Derniers numéros

I | N° 1 | 2021

I | N° 2 | 2021

II | N° 3 | 2022

II | Nº 4 | 2022

III | Nº 5 | 2023

III | Nº 6 | 2023

IV | Nº 7 | 2024

IV | Nº 8 | 2024

V | Nº 9 | 2025

> Tous les numéros

Raconter la pandémie

|

Apocalyptic features Francesco Galofaro Publicado em 4 de março de 2021

|

|

This article is dedicated to the presence of apocalyptic themes and functions in European political discourse at the time of coronavirus. We shall mention two opposite examples : a radical leftist position, expressed by the Italian post-Marxist philosopher Franco Berardi, and a moderate conservative discourse by the President of the European Commission Ursula van der Leyen. Political language lacks categories to frame such a rare and catastrophic event. But politicians, intellectuals, and religious leaders have the duty to provide a meaning to the pandemic in order to propose actions referring to possible future scenarios. In order to do so, they retrieve interpretations from their cultural tradition. Unexpected as it may be, both the public figures we shall later quote, the leftist and the centrist, refer to one and the same source, namely the Book of Revelation, also known as the Apocalypse of John1. This classic of western religious literature addresses a theodicy problem. It refers to the early persecutions against Christians, trying to explain why God allows them, despite the worshippers’ loyalty. However, if on the one hand the Apocalypse describes terrible catastrophes and violence, on the other hand it shows the foundation of a new world, giving hope to the Christians. |

* This article is part of the research project NeMoSanctI (New Models of Sanctity in Italy (1960s-2000s) A Semiotic Analysis of Norms, Causes of Saints, Hagiography, and Narratives), which has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 757314). 1 Regarding translation, critical apparatus and the reconstruction of the historical background, we base on La Bible de Jérusalem, Paris, Cerf, 1998 (3rd ed.). |

|

The theoretical interest of the analysis lays in the relation between the borrowing of overcoded forms of the content2 and the attempt to cope with a socio-semiotic context featured by a lack of meaning or significance : basing on a semiotic approach to interaction, we shall see how the Apocalypse allows politicians to interpret the pandemic as an opportunity for a moral change. In particular, in the discourses composing our corpus, the search for a form of adjustment between humans and the virus is identified with the Second Advent : from the ruins of the old world a new one will be constructed. In this context, the rediscovery of the apocalyptic discourse assumes the functions of both providing a meaning and controlling risk. |

2 U. Eco, A Theory of Semiotics, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1976. |

|

As we shall see, Eric Landowski’s interactional model provides clues in this domain3. It helps to interpret these borrowings from the religious discourse as the attempt to cope with an “accident” involving two subjects, contemporary society on one side, and, on the other side, an abstract ethical instance whose supposed existence is called for by the empirical existence of the virus : the conflict with this instance is interpreted as the cause of the pandemic. This also suggests a connection between Landowski’s regimes and the analysis of the explosion proposed by Juri Lotman4. Political apocalyptic discourse, whose goal will be our principal research question, appears as the attempt to react to the accident by performing a manipulation of the public opinion. Apocalyptic features may appear in all political discourses, from far-right to green radical movements5. For example, according to the latter, the pandemic is a sort of punishment for Western lifestyle. A critical review of scientific papers published by the Italian ONG Legambiente reports many different hypotheses, according to which the contagion spreads with pollution : With regard to studies on the spread of viruses in the population, there is solid scientific literature that correlates the incidence of cases of viral infection with concentrations of atmospheric particles. On the contrary, the quarantine would favour a healthier air. Likely, the containment measures of the virus, above all the decrease in the circulation of private cars and traffic, have further helped to decrease the concentration levels of fine particles in the air6. |

3 Cf. Les interactions risquées, Limoges, Pulim, 2005. Landowski’s model inter-defines four regimes of interaction, meaning, and risk : programming, manipulation, adjustment, and accident (see Appendix, fig. 1). It also defines the syntagmatic relations linking these regimes, thereby allowing to outline various trajectories of transformation. On this dynamic aspect, see for example J.-P. Petitimbert, “Anthropocenic Park : ‘humans and non-humans’ in socio-semiotic interaction”, Actes Sémiotiques, 120, 2017. 4 J. Lotman, Culture and Explosion, Berlin, New York, De Gruyter, 2009. 5 On the wide presence of apocalyptic discourses in contemporary media cf. V. Idone Cassone, B. Surace, M. Thibault (eds.), I discorsi della fine. Catastrofi, disastri, apocalissi, Roma, Aracne, 2018. |

In the considered text, “Nature” substitutes “God” in the role of the sender of the pandemic, interpreted as a negative sanction. Unfortunately, while Christian god is infinitely good and forgiving, “Nature” is not. There are three reasons why the Book of Revelation is a good source of borrowings to political discourse : thematic, symbolic, and structural ones. Firstly, a thematic motive. The Apocalypse presents different topics which can be related to the present situation. For example, the prophetic vision stages an ecological catastrophe : Then the first angel sounded his trumpet, and hail and fire mixed with blood were flung to the earth. A third of the earth was burned up, along with a third of the trees and all the green grass. Then the second angel sounded his trumpet, and something like a great mountain burning with fire was thrown into the sea. A third of the sea turned to blood, a third of the living creatures in the sea died, and a third of the ships were destroyed. Then the third angel sounded his trumpet, and a great star burning like a torch fell from heaven and landed on a third of the rivers and on the springs of water. The name of the star is Wormwood. A third of the waters turned bitter like wormwood oil, and many people died from the bitter waters. (Revelation 8, 7-11). Furthermore, the apocalypse connects pandemic, economic crisis and war : And when the Lamb opened the fourth seal, I heard the voice of the fourth living creature say, “Come !” Then I looked and saw a pale horse. Its rider’s name was Death, and Hades followed close behind. And they were given authority over a fourth of the earth, to kill by sword, by famine, by plague, and by the beasts of the earth. (Revelation 6, 7-8). Second: the figurative apparatus of the Apocalypse invites the interpreter to activate a symbolic reading superimposed to it, because of its density and persistence : The textual implicature signaling the appearance of the symbolic mode depends on the presentation of a sentence , of a word , of an object, of an action that, according to the precoded narrative or discursive frames, to the acknowledged rhetorical rules, to the most common linguistic usage, should not have the relevance it acquires within that context.7 |

7 U. Eco, Semiotics and the Philosophy of language, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1986, p. 158. |

But holy scriptures are featured by a peculiar figurative rationality8. Figures in the Apocalypse represent pluri-isotopic connectors, related to a number of themes and possible readings. For this reason, the problem of the Church has always been to tame and reduce the symbolic meaning of the Books. The mystic is the “detonator” of the symbol, but immediately afterward a public “elaborator”, who establishes certain collective and understandable meanings of the original expression, is needed.9 A third reason why political discourse borrows an apocalyptic point of view on the present reality to provide it with a meaning can be found in the composite structure of the Book of Revelation, which blends two different discursive configurations10 : Epistle (Revelation 1-3) and Prophecy (Revelation 4 - 22) as we shall see later. The Epistle has an almost explicit political character : |

8 L. Panier, « Des figures dans les récits : La guérison de la femme courbée in Lc 13, 10-17 », in Camille Focant and André Wénin (eds.), Analyse narrative et bible, Leuven, Leuven University Press, 2005, pp. 425-430. 9 U. Eco, Semiotics and the Philosophy of language, op. cit., p. 146. 10 Discursive configurations are “micro-narratives with an autonomous syntactic/semantic structure, which can be integrated in larger discursive units and acquire thereby functional significations corresponding to their positions in these larger units”. A.J. Greimas and J. Courtés, Semiotics And Language : An Analytical Dictionary, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1982, p. 49. |

|

To the angel of the church in Ephesus write (...) I know your deeds, your labour, and your perseverance. I know that you cannot tolerate those who are evil, and you have tested and exposed as liars those who falsely claim to be apostles. Without growing weary, you have persevered and endured many things for the sake of My name. But I have this against you : You have abandoned your first love. Therefore, keep in mind how far you have fallen. Repent and perform the deeds you did at first. But if you do not repent, I will come to you and remove your lampstand from its place. But you have this to your credit: You hate the works of the Nicolaitans, which I also hate. (Revelation, 2, 1-6) As the speeches that political leaders address to their community (activists, voters), the sender commits his charisma to settle disputes, to warn against flawed ways of thinking, and to appeal to unity. In the terms proposed by Guido Ferraro, the structure of apocalyptic literature can be considered a beta-class architecture, whose function is cosmological11. But in the Apocalypse we also find the values of the other two architectures considered by Ferraro , i.e. alpha and gamma-classes. The Alpha-class architecture is the trajectory of realisation of the subject analysed in detail by Greimas, as the core of his narrative syntax. In the Book of Revelation, the subject’s loyalty during troubled times will be rewarded, in the end. The gamma-class architecture operates a passage from secret to truth, from not appearing to appearing12. In the proper sense, gamma-class architectures are immanent to crime fiction. These narrations do not focus on action, as would Greimas’s canonic trajectory, but on knowledge (who did what has been done ? and how ?). Perhaps this si-mile between the Book of Revelation and detective stories is far-fetched, but the composite character of the structure of the Book of Revelation presents some analogies, starting from the key-role of the narrator-witness. |

11 G. Ferraro, Semiotica 3.0 : 50 idee chiave per un rilancio della scienza della significazione, Roma, Aracne, 2019, pp. 93-138. See also, in the present volume, G. Ferraro, “L’accidente e il sistema. Forme di narrazione dell’epidemia”. 12 In his contribution to the present issue, Paolo Demuru recognises two isotopies connected to the apocalypse : the prophetic announcement of pain and the salvific value. According to our analysis, there is a third value : the revelation of the truth. |

|

2. Prophecy in two opposite political discourses In secular society, axiology and narrative architectures typical of archaic religious discourse re-emerge. An interesting example is provided by Marxist discourse. The relation between economic crisis and war appears in Lenin’s analysis of imperialism13. While Marxist philosophers tried to address this pro-blem from a materialistic point of view, the isomorphism with the apocalypse nevertheless allowed an eschatological element to enter Marxist propaganda. See, for example, the Marxian alternative “either socialism or barbarism”. |

13 Cf. V.I. Lenin, Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism, London, Penguin Classics, 2010. |

|

A manifest example of apocalyptic categories incorporated by post-Marxist political discourse is provided by the Italian philosopher Franco Berardi: Everything has stopped forever, I don’t know if you’ve noticed. Economists, professional illusionists, talk about a fall of 10%. (...) I think the collapse is much deeper and much longer than you dare to think. This is by no means to say that the pandemic caused the collapse of the global economy: it only revealed it. We were continuing to believe in the possibilities of growth, expansion and so on, but it was over thirty years ago, neoliberalism replaced impossible growth with extraction and destruction. We were running on emptiness, and the pandemic simply revealed to us that there is no path under our feet but the abyss. [Our translation].14 |

14 Interview published by the online magazine fanpage.it : https://www.fanpage.it/cultura/il-diario-del-lockdown- |

In the above paragraph, pandemic has the function to unveil the truth about capitalism. Furthermore, the virus is a punishment, and we must atone for our sin. In Berardi’s interview, the sin is thematized as a “missed” rebellion : “In the absence of a revolutionary break that changes the mode of production and the distribution of resources, the profit of some is much more important than the life of all”. Another element echoing the Apocalypse is represented by figurative rationality, a concatenation of figures which leads to a transformation : I am speaking of the civil war that is brewing between the apparatus of the American federal state and the armed supremacist militias. I am talking about the internal breakdown in the army and the opposition between the FBI and armed Trumpist militias. I’m talking about the secession of states like California and New York from a state in full disintegration. I am talking about an army of tens of millions of unemployed who like crazy grasshoppers will strike American society. In five years, the United States of America, as a federal state, as an entity unitary, will no longer exist. The “disintegration” of the United States will avenge Berardi, loyal worshipper and prophet : “I will no longer be alive to rejoice, but you who will be, remember my prediction that day, and then please make a toast to my memory”. Berardi’s perspective seems tragic, but a new covenant or a second advent can be found in his conclusive appeal to young people : Human heritage can only be saved by the autonomy of a thousand intelligent communities, technologically hyper-gifted, emotionally affectionate, and capable of defending themselves by any means necessary. The presence — or absence — of an eschatology is crucial, allowing us to distinguish between those political discourses whose only goal is manipulation from other political discourses, in which manipulation is but a first move, opening the way for a further step (either programming or adjustment). On a similar line, it is possible to draw a distinction between tragic and optimist post-Christian philosophies. While an eschatological perspective is absent in Nietzsche and Sartre, its presence in Marxist thought gives a meaning to the present struggles and more broadly to human destiny as a whole15. |

15 Cf. G. Girardi, Marxismo e cristianesimo, Assisi, Cittadella, 1976, pp. 36-37. |

|

A second example of apocalyptic political discourse is provided by Ursula von der Leyen’s speech at the European Parliament Plenary on the presentation of the programme of activities of the German Presidency of the Council of the EU (July 8th, 2020)16. The goal of the Commission was to get legitimacy in order to play a role of sender, organising the answer of the individual European nations to the pandemic through moral suasion. In this framework, according to von der Leyen’s speech, the sins people must atone are represented by individualism and short-sightedness : “Admittedly, to begin with, many were looking inwards, at the small things, and not enough at the bigger picture and from all angles”. The catastrophic situation is described with even worse figures than in Berardi’s interview : |

16 https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/ |

|

And in the last six months, more than 100,000 lives have been lost in Europe because of Covid-19. We have entered the worst recession since almost 100 years. The Summer Forecast from yesterday shows a contraction of more than 8% this year with only a partial rebound next year. This crisis is deeper and it is way broader than the one ten years ago. This sacrifice acquires a meaning in an eschatological perspective. The virus is interpreted as an opportunity to change : The Corona crisis has made us think in new and different ways about the values of solidarity and community. We are thinking in new and different ways about the great value which a united Europe brings, which must be recreated every day. (...) We pulled ourselves together and started to see things afresh through European eyes, and to feel things with a European heart. The second advent, the new covenant, is then represented by the long-term program of the European Union, Next Generation EU : And if we want to come out stronger from this crisis, we must all change for the better. There is not a single Member State that is exempted from that. We must all change to the better. And this is also what European people expect from us. They are certainly very different in their individual expectations. But they are completely united in wanting to drink clean water, to breathe fresh air, to see their children grow up in nature. And what they certainly do not want is that politics contributes to increase flooding, heat waves, droughts and the loss of millions of species — and this is a very real scenario in case of non-action. And therefore, economic recovery is inseparable from the European Green Deal, as well as digitalisation and resilience. Thus, New Europe will be green and digital. Other long-term goals listed by the President are Research, Innovation, Migration, Foreign Policy, Security. In short : the best possible world17. |

17 About “the pillars of the New Europe”, cf. https://ec.europa.eu/info/live-work-travel-eu/health/coronavirus- |

|

3. The pandemic between accident and explosion As already suggested by Paolo Demuru, a theoretical synthesis connecting Landowski’s regime of the accident and Lotman’s notion of explosion would be advisable, in view of a comprehensive model of cultural change : Both Landowski’s accident and Lotman’s explosion designate a break in the gradual evolution of the history of individual and/or collective subjects (cultural community, social groups and organisations, political institutions, nation-states) that leads to a phase of semantic indeterminacy whose resolution will later be the object of dispute between competing intentionalities.18 From this point of view, the pandemic may be considered as a particular case of explosion: At the moment of explosion, eschatological ideas, such as the affirmation of the proximity of Doomsday, of world revolution, regardless of whether it begins in Paris or St Petersburg, and other analogous historical facts are significant not for the fact that they generate the “last and decisive battle” beyond which must come the reign of God on earth but rather for the fact that they induce an unprecedented tension in popular forces and introduce dynamic elements to the apparently static layers of history. Humanity characteristically evaluates these moments in categories which are either positive or negative.19 |

18 P. Demuru, “Between Accidents and Explosions : Indeterminacy and Aesthesia in the Becoming of History”, Bakhtiniana 15, 1, 2020, p. 85. 19 J. Lotman, Culture and Explosion, op. cit., pp. 17-18. |

However, a comparison between European and Russian examples of political, cultural, and semantic discontinuity allows Lotman to distinguish between a ternary (i.e. mediated) and a binary model of cultural change. As Lotman pointed out, In ternary systems, ex-plosive processes rarely penetrate all layers of culture. As a rule, what occurs in this instance is the simultaneous combination of explosion in some cultural spheres and gradual development in others.20 Lotman is not re-proposing the timeworn opposition between reform and revolution ; he is rather comparing different types of revolutions : “When passions were high in the National Assembly and the theatre, in the streets of Paris close to the Palais royal life was merry and far removed from political life”21. On the contrary, in Russian culture, “At the level of self-description we encounter the idea of the complete and unconditional destruction of existing developments and the apocalyptic generation of the new”22. |

20 Ibid, p. 172. 21 Ibid, p. 173. 22 Ibid. |

|

If this analysis is correct, we can ask whether the pandemic political crisis represents a ternary or a binary scenario. In fact, even if European culture is not considered binary by Lotman, the complete stop to almost every kind of economic activity and social relation and the slow re-opening reminds more of a binary system, thus justifying its description in apocalyptic terms. The presence of apocalyptic features and structures in opposed political discourses can be considered a hierophany, i.e. the re-emersion of the sacred in our ordinary, profane world23. In the absence of already encoded forms of content for the pandemic — a case of undercoding24 — political discourse brings back the ready-made traditional ones from religious discourse — a case of overcoding. For example, as we wrote above, in the Book of Revelation we find a connection between pandemic and economic crisis : the four Knights of the Apocalypse are identified with plague, famine, war and the antichrist. The source of the connection between epidemic, starvation and conflicts is prophetic literature, for example in Ezekiel (6, 11-12) : they are considered as a punishment for the sins and idolatry of the Jewish people. The concatenation gives meaning to these events. This peculiar structure can help the receiver of political discourse to cope with the absence of meaning involved by the spread of the virus and its absurd consequences, which we can consider as a case of accident in the perspective of the semiotics of interaction. In other terms, the apocalyptic framework reveals a moral sender behind the virus, allowing the reader to reinterpret the relation with the virus and finding a meaning in terms of political theology. But the Apocalypse is neither the only religious model borrowed by political discourse, nor the most common. Michael Walzer25 distinguishes three different political models: |

23 Cf. M. Eliade, The Sacred and the Profane : The Nature of Religion, New York, Harper Torchbooks, 1961. 24 U. Eco, A Theory of Semiotics, op. cit. 25 M. Walzer, Exodus and Revolution, New York, Basic Books, 1985. |

|

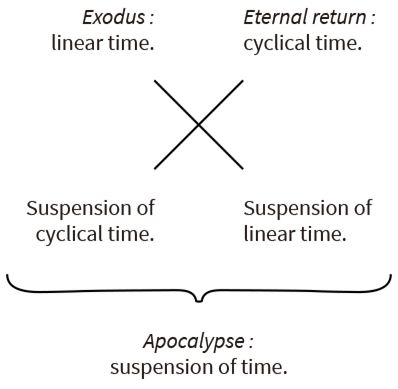

i) Eternal return : a mythical, cyclical cosmology in which terrestrial political models are justified as a mirror of the divine hierarchy. This model is obviously conservative ; ii) Exodus : an historical, linear model whose subject is the people, leaded by a non-charismatic authority. Walzer distinguishes among two different points of view on the “promised land”. From the point of view of the people, it represents a secular objective which can be reached through political struggle, while, from the point of view of the leaders (Moses and the Levites), it implies also to renew the people’s culture with the objective to abolish slavery and oppression. The real objective of the leaders is to abolish the difference between laity and clergy : they aim to form a people of clerics. Walzer’s reading of the exodus is heavily influenced by Lenin ; iii) Messianism : the kind of promised land is not a secular objective, set in a historical dimension : it is spiritual and disembodied. It is the promise of a renewal of humanity by God, or a return to Eden. Thus, the realization of promise is no more subordinated to a necessary political effort (in the case of the exodus, forty years in the desert, etc.). According to Walzer, while exodus is a politically realist model, millennialism is typical of radical political culture and explains its many failures. In his perspective, apocalypse represents the end of the history, and the advent of the perfect society. Furthermore, messianism waits for a charismatic leader, while exodus aims to organization : Moses, defined by Walzer as a good union representative, subdivides Jews in functional groups of thousand, hundred, fifty and finally ten men. On the contrary, charismatic messiahs represent the defeat of the political model shaped in the Exodus. However, if we look at the political speeches we analysed, we can see how the effectiveness of the apocalyptic model seems provided not by the messianic expectation of a charismatic leader, but rather by its character of suspension of time (Berardi: “Everything has stopped forever”). The crisis involves both a cyclical and a linear time : on the one hand, the cyclical time of capitalist economy and of the reproduction of capital (von der Leyen : “we have entered the worst recession since almost 100 years”), and, on the other hand, the linear time of progressive views on capitalism (Berardi : “We were continuing to believe in the possibilities of growth, expansion and so on”). In Appendix, fig. 2, we posit the temporal topology of the apocalypse as a neutral term : neither a circular nor a linear time. The neutral term has the function of rising above the considered ca- tegory, to declare its irrelevance or to neutralise it26 : our case seems particularly interesting, since the neutralised category is no less than that of temporality. According to the Italian historian and philosopher Furio Jesi, the suspension of historical time is usually functional to the adoption of extraordinary political means including the temporary suppression of the rule of law27. As a matter of fact, exceptional political instruments and “soft authoritarian” measures have been adopted in many countries besides Italy28. |

26 F. Marsciani, “Impertinenza e neutralizzazione”, in Minima semiotica, Udine, Mimesis, 2012, pp. 155-169. 27 F. Jesi, Spartakus : The Symbology of Revolt, Kolkata, Seagull Books, 2014. 28 On October 6th, 2020, the Italian Government prolonged the emergency state to January 30th, 2021. It is the first time in the history that this instrument of government has been extended to the whole national territory. Its use was previously limited to disaster areas. |

|

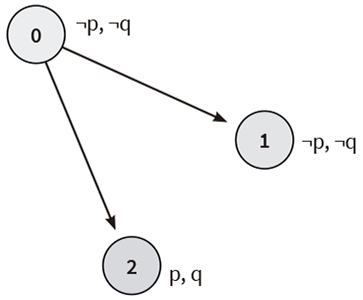

Apocalyptic references are not only functional to manipulation (the virus seen as a punishment for our sins). In fact, the function of apocalyptic literature is mainly consolatory. The Apocalypse and the texts that inspired it, such as the book of Daniel, are aimed at a minority persecuted because of the truth they profess. The Apocalypse is an optimistic book : Here we face the typical Christian paradox, according to which suffering is never seen as the last word but rather, as a transition towards happiness ; indeed, suffering itself is already mysteriously mingled with the joy that flows from hope.29 For this reason, the borrowing of apocalyptic structures by political discourse is functional to announce and justify a new programming phase. In van der Leyen’s speech this is the Next Generation EU programme, while in Berardi’s interview the new program is represented by “a form of life based on equality and frugality”. In both cases, we deal with a program based on a logical argument according to which we have access to only two possible futures30. In the first case, an euphoric outlook is related to an ethical reaction, while in the second one a dysphoric outcome is related to the presence of the same unethical behaviours which are linked to the pandemic in the present world (see Appendix, fig. 3). In this model, both q ? p and (p ? q) hold : in other terms, if we want a positive turn, then this implies a necessary change in our behaviour ; at the same time, a change of behaviour leads necessarily to a positive future. In van der Leyen’s speech, the ethical behaviour is represented by “a re-discovered sense of collective responsibility” and “public investments”, linked to “reforms”. In the euphoric future, European people will “drink clean water”, “breathe fresh air”, “see their children grow up in nature”, while the dysphoric one is represented as “increase flooding, heat waves, droughts and the loss of millions of species”. In Berardi’s interview, the ethical condition is a change of “expectations, behaviours, priorities”, while the euphoric outcome is represented by “a thousand intelligent communities, technologically hyper-gifted, emotionally affectionate, and capable of defending themselves by any means necessary”. In spite of the difference in the superficial interpretation of the crisis, the two speeches share the same immanent deterministic, mechanistic logic, which allows us to consider the sender of the political apocalyptic speech as a programming subject. Thus, the Apocalypse also has the function that Ferraro attributes to alpha-class architectures, at least from the point of view of the realisation of the enunciator. |

29 J. Ratzinger, “John, the Seer of Patmos”, http://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/ 30 I use the expression “possible future” as a particular case of possible word. Semiotics turned its attention toward the notion of possible world to integrate Greimas’s narrative model, which is intensional, with an extensional semantics, capable of locating narrative reference in a fictional world (see U. Eco, Lector in fabula, Milano, Bompiani, 1979). Ugo Volli criticised Eco’s point of view on possible worlds : the logical notion of possible world is a formal structure, whereas Eco’s possible world is material (see U. Volli, “Mondi possibili, logica, semiotica”, Versus, 19-20, 1978, pp. 123-148). Volli was undoubtedly right. However, I use a more formal notion of possible world that tries to link Greimas’s and Kripke’s notion of modality. However, there is a difference with Kripke’s semantics. While scholars in modal logic try to describe the different acceptations of modal operators in language, in my perspective, modal structures and models are specific to each text. See also F. Galofaro, “Presuppositional terms and Kripke semantics”, in A. Ga?kowski and M.W. Kopytowska (eds.), Current Perspectives in Semiotics : Signs, Signification, and Communication, Berlin, Peter Lang, 2018, vol. 1, pp. 135-154. |

|

The Apocalypse provides a model hardwired in western culture, linking meaning and political action in a teleological perspective, allowing decision makers to manage with the lack, in political language, of categories and schemas concerning the unforeseen. The apocalyptic reading seems allowed by an isomorphism between the structure of the narration in the Book of Revelation and the binary model of explosion described by Lotman. The Apocalypse is an empty structure ; each leader may freely fill in its formal positions with almost any actor. For example, according to one’s political position, the Antichrist may just as well be ideologically assimilated with fossil capitalism, Chinese communism, or simply the selfish behaviour of one’s own nation-state. Thus, political leaders appropriate the apocalyptic discourse to reshape or rebuild their identity in a period of crisis. More precisely, the teleological explanation of pandemic as an opportunity acts on different levels : broadly at the level of meaning-making (why does God allow his worshippers to suffer ?) and more specifically at both the pathemic (hope for social change) and moral (final battle against evil forces) levels. In comparison to Lotman’s notion of “explosion”, Landowski’s regimes of interaction represent a more morphodynamic model. After the apparent absurdity of the break corresponding to the pandemic, the apocalyptic reading provides an eschatological meaning to it, dignifying in a moral sense the suffering and the reaction of the people in terms of efforts to recover lost grounds31. As we wrote above, the apocalyptic model foresees that a change of behaviour leads necessarily to an utopian future, to the perfect society and to the end of the history. Thus, the apocalyptic logic justifies in moral terms the opening of a new programming phase. |

31 A moral reading of pandemics characterises many literary representations both in ancient and in contemporary times. However, a peculiarity of contemporary literature is the absence of a moral sender. Cf. J. Ponzo, “L’epidemia nell’immaginario letterario italiano degli anni ’80 : Cerami e Angelini”, communication to the XLVIII symposium of the Italian Association for Semiotics (AISS) (October 2020) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=61MpKh8_mK8 |

|

If semiotics aspires to become a general theory of culture, it cannot be content with the simplistic proposal of another philosophy of history among others. In the history of culture, we meet many syntagmatic philosophies of history, interpretations aimed at providing a meaning to a merely factual series of stochastic events. These theories select an iterative phenomenological trait of political experience and use it as a constant selected by other features, considered as variables. For example, according to Plato’s political circle, each form of government degenerates, thus creating the premises for change : monarchy (tyranny) — aristocracy (oligarchy) — democracy (demagogy). These theories can be considered as transformational algorithms32. On the opposite side, paradigmatic philosophies (e.g. Marxism) propose dialectic algorithms regulating the transformation of values on a system33. But algorithms express only a fixed order of changes (they are programmed relations, both in Greimas’s and Landowski’s sense). If we consider syntagmatic transformation and paradigmatic dialectics as two distinct dimensions of a matrix, we can still think of a comprehensive theory of culture capable of understanding the stabilisation or the becoming unstable of matrices. From our point of view, the trajectory accident-adjustment in Landowski’s schema represents an advancement in this direction. In fact, the adoption of the apocalyptic logic described above implies a risk : fighting the pandemic with a programming strategy seems a quite rigid, mechanistic answer. Being a biological entity, the virus does not necessarily adhere to our schedules : its behaviour is not deterministically predictable. Furthermore, unlike the promised land of the exodus, the new world of the apocalypse does not imply engagement and struggle. Some consequences are visible in Italy, where the three phases foreseen by the program of the government to oppose the virus dramatically failed : the reopening of the touristic sector during summer and of public services such as the schools allowed the return of the virus, and the rigidity of the political priorities of the government caused a tragic delay in the reaction, and 16.750 deaths in November. |

32 Cf. A.J. Greimas and J. Courtés, op. cit., p. 11. 33 Ibid. |

|

The rigidity of the programmed strategies is reinforced by the binary opposition between good and evil forces figurativised by the “Armageddon”, precluding the possibility of tactics34 and agreements. Probably, as Landowski suggests, a more flexible approach based on local policies of adjustment between the spread of the virus and the specific characteristics of the population would be more advisable35. Unfortunately, at the moment this is an improbable scenario, not only because of the emergency of the current situation but also because of the elephantine slowness of so many bureaucratic procedures designed to safeguard partisan interests. |

34 On the opposition between strategy and tactics, see M. De Certeau, L’invention du quotidien 1: arts de faire, Paris, Gallimard, 1990, pp. 125-134. 35 “Face à pandemia”, Acta Semiotica, 1, 2020. |

|

References BJ, La Bible de Jérusalem, Paris, Cerf, 3rd ed., 1998. De Certeau, Michel, L’invention du quotidien 1 : arts de faire, Paris, Gallimard, 1990. Demuru, Paolo, “Between Accidents and Explosions : Indeterminacy and Aesthesia in the Becoming of History”, Bakhtiniana, 15, 1, 2020. — “Caos, teorias da conspiração e pandemia”, Acta Semiotica, 1, 2021. Eco, Umberto, A Theory of Semiotics, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1976. — Lector in fabula, Milano, Bompiani, 1979. — Semiotics and the Philosophy of language, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1986. Eliade, Mircea, The Sacred and the Profane : The Nature of Religion, New York, Harper Torchbooks, 1961. Ferraro, Guido, Semiotica 3.0 : 50 idee chiave per un rilancio della scienza della significazione, Roma, Aracne, 2019. — “L’accidente e il sistema. Forme di narrazione dell’epidemia”, Acta Semiotica, 1, 2021. Galofaro, Francesco, “Presuppositional terms and Kripke semantics”, in Artur Ga?kowski and Monika Weronika Kopytowska (eds.), Current Perspectives in Semiotics : Signs, Signification, and Communication, Berlin, Peter Lang, 2018, vol. 1. Girardi, Giulio, Marxismo e cristianesimo, Assisi, Cittadella, 1972. Greimas, Algirdas J. and Joseph Courtés, Semiotics And Language : An Analytical Dictionary, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1982. Idone Cassone, Vincenzo, Bruno Surace and Mattia Thibault (eds.), I discorsi della fine. Catastrofi, disastri, apocalissi, Roma, Aracne, 2018. Jesi, Furio, Spartakus : The Symbology of Revolt, Kolkata, Seagull Books, 2014. Landowski, Eric, Rischiare nelle interazioni (2005), Milano, FrancoAngeli, 2010. — “Face à pandemia”, Acta Semiotica, 1, 2021. Lenin, Vladimir Ilich, Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism, London, Penguin Classics, 2010. Lotman, Juri, Culture and Explosion, Berlin, De Gruyter, 2009. |

|

|

Marsciani, Francesco, “Impertinenza e neutralizzazione”, in Minima semiotica, Udine, Mimesis, 2012. Panier, Louis, “Des figures dans les récits : La guérison de la femme courbée in Lc 13, 10-17”, in Camille Focant and André Wénin (eds.), Analyse narrative et bible, Leuven, Leuven University Press, 2005. Petitimbert, Jean-Paul, “Anthropocenic Park : ‘humans and non-humans’ in socio-semiotic interaction”, Actes Sémiotiques, 120, 2017. Ponzo, Jenny “L’epidemia nell’immaginario letterario italiano degli anni ’80 : Cerami e Angelini”, 2020 AISS XLVIII symposium, Future past, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=61MpKh8_mK8&list=PLSTiiR_8LfDIdplELq8hEj-fskFOAz_oH&index=5&t=12s&ab_channel=AssociazioneItalianaStudiSemiotici. Ratzinger, Joseph, “John, the Seer of Patmos”, http://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/audiences/2006/documents/hf_ben-xvi_aud_20060823.html. Volli, Ugo, “Mondi possibili, logica, semiotica”, Versus, 19-20, 1978. Walzer, Michael, Exodus and Revolution, New York, Basic Books, 1985. |

|

|

Appendix

Fig. 1. Landowski’s regimes of interaction and meaning (Source : P. Demuru, |

|

Fig. 2. Temporal topology of theological-political models.

Fig. 3. The internal logic of the political apocalyptic arguments. In the present world 0, an unethical behaviour (¬p) is related to a dysphoric condition such as pandemic and economic crisis (¬q). According to the apocalyptic logic, there are only two possible futures we can access : in the future world 1, the unethical behaviour and the dysphoric condition persist, while in the future world 2 an ethical behaviour (p) is adopted, leading to a euphoric condition (q). In this scenario, q ? p and (p ? q) hold. Graphic generated with modal logic playground (http://rkirsling.github.com/modallogic/?model=AS1,2;AS;Ap,qS;;). |

|

* This article is part of the research project NeMoSanctI (New Models of Sanctity in Italy (1960s-2000s) A Semiotic Analysis of Norms, Causes of Saints, Hagiography, and Narratives), which has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 757314). 1 Regarding translation, critical apparatus and the reconstruction of the historical background, we base on La Bible de Jérusalem, Paris, Cerf, 1998 (3rd ed.). 2 U. Eco, A Theory of Semiotics, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1976. 3 Cf. Les interactions risquées, Limoges, Pulim, 2005. Landowski’s model inter-defines four regimes of interaction, meaning, and risk : programming, manipulation, adjustment, and accident (see Appendix, fig. 1). It also defines the syntagmatic relations linking these regimes, thereby allowing to outline various trajectories of transformation. On this dynamic aspect, see for example J.-P. Petitimbert, “Anthropocenic Park : ‘humans and non-humans’ in socio-semiotic interaction”, Actes Sémiotiques, 120, 2017. 4 J. Lotman, Culture and Explosion, Berlin, New York, De Gruyter, 2009. 5 On the wide presence of apocalyptic discourses in contemporary media cf. V. Idone Cassone, B. Surace, M. Thibault (eds.), I discorsi della fine. Catastrofi, disastri, apocalissi, Roma, Aracne, 2018. 6 https://www.legambiente.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Linquinamento-atmosferico-al-tempo-del-Coronavirus.pdf 7 U. Eco, Semiotics and the Philosophy of language, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1986, p. 158. 8 L. Panier, « Des figures dans les récits : La guérison de la femme courbée in Lc 13, 10-17 », in Camille Focant and André Wénin (eds.), Analyse narrative et bible, Leuven, Leuven University Press, 2005, pp. 425-430. 9 U. Eco, Semiotics and the Philosophy of language, op. cit., p. 146. 10Discursive configurations are “micro-narratives with an autonomous syntactic/semantic structure, which can be integrated in larger discursive units and acquire thereby functional significations corresponding to their positions in these larger units”. A.J. Greimas and J. Courtés, Semiotics And Language : An Analytical Dictionary, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1982, p. 49. 11G. Ferraro, Semiotica 3.0 : 50 idee chiave per un rilancio della scienza della significazione, Roma, Aracne, 2019, pp. 93-138. See also, in the present volume, G. Ferraro, “L’accidente e il sistema. Forme di narrazione dell’epidemia”. 12 In his contribution to the present issue, Paolo Demuru recognises two isotopies connected to the apocalypse : the prophetic announcement of pain and the salvific value. According to our analysis, there is a third value : the revelation of the truth. 13 Cf. V.I. Lenin, Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism, London, Penguin Classics, 2010. 14Interview published by the online magazine fanpage.it : https://www.fanpage.it/cultura/il-diario-del-lockdown-di-bifo-svegliatevi-ragazzi-lapocalisse-e-in-corso/. Despite the imminent apocalypse, Berardi promotes his new book, a diary of the lockdown. 15 Cf. G. Girardi, Marxismo e cristianesimo, Assisi, Cittadella, 1976, pp. 36-37. 17 About “the pillars of the New Europe”, cf. https://ec.europa.eu/info/live-work-travel-eu/health/coronavirus-response/recovery-plan-europe/pillars-next-generation-eu_en. 18 P. Demuru, “Between Accidents and Explosions : Indeterminacy and Aesthesia in the Becoming of History”, Bakhtiniana 15, 1, 2020, p. 85. 19J. Lotman, Culture and Explosion, op. cit., pp. 17-18. 20 Ibid, p. 172. 21 Ibid, p. 173. 22 Ibid. 23 Cf. M. Eliade, The Sacred and the Profane : The Nature of Religion, New York, Harper Torchbooks, 1961. 24 U. Eco, A Theory of Semiotics, op. cit. 25 M. Walzer, Exodus and Revolution, New York, Basic Books, 1985. 26 F. Marsciani, “Impertinenza e neutralizzazione”, in Minima semiotica, Udine, Mimesis, 2012, pp. 155-169. 27 F. Jesi, Spartakus : The Symbology of Revolt, Kolkata, Seagull Books, 2014. 28 On October 6th, 2020, the Italian Government prolonged the emergency state to January 30th, 2021. It is the first time in the history that this instrument of government has been extended to the whole national territory. Its use was previously limited to disaster areas. 29 J. Ratzinger, “John, the Seer of Patmos”, http://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/audiences/2006/documents/hf_ben-xvi_aud_20060823.html. 30 I use the expression “possible future” as a particular case of possible word. Semiotics turned its attention toward the notion of possible world to integrate Greimas’s narrative model, which is intensional, with an extensional semantics, capable of locating narrative reference in a fictional world (see U. Eco, Lector in fabula, Milano, Bompiani, 1979). Ugo Volli criticised Eco’s point of view on possible worlds : the logical notion of possible world is a formal structure, whereas Eco’s possible world is material (see U. Volli, “Mondi possibili, logica, semiotica”, Versus, 19-20, 1978, pp. 123-148). Volli was undoubtedly right. However, I use a more formal notion of possible world that tries to link Greimas’s and Kripke’s notion of modality. However, there is a difference with Kripke’s semantics. While scholars in modal logic try to describe the different acceptations of modal operators in language, in my perspective, modal structures and models are specific to each text. See also F. Galofaro, “Presuppositional terms and Kripke semantics”, in A. Ga?kowski and M.W. Kopytowska (eds.), Current Perspectives in Semiotics : Signs, Signification, and Communication, Berlin, Peter Lang, 2018, vol. 1, pp. 135-154. 31 A moral reading of pandemics characterises many literary representations both in ancient and in contemporary times. However, a peculiarity of contemporary literature is the absence of a moral sender. Cf. J. Ponzo, “L’epidemia nell’immaginario letterario italiano degli anni ’80 : Cerami e Angelini”, communication to the XLVIII symposium of the Italian Association for Semiotics (AISS) (October 2020) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=61MpKh8_mK8&list=PLSTiiR_8LfDIdplELq8hEj-fskFOAz_oH&index=5&t=12s&ab_channel=AssociazioneItalianaStudiSemiotici. 32 Cf. A.J. Greimas and J. Courtés, op. cit., p. 11. 33 Ibid. 34 On the opposition between strategy and tactics, see M. De Certeau, L’invention du quotidien 1: arts de faire, Paris, Gallimard, 1990, pp. 125-134. 35 “Face à pandemia”, Acta Semiotica, 1, 2020. |

|

______________ Keywords : accident, explosion, interaction, pandemic, political discourse, religion, possible worlds, political theology Mots clefs : accident, discours politique, explosion, interaction, mondes possibles, pandémie, religion, théologie politique. Authors quoted : Michel de Certeau, Paolo Demuru, Umberto Eco, Mircea Eliade, Guido Ferraro, Algirdas J. Greimas, Furio Jesi, Eric Landowski, Juri Lotman, Louis Panier, Jenny Ponzo, Ugo Volli, Michael Walzer. Plan : 2. Prophecy in two opposite political discourses |

|

Pour citer ce document, choisir le format de citation : APA / ABNT / Vancouver |

|