signify them. Ceremonial rituals become invalid if the formulaic language they involve is not displayed appropriately ; conversations are not taking place if our utterances do not “converse” in the right way (lecturing, for instance, is not conversing properly). Even quarrelling does not happen if our language does not know how to “quarrel”. The pragmatic “little machine” will therefore have to know the culturally defined situational categories that language is supposed to signify ; otherwise, we would speak out of order, use wrong turn-taking, etc. Pragmatics in this sense is really a particular semiosis, and an important one, since it is when language is used in culturally defined situations that its conceptual meaning is converted into referential meaning. |

9 Cf. E. Benveniste, Problèmes de linguistique générale, t. 1, Paris, Gallimard, 1966. |

|

Finally, the personalisation that enunciation provides, and the “situationalisation” that pragmatics provides, integrate in discourse, that is, in a discursive, rhetorical semiosis, in which an enunciative personalisation expresses pragmatic situationalisation : the roles we play as speakers and hearers theatrically determine and mean the situations we are in ; so celebratory rhetoric sounds different from political rhetoric or judiciary rhetoric, and the rhetorical “sounds” will again mean these different situations, where language will carry distinct referential meanings. Enunciation, pragmatics, and discursive, theatrical rhetoric constitute the overarching, transcendent semiosic complex by which language is “carried” into the world of its “use”.

Figure 1. The complex functions of language. We might want to follow Ferdinand de Saussure or reinterpret him and call the lower triad of semiosis, in French la langue, or the language system, as opposed to the upper triad of semiosis, la parole, or language use10. The hinge between the lower (immanent) and the upper (transcendent) part of the complex is the core utterance semiosis we also called grammar. A theory only accepting to study the lower semiosic triad would just be a grammar theory, rather than a comprehensive, linguistic, general science of language embracing both the immanent and the transcendent parts of language as a constellation of semiosic “little machines”. |

10 Cf. F. de Saussure, Cours de linguistique générale (1915), critical ed. by Tullio de Mauro, Paris, Payot, 1972. |

|

2. Pragmatics as semiosis and diegesis What is a situational context of an utterance ? Eric Landowski suggests that such a “semiotics of situations” would coincide with a complete narrative grammar, including an account of inter-actantial relations of “manipulation”, “aspectualisations”, “modalisations”, etc.11. One of the main points of Greimasian semio-narratology is, in fact, to theorise the narrated content, the story, apart from narration itself, thus as a series of situations where things simply happen to people, and the narrator has not yet arrived, so to speak (the narrator supposedly arrives through subsequent “discursivisation”). The semantic level of the narrated is separated from the semantic level of the narrating, in the same way as the signified is seen as distinct from the signifier. Thus, a situation is simply an episode in the signified diegesis of a (possible) story. The next question will then be what the little pragmatic machine, or the semiosis of situations, recognises as diegetically relevant episodes, which may thus contextualise language use. Is there really a canonical set of situational parts in a canonical sequence forming the “whole” of a story ? The claim to have found it would be strong, and no doubt far too strong, unless we believed that Propp and Greimas really solved the universal mystery of defining narrative structure12. Nevertheless, the problem of classifying situations and thereby, if possible, opening a path towards a structural pragmatics is relevant; it has to be addressed, as Landowski intimates in his 1983 lecture. Otherwise, pragmatics would let psychology and sociology define not only contexts but pragmatics altogether. Such a relinquishment would, in fact, be unfortunate because the sociological categories would be too distant from the situational format, and the psychological categories would be too proximal, too intimate, to match the format. |

11 As Landowski put it in his 1983 symposium lecture, “What is being dealt with here is the ‘semiotisation’ of context, or, rather, the setting up of a semiotics of situations” (“Pragmatics and Semiotics. Some Semiotic Conditions of Interaction”, in P. Perron and F. Collins, op. cit., p. 101). 12 Innumerable attempts have been made, including my own. Cf. “Forces and Spaces...”, in P.Aa.Brandt, Cognitive Semiotics. Signs, Mind and Meaning, London, Bloomsbury, 2020. |

|

Let us then assume that language is used in situations and that situations are diegetic. Speaker and hearer are “actants” and inscribed in a presupposed narrative and “actantial” semantics. Now let us consider an example, the expression to make sure. Cambridge Dictionary : “to act so that, or check that, something is certain or sure”. Whether by acting or by checking, to produce a state of belief. The conceptual meaning of the expression is open, so the task of the pragmatic setting of its use is to deliver its referential meaning in context. Here is a context : Two Hunters are out in the woods when one of them collapses. He doesn’t seem to be breathing and his eyes are glazed over. The diegetic unfolding inscribes the expression /make sure/ in a dialogue, again, inserted in a story. We may see this narrative context as consisting of four phases : 1) the collapse ; 2) the call ; 3) the advice containing the performative utterance let’s make sure ; 4) the killing. |

13 Italics mine. This joke was rated and declared to be preferred over a thousand other jokes by a large American test population, as reported in the science journal Nature. ScienceUpdate, October 4, 2002. |

|

The “actants” are staged as hunters, therefore armed. (1) presents a crisis. (2) makes it a catastrophe : the speaking hunter, in panic, makes a mistake by mentioning his partner as deceased. (3) displays the consequence : the operator’s epistemic advice reuses the fatal expression ; (4) thereby triggering the conclusion, the killing of the collapsed hunter — told from the operator’s viewpoint, so the act is only heard, not seen. Crisis, catastrophe, consequence, and conclusion form a diegetic series of narrative situations offering variable dynamic conditions. In this story, these first include the participants’ fragile bodily conditions (collapsing) ; then a fragile psychological condition (panic) ; a fragile linguistic sensibility and intelligence ; and the fatal mistake rendered probable by the condition of carrying arms14 : (4) refers back to (1) in this respect. |

14 This is a particularly fine joke for Americans. |

|

Maybe the experience of life is diegetic in this or a similar sense ? A recurrent contextual rhythm of four canonical phases might then underlie our apparently fluid experiential time and connect perception and reflection by the same backwards reference we find in narrative literature and jokes15. This contextual rhythm, implicit or explicit, might then form a discreet elementary micro-narrative phenomenological music of time presupposed by the larger historical contextual frames that interest hermeneutics and the disciplines of historiography, where the experiential dimension disappears, and where the linguistic problem of contextual determinations of meaning are therefore less relevant. |

15 P.Aa. Brandt, Cognitive Semiotics. Signs, Mind and Meaning, op. cit., includes a chapter explaining this diegetic model and illustrating it by the reading of short stories by Maupassant, Borges, and Hemingway. |

|

Making sure is either assertive (stating) or performative (acting). In modern standard pragmatics, the distinction between performative and assertive meaning is well-known and accepted as relevant across various terminologies. Only assertive meaning can carry truth value. Performative meaning, instead, can carry validity or “speech act force”. In modern standard semiotics, as in Landowski, supra, this pragmatic distinction is translated into semiotic terms of modality : epistemic utterance force (truth value) versus deontic utterance force (performative value), respectively. In French, this translation is particularly tempting, since the French language only has two pure modal verbs, pouvoir and devoir, the former basically epistemic, the latter basically deontic — although, of course, A.J. Greimas’s modal syntax complexifies the field in many ways. Standard semiology also essentially distinguishes two semantic sign types : icons (signs of possibility, according to C.S. Peirce) and symbols (signs of necessity, whether logical or other). Of course, such dichotomies do not in any way explain the variations in force and value. We would like to better understand how the dichotomies work, why they work, and whether they account exhaustively for the types of meaning that exist in the pragmatic world. Terminologies alone do not satisfy our curiosity. |

|

|

Symbols are signs of doing, and icons are signs of being : symbolic signs are always instructions calling for acts, physical or mental (in math, music, social codes, etc.), whereas iconic signs are manifestations of seeing something, physically or mentally, in certain ways. In language, therefore, words are symbolic, and sentences are iconic16. So, lexemic signs are “arbitrary”, conventional and, in a sense, performative, comparable to imperatives, orders in context (like social graphic signs : flags, emblems, injunctions : No smoking ! Wrong way ; No u-turn...) Words are instructions for the mind to follow. Sentences are motivated co-lexemic signs, whose connecting morphemes create a sort of assembled conceptual predicate to a scene, an image of it, a simulacrum of a representation ; only in ritual uses do sentences become symbols. |

16 This statement may seem a little blunt. What is meant is the following : Words are firstly instructions for the mind to actualise concepts, whereas sentences construe imaginable scenarios. |

|

Icons are signs of being, that is, of something being seen as something, as a subject with a predicate that invites the addressee to share the predication and, thereby, establish an affective bond with the sender. |

|

|

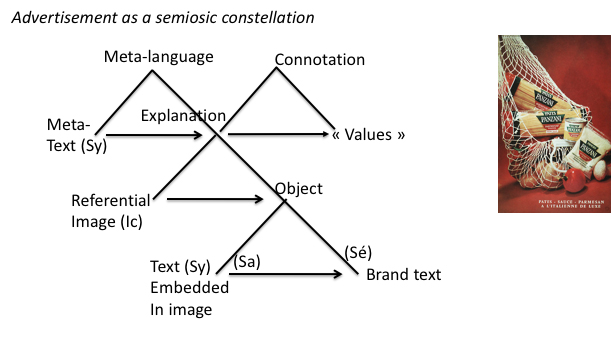

When icons and symbols combine, the operation consists in establishing the affective iconic bond and then superimpose a symbolic instruction to act accordingly, namely as the predication suggests (in caricatures : dissociate yourself from the iconic subject, reject it ; in advertisements : associate yourself with the subject, buy it). Communication in the social sphere mainly uses such icono-symbolic messages ; the combination is, so to speak, the basic formula for manipulation. Roland Barthes discusses it in his famous article “Rhétorique de l’image” on a Panzani advertisement17. Semiotically speaking, there is in this advertisement a double superposition, namely a (symbolic) text IN the image and a text ON the image. Figure 2 shows an unfolding of the result, an image that connotes, has a meta-semiotic comment, and contains a text (naming the brand announced) ; hence a complex of four semiosis.

Fig. 2. The rhetoric of image and text. In this graph, the connotative semiosis taking the iconic semiosis as its expression derives its abstract content from the metonymic meaning of the iconic content. Composition and chromatic properties of the image can trigger rich associations. Connotation and metonymy are closely related. The driving force in such semiosic constellations is always the affective effect of the iconic parts (the referential image and its metonymic connotations) and the deontic effect of the symbolic parts (the metatext and the embedded text). |

17 R. Barthes, “Rhétorique de l’image", Communications, 4, 1964. |

|

There is, however, a third type of sign, besides symbols and icons, namely diagrams18. These are neither arbitrary-and-performative nor image-like, and, similar to their representational content, they are neither about doing nor about being-and-feeling. Instead, they are graphic or gestural signs of minding — diagrams spontaneously use labelled arrows, boundary lines, bubbles and boxes, imaginary topologies of many sorts, which are schemas, models, or “theories” of how things may be connected. Diagrams are signs of minding, modelling, ideation, and surprisingly enough, the most important sign type in the social world, while also being the most ignored. There are reasons to believe that thinking in itself is diagrammatic and that the diagrammatic semiosis constitutes the semiotics of the mind itself, whether the conscious or the unconscious part. Ideas we exchange are most often neither instructions nor factual or idealised pictures ; they may instead be sketches of a program, a half-baked plan, a hypothetic construction, building blocks of a problématique, as the French say, an imaginary architecture to be completed by self or other. A diagram shows the thinking of something, simply as being thinkable (German : als denkbar). Disciplines of knowledge are mostly based on signs of this type, so the language that supports them is also of the third kind : dialogue and discourse, not just words and sentences. Dialogue and discourse allow us to “think aloud” and thereby to think together, letting others complete our thought or trying to complete others’ thoughts. When we discuss, we negotiate a shared imaginary architecture corresponding to a diagram and, sometimes explicitly, a drawn diagram on a whiteboard or paper to which we can point. Symbols, icons, and diagrams are three fundamentally different sign types in two ways. Firstly, by the constitution of their semiosis : the expression-to-content relation is conventional and non-motivated in the first case, non-conventional and motivated in the second case, and neither conventional nor motivated in the third case19. Secondly, the type of meaning they convey is different : the addressee of symbols is called upon to act in some manner (the address is deontic : “you are suggested to do X”) ; the addressee of icons is called upon to perceive something in a specific manner (the address is alethic, and therefore affective20 : “you are invited to feel this about X”) ; and diagrams invite the addressee to connect ideas, i.e. think (so the address is epistemic : “we may understand the problem X like this”). The sign types are as mutually irreducible as the meaning types21. Responses and pragmatic exchanges differ according to these variations. You may obey or contest in the first case ; be captivated or repelled in the second ; and be interested or sceptical in the third. Discourse is possible in all cases, but the dialogue is optimal in the third. Dialogue becomes quarrel if the exchange is entirely symbolic ; by contrast, it vanishes or becomes a mutual echoing if the exchange is entirely iconic. We will of course want to know why this is so. It will therefore be useful to consider the interrelations of meanings and their signs in social life and in our subjectivity. |

18 Peirce’s third semantic sign type is, of course, the index — unfortunately, a poorly elaborated type. When we perceive one event (smoke) and infer another event (fire), which is the case in all forms of perceptions, except some aesthetical forms, then the world is not signifying to us what it intends us to think, as by sending us a signifier to trigger a signified in our mind. The index is not a sign since it is not intentional. What is happening instead is that the perception contains an inference. We have to interpolate a schema between the first categorisation event (smoke) and the second (fire), either a mereological or a causal schema. These schemas are mental diagrams, and they are of the exact same constitution as our expressive diagrams. Therefore, the third sign type is the diagram, not the index. Furthermore, the index is often taken to include the phenomenon of deixis, as if the world wished to “point to” an object in order to call our attention to its meaning. Deixis is instead the enunciational aspect of all expressed signs — the frame of the picture ; the signpost of the traffic sign. Only mental diagrams do not have deixis. 19 This is not the standard explanation of the difference. “Motivation” here means orientation towards a goal known beforehand, in casu imitation of the figurative properties of the target or imaging. 20 Our feelings, whether they are the emotions of the moment, the moods of the day, or the passions of our life, react to what we see as true. You do not get angry if you do not feel certain you are being insulted — “perhaps” is not enough. Inversely, feelings can trigger beliefs, which is why manipulation, in the unethical sense, is possible. 21 Diagrams may be the evolutionary origin of symbols and icons ; gesture is often neither conventional-instructive (as greetings are) nor motivated-illustrative (as theatrical showing is), because its basic function may be inscribing the persons communicating in an imaginary space of presently shared meaning. We may find the same basic function in art, which is neither commanding nor illustrating. Roman Jakobson’s poetic function corresponds to the meaning of this basic diagramming aspect of gesture. |

|

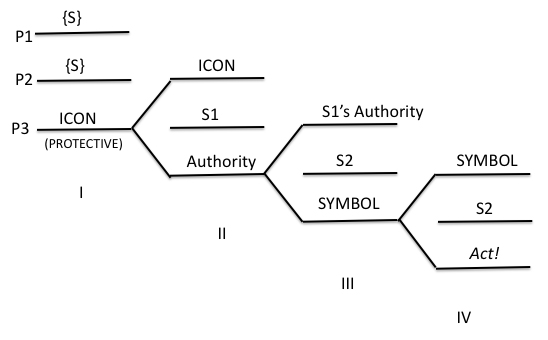

Symbolic meaning rests upon principles of authority, namely that of the instances that back up the speaker and entitles the enunciator to use performatives in specified situations. Authority, in this sense, includes named institutional identities (ministries, political parties, corporative, industrial, religious, etc. entities) and traditional cultural, historical references (memorable events, dates, personal statuses, domains of knowledge, etc.), and allows speakers and writers to express authoritative “values” instead of their own thinking. All commands, instructions, and other imperative utterances receive their “speech act force” from a presupposed entitlement signed by an authority, at least in the imaginary mode. The ritualisation of commands (uniforms, gestures, formulaic phrasing) manifests this depersonalisation of the performer. I would like to add that the ritualisation and the depersonalisation of the symbolic performer also produce another relevant effect : iconisation. The performer plays a theatrical role and becomes an image of the non-personhood of authority — of its rigidity, the scary inanimate statue we call power. Ordinary iconic meaning is not backed by any such authority. It relies only on the affective meaning of the depicted motif, which means that making an iconic representation of something is (a symptom of) affirming its affective meaning. Therefore, icons of the imaginary gestalt of authority, that is, icons of the source of symbolic force, may be the foundational semiotic function that constitutes power in general22. |

22 However, the “source of symbolic force” still has to qualify for the iconic cult that inscribes it in the logic of enunciation. I have argued elsewhere (The Music of Meaning, op. cit. ; Cognitive Semiotics, op. cit. ; “Crises et mondes. Réflexions viro-sémiotiques en août 2020”, Acta Semiotica, 1, 2021) that the origin of authorities of all kinds may be the need for and the belief in protection. (Money protects, and ethnic, religious, and other strong collective identities, even mafias and tribes, protect. Money was named after Juno Moneta, the protective goddess of Rome. Temples became banks). |

|

The mechanism described can be analysed in terms of enunciation. There is an elementary structure in which the first person (enunciator, P1) gives the third person (object of attention, P3) to the second person (enunciatee, P2). The constitution of power uses three embedded instances of this structure : I : a human collective (P1) offers a cult ICON (P3) to itself (P2) ; II : The ICON (as P1) then confers authority (A, P3) to a person S1 (P2) ; III : This person S1 (as P1) finally gives another person S2 (P2) a symbolic message, an order (SY) ; IV : the order (P1) tells S2 (P2) to act accordingly (P3).

Fig. 3. The semiotic constitution of power through enunciation23. The uncanny statue of power (the icon of authority) stands behind the instance authorising S1’s symbolic, performative acts, and it emerges as a compulsive motif of depiction : portraits of rulers hanging in the offices of their servants, monumental statues of famous and supposedly great historical persons, placed in the urban landscape, pompous architecture of banks and businesses, even advertisements linking the power of brands to images of their “greatness” ; election posters, etc. — all such semiotic displays, iconic and symbolic, and eventually the entire social iconicity, may consist in offering competing cults of implied symbolic power holders of all kinds. |

23 This enunciative cascade would also be illustrated by a Christian priest (S1) who blesses a believer (S2) in the name of God. |

|

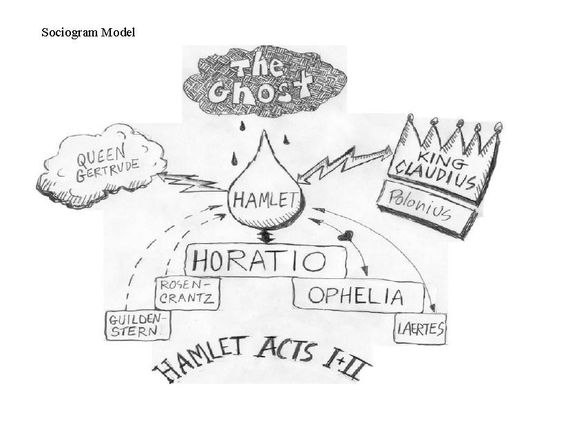

Universally, the iconic semiosis may have a symbolic semiosis hidden in its content, as in fig. 2. Thereby, affect and duty — fear and pride — will be connected in the complying social addressee’s mind. Hence the interest of Barthes’ analysis : if social power is a pragmatic effect of socio-semiotic structures, a possible counter-force may be sought in critical structural commentary. Diagrammatic meaning, as it happens, can be critical. It can oppose iconic cult and symbolic obedience. It always “occurs” to the thinking mind, which “gets” ideas instead of actively producing them. Thoughts are mental diagrams that form the elementary, “occurring” contents of consciousness, for example, as maps of one’s present location, intuitions about relations between present persons, and about the time frame of present doings (something is still the case, but something else is already the case). More abstract diagrammatic contents are supported by worded labels or other markers, imported from memory, and inserted in the nodes of the intuitive graphics.

Fig. 4. A sociogram example. A literary drama is slightly more abstract than an episodic experience, essentially because we are not in it. We are abs-tracted from it, and its understanding becomes an intellectual challenge to meet by diagramming. Science is built upon elaborate models of abstract empirical domains of the world ; it “formalises” its intuitive diagrams into models, which then underlie scientific theories. Political life would, on the other hand, be impossible without diagrams analysing the respective force of competing powers. The contemporary version of global political life has conferred overwhelming iconic-symbolic capacities to the digital media and is responsible for creating a dangerous imbalance between power and critique. Diagramming on screens is mainly seen in critical programs, which are becoming rare ; one reason is that diagrammatic thinking is slow and that digital time is an expensive commodity demanding fast action ; another reason is that global culture may be decreasingly prepared for autonomous alphanumerical, diagrammatical, mental activity by general education — except for weather or stock exchange reports. Critical activity is then bound to unfold wildly in the shape of bodily conflicts and material clashes of collective “identities”, each with its protective iconography. |

|

|

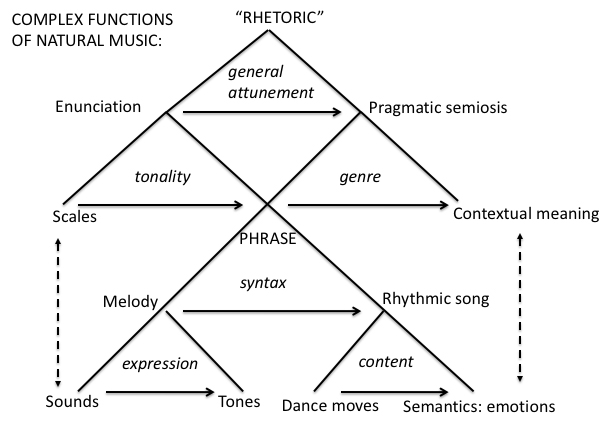

The rhythmic emission of tonal phrases is probably the earliest semiotic activity of our species. Before serving as a generalised anaesthetising tapestry for all sorts of messages in the media, it was mainly used for celebrations. Music for weddings, funerals, coronations, memorial events of all kinds was fundamental. Under certain circumstances, it had and still has the phenomenological capacity to extend the moment of celebration : to let “time stand still”. Concert music is self-celebrating and can be considered as experimental or laboratory music, as opposed to what I will call natural music, the sort that has been with us in our different cultures from their beginnings. The pragmatics of music24 is thus a global, universal, and evolutionarily primordial concern. Its generality is the same as that of language, and, curiously, music unfolds a closely similar structural complexity. |

24 See C. Small, Musicking : The Meanings of Performing and Listening, Lebanon (NH), University Press of New England, 1998. |

|

Musical semiotics has in fact, like language, an immanent and a transcendent aspect. In music, certain sounds are performed and perceived as discrete tones, which are parts of melodic lines (syntagmatic axis) and also parts of tonal scales (paradigmatic axis) based on octave recognition. This aspect is the “phonetics” of music. The melodic wholes have necessary rhythmic properties that determine how the involved bodies will move to it and especially dance, thereby expressing particular emotional states. These states are “staged”, induced by the music or called into being by its experience, and constitute the immanent semantic meaning of the specific songs played. In modern, academic music, where corporeal movements are often suppressed, the dancing and its meaning are mentalised and “performed” by the imaginary homunculi in your head, whether one is a musician or a listener. The transcendent aspect includes the situation connoted by specific musical phrases and by the tonality chosen and used ; scales are often specific for specific contexts : morning music, evening music, night music, winter music, spring music, summer music, autumn music, high-status scales, low-status scales, etc. as if the calendar and the entire social spatiotemporal world were represented in the inventory of a culture’s acknowledged tonal scales. Tonality and pragmatics are thus naturally connected. The analogy between the complex semiosis of language and those of music may make the following diagram easier to interpret.

Fig. 5. The complex semiosis of music. It is likely that the neuro-biological disposition for language is very similar to the disposition to make and enjoy music. Music may even have been laying the neural ground for language25. |

25 The strange human habit of singing utterances instead of just humming or musicking by instruments makes the connection between music and language even stronger. Syllables are then superimposed on tones and melodic phrases on grammatical phrases. Semantically, linguistic meanings and musical, emotional meaning will then cover each other and create strong impacts. Social life may have started as some sort of ongoing, non-fictive opera. |

|

In language, the integration of immanent, conceptual meaning in transcendent, pragmatic, referential meaning is an essential aspect of semantics, as we have seen. In music, this integration comes to the fore as a duality of feelings of the “character” of a given work (if written) or song (if not) and the “character” of the situation of performance : music “for” funerals (sad), weddings (happy), coronations (solemn), military parades (awe-inducing) ... — often linked to power displays. If power is rooted in collective, intersubjective iconicity (subjects seeing and believing what other subjects are seeing and believing), as suggested above, then the mere sharing of music, both seen and heard, will reinforce this constant re-founding effect of iterated collective performances that pertain to the existence of social powers, whether affirmative or contestant. |

|

|

Through it all, Welser-Möst and the [Cleveland] orchestra are dashing partners, surrounding their guest [Radu Lupu] in vibrant colors without washing out any of his. On Thursday, they also helped steady him during the Adagio [of Bela Bartok’s Piano Concerto No. 3], when a ringing cell phone twice poked holes in the silken musical fabric he was weaving. To listeners, the noise was simply rude. But to Lupu, it must have been painful, like lightning striking. Clouds occasionally gather in the E-flat trio, though Schubert is resilient enough to emerge from minor-key territory and let the sun shine in his inimitable way. Speaking about music as heard is not an easy task. Strikingly often, critics seem to refer to meteorology rather than to tonality. Above : lightning, climate, clouds, sunshine — but also vibrant colours, silken... fabric, and in all cases, visual, auditive, and often also tactile sensations (silk) that happen in an imaginary space far from the concert hall, and far from what is written in the composition being played, in the above cases. |

26 Quoted and discussed in P.Aa. Brandt, “Weather Reports : Discourse and Musical Cognition”, in K. Chapin and A.H. Clark, Speaking of Music : Addressing the Sonorous, New York, Fordham University Press, 2013. Italics mine in both quotations. |

|

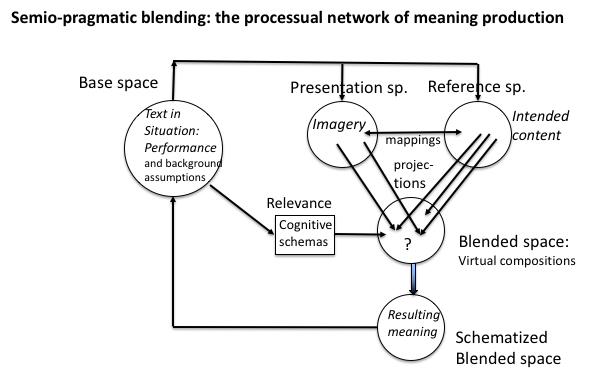

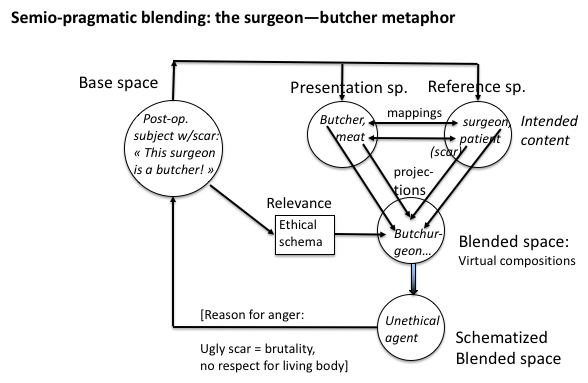

You may be thinking of metaphor to explain this phenomenon. Language is not prepared for describing sensory perceptions that activate deep registers of the soul, so we use expressions of weather observations and other highly emotional imaginary contexts to express what we feel. However, metaphor would supply imagery to a topic that could also be covered literally ; here, there is no available literal wording of what is experienced. In some books, the case is then called catachresis, or necessary metaphor (table leg, headquarter, ...). But in metaphors, the image covers, and often hides, the referent (target) and, so to speak, signifies it. In the concert hall, the sounding tonal events inversely signify the reported imagery ! This imagery seems to be the target of the tones. I have proposed to treat the phenomenon as “inverted metaphor”27. Anyway, the meaning of music is often experienced as related to this imaginary content28. There is a mental space of imagery, often cosmic or meteorological, or just narrative (as in note 16), and there is a different mental space containing the sensory perception ; they connect in interesting ways, not only by the possible mappings between items of each space but also by appearing as if they were one and the same blended space : Radu Lupu weaves silken fabric, Schubert lets the sun shine (in the quotations above). The semiotic and cognitive theory of blending, or conceptual integration, offers a pragmatically relevant theory of such experiences and textual occurrences of double-space semantic descriptions29. In this theory, there is a semiotic Base space, a situation of experience or communication, where subjects exchange signifiers, and signifieds therefore emerge in their mind according to the semiosis discussed above. These signifieds are now further observed as forming spaces around themselves instead of just appearing as isolated nominal concepts of thought. It is suggested that we think and produce meaning through processes that establish, hold, and combine mental, semantic spaces where our isolated concepts are contextualised, allowing them to change and merge, thereby giving rise to new concepts30. The most interesting aspect may be the discovery that the blending process must be stabilised by a schematisation stemming from Base space, that is, from the reality of the thinking or communicating subject(s)31. In “this surgeon is a butcher”32, the evaluative and affective meaning produced stems from the ethical schema of helping and harming applied to the blend, not from the generic butcher. Schemas of different kinds are activated by the immediate clash of mapped terms (surgeon ? butcher !) and are semantically foregrounded in the blend. Each schema may be either generally cultural or locally social, it may be rooted in history or in phenomenology, or emerge as part of the present situation, and even be imported from ongoing dialogue since the base space it comes from has variable ontological depth ; and this pragmatic anchoring is thus a necessary condition for the meaning production in the blend to happen. This metaphor model, which can be generalised to other tropes, first of all to metonymy, shows that in blending processes, pragmatics is inherent in semantic. (See figure 6 below). |

27 Cf. Speaking of Music : Addressing the Sonorous, op. cit. 28 A professional violinist, Grit Dirckinck-Holmfeld Westi, recalls her memory of hearing Carl Nielsen’s violin concerto for the first time at age 12 : “The orchestra bangs out an enormous chord, and then the violin takes over, as if it says : ‘I will take care of this !’, and it’s like hearing a bird you let out of the cage and which is now just flapping around in the room”. (G. D.-H. Westi, Information Kultur, 29 May 2020). The music is heard as describing the imaginary scenario, not the other way around. 29 The theory of conceptual blending was developed by Turner and Fauconnier, who summarised and illustrated their approach in a very entertaining book, The Way We Think. Conceptual Blending and the Mind’s Hidden Complexities, New York, Basic Books, 2002. It was further developed by Line Brandt and the author, who expanded the model semiotically and pragmatically (L. Brandt, The Communicative Mind. A Linguistic Exploration of Conceptual, Integration and Meaning Construction, Newcastle upon Tyne, Cambridge Scholars, 2013 ; L. and P.Aa. Brandt, “Making sense of a blend : A cognitive semiotic approach to metaphor”, Annual Review of Cognitive Linguistics, 3, 2005). 30 See also T. Oakley, “Conceptual Integration”, in J.O. Östman and J. Verschueren, Handbook of Pragmatics, Amsterdam, Benjamins, 2011. 31 L. and P.Aa. Brandt, “Making sense of a blend”, art. cit. 32 Example discussed in “Making sense of a blend”. |

|

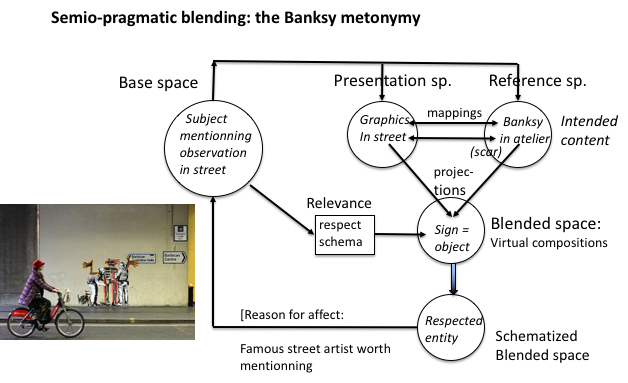

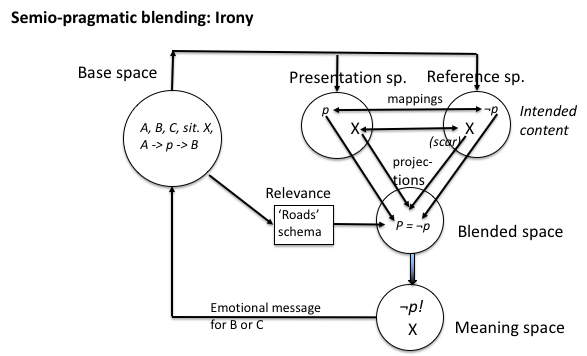

Whereas metaphor has input spaces whose contents are taken from different experiential domains33, metonymy uses input from the same domain in both mental spaces. Example : “I saw a Banksy in the street today”, meaning a graphical work by Banksy. The artist referred to is in one space, hence called Reference Space in the model, whereas the drawing is in the space of present perception, the Presentation Space. In the blend, the artist seems to materialise in the scenario as reincarnated in his artwork. Both metaphor and metonymy are counterfactual in this sense. But in the latter case, the schematisation is of a particular nature : it expresses a respectful attitude towards an authority of some kind, positive or negative. Using a part to “mean” a whole, or inversely, or a concept for a related concept, is invariably an operation schematised as an enunciative indication of attitude, in this sense. Again, this schema emerges from the speaker’s Base space, not from the semantic contents involved. In Figure 6, I will first summarise the general model of semio-pragmatic blending and then show the blending process supposed to structure our two examples of metaphor and metonymy.

Fig. 6a. The blending model.

Fig. 6b. Metaphor.

Fig. 6c. Metonymy. The field of application of this semio-pragmatic model is much larger than what can be discussed in this presentation. (The sentence you just read is an example of theoretical metonymy : what you see represents something that is not presented but which is thus represented as worthy of your attention). |

33 Experiential domains are phenomenological regions of experiences that human cognition distinguishes and conceptualises distinctly. Spaces, Domains, and Meaning (2004, op. cit.) gives a first account of the phenomenon, after Sweetser (From etymology to pragmatics, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1990), who introduced the idea of basic semantic domains in order to account for meaning differences in modality. Domain difference as such was already presupposed in conceptual metaphor theory (cf. G. Lakoff and M. Johnson, Metaphors We Live By, Chicago, The University of Chicago Press, 1980) but was never theorised or even discussed as an interesting phenomenon : why do we naturally develop domains of experience so that moving a categorial concept between domains changes its meaning ? |

|

We may, however, add the tricky case of elementary irony. Wayne Booth offers this example : A man enters his office totally soaked after having biked from home under torrential rain and greets his colleague with few words, something like “Nice weather today”34. Deirdre Wilson has the same sort of examples : Mary (after a difficult meeting) : “That went well”35. Classical accounts define irony by formulae like this one : 1) A says p to B; 2) A knows that ¬p; 3) A intends B to understand p in (1) as meaning ¬p. |

34 W. Booth, A Rhetoric of Irony, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1974. 35 D. Wilson, “The pragmatics of verbal irony : Echo or pretence?”, Lingua, 116, 2006 |

|

The lemmas (1) and (2) alone would define p as a lie. But the semantic miracle happens in (3), which therefore calls for a pragmatic explanation. What needs explaining is also why someone would think and talk like this at all. Note that in Booth’s example, it first has to rain heavily, and that in Wilson’s, the meeting has to be specified as difficult. Therefore, we need to add two more lemmas to the formula : (4) B knows that p/¬p is A’s evaluation of the situation X that p/¬p refers to, and which directly involved A36 ; and (5) : the use of p in (1) and (3) expresses A’s frustration, to be empathically shared by B, caused by a very high degree of ¬p in X. The instantiations of the last lemma (5) often manifest a semiotic dimension, a facial or gestural expression, or a phonetic aspect, a modification of intonation, as if the speaker were quoting someone. To clarify, let us now project these observations onto the blending model. In the base space, we have A, B, the situation X (heavy rain or difficult meeting) and A’s utterance ‘p’. In the Presentation Space of the network, there is the evaluation p of X, and in the Reference Space, the contrasting evaluation ¬p of X. In the blend, p and ¬p of X somehow merge, and, after an implicit schematisation, yield the content of the Meaning Space, ¬p!. |

36 Line Brandt, in The Communicative Mind. A Linguistic Exploration of Conceptual, Integration and Meaning Construction (Newcastle upon Tyne, Cambridge Scholars, 2013), discusses these and other more complex examples and pragmatically concludes on Wilson’s analysis of irony, that is, on ironic enunciation, that irony is not a propositional effect, but that it takes specific situational contexts and specific intersubjective speaker-hearer relations to achieve ironic effects. |

|

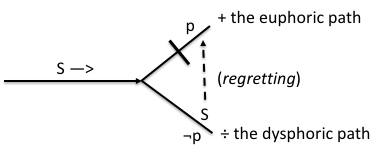

There is, in fact, a schema characteristic of irony ; we might call it “the road not taken” : S, the subject, follows a path that suddenly bifurcates in such a way that there is a very attractive path and a repulsive path, and the former is barred ; therefore, S must take the latter, while still thinking of the other one and regretting not to have been able to be on it.

Fig. 7a. The schema : “the road not taken”. Note that irony can be “biting” ; this aspect “bites” at the barrier on the p branch : something went wrong, and the cause is evident, namely that “you blew it !”37. In this case, the addressee is foregrounded as responsible for the barrier. Enunciation is active in this way, particularly in dialogues of quarrelling. |

37 For example : A and B are quarrelling. B, A’s wife, underlines her point of view by throwing the kitchen’s crockery against the walls and on the floor, creating an impressive mess. A : “Nice work, my dear !”. |

|

The network activates the schema in the Relevance input to the blend, where p and ¬p merge, paradoxically, absurdly, but again are disambiguated by the schema and “resolved” as an emphatic ¬p! to be shared in the pragmatic Base space by A and B or else by A and bystanders (C), as in polemical irony, where A and B are antagonists.

Fig. 7b. Irony. The blending mechanism is ubiquitous in language and graphic imagination, such as cartoons, caricature drawings, advertisements, and poetry. In all contexts where the expression itself is foregrounded, which is the case whenever emotion prevails, our communicative thinking tends to split the semantic content into two mental spaces interrelated as a Presentation to a Reference, and, fundamentally, as a foregrounded predicate to a known subject, in the logical, propositional sense. |

|

|

In poetry, where the stipulated situational context (X) is aesthetic (that is, determined as both sacred and intimate38), irony is a possible “strategy”, besides all sorts of tropes and linguistic and graphic operations on the form of the utterance. The primary such operation is, of course, the introduction of the phenomenon called verse, whether metrical or “free”, as an expressive gesture of disruption that may be compared to the implicit negation (¬) in irony. In poetry, a referential content r is intended behind a presentation where r is disrupted by verse, tropes, figures, graphic gestures, syntactic cut-ups, and a more or less chanting vocal performance : (¬)r. We often oppose the ironic coolness and the pathetic heat in lyric contexts (poetry and songs) ; the poetic heat may stem from the fact that the disruption (¬)r appears in the Presentation space, whereas it appears in the Reference space of irony39. The fundamental poetic schema may however be almost the same. The barrier blocks the enunciator from going “directly” to the core of a content, which is sacred and intimate ; the blocking is a call for circumlocution in a very wide sense. |

38 See the analysis of semantic domains in P.Aa. Brandt Spaces, Domains, and Meaning, op. cit., The Music of Meaning, op. cit., and Cognitive Semiotics, op. cit. 39 Poetry as such may therefore be seen as a sort of inverse irony in this sense. |

|

As we have seen, meaning is determined by both immanent and transcendent semiotic structuring : it is both conceptual and contextual. The recursion of semiosis makes it possible to understand and theorise this open but non-chaotic relation between minimal, medial, and maximal sign structures and the experiential lifeworld that infuses social systems with meaning and lets cultural, semiosic, and mental content develop as a continuity. Semiotics and pragmatics are interconnected, and their bonds are indissoluble ; if cut off, pragmatics would become a part of psychology and semiotics a specialty of linguistics. The cognitive theory of mental spaces and conceptual blending needed a semiotic and, as we suggested above, a semio-pragmatic grounding in order to grow out of its initial format as a philosophical daydream. The model explained here shows how situational and experiential contributions, namely the schemas that blending processes activate, intervene in the sense-making, also called the meaning production, of the processes of creative thinking and signifying that semiotics studies ; the pragmatic interest in signifying behaviour, on the other hand, would disappear into sociology and anthropology, or collapse into linguistics, if the semiotic insistence on iconicity, symbolicity, diagrams, enunciation, and deixis did not call it back to the fundamental life of signs in human life. |

|

References Barthes, Roland, “Rhétorique de l’image”, Communications, 4, 1964. — L’Aventure sémiologique, Paris, Seuil, 1985. Benveniste, Emile, Problèmes de linguistique générale, t. 1, Paris, Gallimard, 1966. Booth, Wayne, A Rhetoric of Irony, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1974. Brandt, Line, The Communicative Mind. A Linguistic Exploration of Conceptual, Integration and Meaning Construction, Newcastle upon Tyne, Cambridge Scholars, 2013. — and Per Aage Brandt, “Making sense of a blend : A cognitive semiotic approach to metaphor”, Annual Review of Cognitive Linguistics, 3, 2005. Brandt, Per Aage, Spaces, Domains, and Meaning, Berne, Peter Lang (European Semiotics, 4), 2004. — “Weather Reports : Discourse and Musical Cognition”, in K. Chapin and A.H. Clark, Speaking of Music : Addressing the Sonorous, New York, Fordham University Press, 2013. — The Music of Meaning. Essays in Cognitive Semiotics, Newcastle upon Tyne, Cambridge Scholars, 2019. — Cognitive Semiotics. Signs, Mind and Meaning, London, Bloomsbury, 2020. — “Crises et mondes. Réflexions viro-sémiotiques en août 2020”, Acta Semiotica, 1, 2021. Fauconnier, Gilles and Mark Turner, The Way We Think. Conceptual Blending and the Mind’s Hidden Complexities, New York, Basic Books, 2002. Fraser, Bruce and Ken Turner (eds.), Language in Life, and a Life in Language : Jacob Mey. A Festschrift, Bingley (UK), Emerald, 2009. Greimas, Algirdas J., “Pragmatics and Semiotics. Epistemological Observations”, in P. Perron and F. Collins (eds.), Paris School Semiotics. I. Theory, Amsterdam, Benjamins, 1989. Hénault, Anne (ed.), Le sens, le sensible, le réel. Essais de sémiotique appliquée, Paris, Sorbonne University Press, 2019. Hjelmslev, Louis, Prolegomena to a Theory of Language, Baltimore, Indiana University Publications, 1943. Lakoff, George and Mark Johnson, Metaphors We Live By, Chicago, The University of Chicago Press, 1980. Landowski, Eric, “Pragmatics and Semiotics. Some Semiotic Conditions of Interaction”, in P. Perron and F. Collins (eds.), Paris School Semiotics. I. Theory, Amsterdam, Benjamins, 1989. Oakley, Todd, “Conceptual Integration”, in J.O. Östman and J. Verschueren, Handbook of Pragmatics, Amsterdam, Benjamins, 2011. Perron, Paul and Frank Collins (eds.), Paris School Semiotics, I. Theory, Amsterdam, Benjamins,1989. Saussure, Ferdinand de, Cours de linguistique générale (critical ed. by Tullio de Mauro), Paris, Payot, 1972. Small, Christopher, Musicking : The Meanings of Performing and Listening, Lebanon (NH), University Press of New England, 1998. Sweetser, Eve, From etymology to pragmatics, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1990. Wilson, Deirdre, “The pragmatics of verbal irony : Echo or pretence?”, Lingua, 116, 2006. |

|

1 A.J. Greimas, “Pragmatics and Semiotics. Epistemological Observations”, in P. Perron and Collins, Paris School Semiotics, Amsterdam, Benjamins, 1989, p. 93. This was read as an introductory lecture to the International Symposium on Pragmatics and Semiotics held at the University of Perpignan the 17-19th November 1983. 2 An example : The concept of justice means different things in the (transcendent) context of revenge or retribution and in that of jurisdiction. In itself, immanently, it contains a schema of balance or equilibrium between “weights” of penalty and wrongdoing. 3 Meaning is expressed in many ways, and language is only one of them, although presumably predominant. The realm of available expressive activities in the human world is extensive. For example, there are certainly reasons for developing a pragmatics of music, as of the vast family of iconic media and symbolic gestures and objects (think of architecture). Nevertheless, it may be wise to start out by considering language in particular ; very few of the other forms would have evolved without it. 4 The function that ties a content to an expression, or a signified to a signifier, is an automatic mental mechanism, not a process of reasoning like the interpretation of a treatise of philosophy ; I use the diagrammatic format of a triangle for a semiosis so that the “coding” mechanism can occupy an angle. This “little machine” is a cognitive routine intimately related to the neural processes that make us think. We do not know yet what they are and how they causally work, but we can approach them by observing as closely as possible what they are achieving : the different forms of meaning-making that pervade the human world. 5 Cf . L. Hjelmslev, Prolegomena to a Theory of Language, Baltimore, Indiana University Publications, 1943. R. Barthes, L’Aventure sémiologique, Paris, Seuil, 1985. 6 The principle of semiosic recursion is presented in P.Aa. Bandt, “The Sign Cascade. A Basic Format of Semiotic Apperception”, in B. Fraser and K. Turner (eds.), Language in Life, and a Life in Language : Jacob Mey. A Festschrift, Bingley (UK), Emerald, 2009. A broader unfolding of this glossematic discovery may be found in P.Aa. Bandt, “From Linguistics to Semiotics : Hjelmslev's fortunate Error”, in A. Hénault (ed.), Le sens, le sensible, le réel. Essais de sémiotique appliquée, Paris, Sorbonne University Press, 2019, has. 7 Hjelmslev called this constellation a relation between a metalanguage and its object-language. The “meta-semiosis” that has an “object semiosis” in its content is rather the context of the embedded semiosis. This constellation is therefore of great interest to pragmatics as a study of contexts. 8 The model is explained in the chapter “The Role of Semio-Syntax”, in P.Aa. Brandt, The Music of Meaning. Essays in Cognitive Semiotics, Newcastle upon Tyne, Cambridge Scholars, 2019. 9 Cf. E. Benveniste, Problèmes de linguistique générale, t. 1, Paris, Gallimard, 1966. 10 Cf. F. de Saussure, Cours de linguistique générale (1915), critical ed. by Tullio de Mauro, Paris, Payot, 1972. 11 As Landowski put it in his 1983 symposium lecture, “What is being dealt with here is the ‘semiotisation’ of context, or, rather, the setting up of a semiotics of situations” (“Pragmatics and Semiotics. Some Semiotic Conditions of Interaction”, in P. Perron and F. Collins, op. cit., p. 101). 12 Innumerable attempts have been made, including my own. Cf. “Forces and Spaces...”, in P.Aa.Brandt, Cognitive Semiotics. Signs, Mind and Meaning, London, Bloomsbury, 2020. 13 Italics mine. This joke was rated and declared to be preferred over a thousand other jokes by a large American test population, as reported in the science journal Nature. ScienceUpdate, October 4, 2002. 14 This is a particularly fine joke for Americans. 15 P.Aa. Brandt, Cognitive Semiotics. Signs, Mind and Meaning, op. cit., includes a chapter explaining this diegetic model and illustrating it by the reading of short stories by Maupassant, Borges, and Hemingway. 16 This statement may seem a little blunt. What is meant is the following : Words are firstly instructions for the mind to actualise concepts, whereas sentences construe imaginable scenarios. 17 R. Barthes, “Rhétorique de l’image", Communications, 4, 1964. 18 Peirce’s third semantic sign type is, of course, the index — unfortunately, a poorly elaborated type. When we perceive one event (smoke) and infer another event (fire), which is the case in all forms of perceptions, except some aesthetical forms, then the world is not signifying to us what it intends us to think, as by sending us a signifier to trigger a signified in our mind. The index is not a sign since it is not intentional. What is happening instead is that the perception contains an inference. We have to interpolate a schema between the first categorisation event (smoke) and the second (fire), either a mereological or a causal schema. These schemas are mental diagrams, and they are of the exact same constitution as our expressive diagrams. Therefore, the third sign type is the diagram, not the index. Furthermore, the index is often taken to include the phenomenon of deixis, as if the world wished to “point to” an object in order to call our attention to its meaning. Deixis is instead the enunciational aspect of all expressed signs — the frame of the picture ; the signpost of the traffic sign. Only mental diagrams do not have deixis. 19 This is not the standard explanation of the difference. “Motivation” here means orientation towards a goal known beforehand, in casu imitation of the figurative properties of the target or imaging. 20 Our feelings, whether they are the emotions of the moment, the moods of the day, or the passions of our life, react to what we see as true. You do not get angry if you do not feel certain you are being insulted — “perhaps” is not enough. Inversely, feelings can trigger beliefs, which is why manipulation, in the unethical sense, is possible. 21 Diagrams may be the evolutionary origin of symbols and icons ; gesture is often neither conventional-instructive (as greetings are) nor motivated-illustrative (as theatrical showing is), because its basic function may be inscribing the persons communicating in an imaginary space of presently shared meaning. We may find the same basic function in art, which is neither commanding nor illustrating. Roman Jakobson’s poetic function corresponds to the meaning of this basic diagramming aspect of gesture. 22 However, the “source of symbolic force” still has to qualify for the iconic cult that inscribes it in the logic of enunciation. I have argued elsewhere (The Music of Meaning, op. cit. ; Cognitive Semiotics, op. cit. ; “Crises et mondes. Réflexions viro-sémiotiques en août 2020”, Acta Semiotica, 1, 2021) that the origin of authorities of all kinds may be the need for and the belief in protection. (Money protects, and ethnic, religious, and other strong collective identities, even mafias and tribes, protect. Money was named after Juno Moneta, the protective goddess of Rome. Temples became banks). 23 This enunciative cascade would also be illustrated by a Christian priest (S1) who blesses a believer (S2) in the name of God. 24 See C. Small, Musicking : The Meanings of Performing and Listening, Lebanon (NH), University Press of New England, 1998. 25 The strange human habit of singing utterances instead of just humming or musicking by instruments makes the connection between music and language even stronger. Syllables are then superimposed on tones and melodic phrases on grammatical phrases. Semantically, linguistic meanings and musical, emotional meaning will then cover each other and create strong impacts. Social life may have started as some sort of ongoing, non-fictive opera. 26 Quoted and discussed in P.Aa. Brandt, “Weather Reports : Discourse and Musical Cognition”, in K. Chapin and A.H. Clark, Speaking of Music : Addressing the Sonorous, New York, Fordham University Press, 2013. Italics mine in both quotations. 27 Cf. Speaking of Music : Addressing the Sonorous, op. cit. 28 A professional violinist, Grit Dirckinck-Holmfeld Westi, recalls her memory of hearing Carl Nielsen’s violin concerto for the first time at age 12 : “The orchestra bangs out an enormous chord, and then the violin takes over, as if it says : ‘I will take care of this !’, and it’s like hearing a bird you let out of the cage and which is now just flapping around in the room”. (G. D.-H. Westi, Information Kultur, 29 May 2020). The music is heard as describing the imaginary scenario, not the other way around. 29 The theory of conceptual blending was developed by Turner and Fauconnier, who summarised and illustrated their approach in a very entertaining book, The Way We Think. Conceptual Blending and the Mind’s Hidden Complexities, New York, Basic Books, 2002. It was further developed by Line Brandt and the author, who expanded the model semiotically and pragmatically (L. Brandt, The Communicative Mind. A Linguistic Exploration of Conceptual, Integration and Meaning Construction, Newcastle upon Tyne, Cambridge Scholars, 2013 ; L. and P.Aa. Brandt, “Making sense of a blend : A cognitive semiotic approach to metaphor”, Annual Review of Cognitive Linguistics, 3, 2005). 30 See also T. Oakley, “Conceptual Integration”, in J.O. Östman and J. Verschueren, Handbook of Pragmatics, Amsterdam, Benjamins, 2011. 31 L. and P.Aa. Brandt, “Making sense of a blend”, art. cit. 32 Example discussed in “Making sense of a blend”. 33 Experiential domains are phenomenological regions of experiences that human cognition distinguishes and conceptualises distinctly. Spaces, Domains, and Meaning (2004, op. cit.) gives a first account of the phenomenon, after Sweetser (From etymology to pragmatics, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1990), who introduced the idea of basic semantic domains in order to account for meaning differences in modality. Domain difference as such was already presupposed in conceptual metaphor theory (cf. G. Lakoff and M. Johnson, Metaphors We Live By, Chicago, The University of Chicago Press, 1980) but was never theorised or even discussed as an interesting phenomenon : why do we naturally develop domains of experience so that moving a categorial concept between domains changes its meaning ? 34 W. Booth, A Rhetoric of Irony, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1974. 35 D. Wilson, “The pragmatics of verbal irony : Echo or pretence?”, Lingua, 116, 2006. 36 Line Brandt, in The Communicative Mind. A Linguistic Exploration of Conceptual, Integration and Meaning Construction (Newcastle upon Tyne, Cambridge Scholars, 2013), discusses these and other more complex examples and pragmatically concludes on Wilson’s analysis of irony, that is, on ironic enunciation, that irony is not a propositional effect, but that it takes specific situational contexts and specific intersubjective speaker-hearer relations to achieve ironic effects. 37 For example : A and B are quarrelling. B, A’s wife, underlines her point of view by throwing the kitchen’s crockery against the walls and on the floor, creating an impressive mess. A : “Nice work, my dear !”. 38 See the analysis of semantic domains in P.Aa. Brandt Spaces, Domains, and Meaning, op. cit., The Music of Meaning, op. cit., and Cognitive Semiotics, op. cit. 39 Poetry as such may therefore be seen as a sort of inverse irony in this sense. |

|

______________ Mots clefs : blending, diagram, irony, music (semiotics of —), pragmatics, situation, tropes. Auteurs cités : Roland Barthes, Emile Benveniste, Line Brandt, Gilles Fauconnier, Algirdas J. Greimas, Louis Hjelmslev, Eric Landowski, Christopher Small, Eve Sweetser, Deirdre Wilson. Plan : 1. Modelling the relation between pragmatics and semiotics |

|

Pour citer ce document, choisir le format de citation : APA / ABNT / Vancouver |

|

Recebido em 22/06/2020. / Aceito em 04/03/2021. |